Resiliency Corner by Haley & Aldrich—Points of Strength: Resilience Hub in Chiloquin

by Lucy Bishop, Daniele Spirandelli, and Sarah Sieloff, Haley & Aldreich

Chiloquin, Oregon is a city of 790 residents in south central Oregon. A former timber town, Chiloquin made history in 1926 as the first city incorporated on a Native American reservation. (1) It is small, isolated, vulnerable, and on the brink of something big. With over $17 million in funding support since 2021, Chiloquin is poised to start designing and building a new community resilience center. How it got here is a story that can inform small, rural communities striving to improve their own resilience in the face of economic and climate uncertainty.

What is a resilience hub, and why does it matter?

A resilience hub is a facility that is known locally and provides resources in both disaster recovery situations and day-to-day life. “It is a facility that is really trusted...for resources in both blue (daily) and gray sky (disaster) situations,” says resilience expert Cuong Tran, a contractor with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office for Coastal Management (NOAA) in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi who completed his urban planning master's research on resilience hubs. “[Resilience hubs] are not a new thing”, Tran explains. “The term ‘resilience hub’ is recent. In Hawaiʻi, it began after Hurricane Maria in 2017, when Puerto Rico was hit and the residents formed impromptu resilience hubs during disaster recovery.”

Hurricane Maria destroyed much of Puerto Rico, leaving the island in an isolation phase without electricity for 11 months and generating an estimated $139 million in property and economic losses. These resilience hubs offered food, water, first aid, phone charging, and other basic services even as destroyed coastal infrastructure left aid shipments waiting in harbors. Hurricane Maria demonstrated the need for community-informed resilience hubs, particularly in geographically isolated communities.

Community resilience, according to the Urban Sustainability Director’s Network (USDN), is the ability to anticipate, accommodate, and positively adapt to or thrive amidst changing climate conditions, while enhancing quality of life, reliable systems, economic vitality, and conservation of resources. It requires community capacity to plan for, respond to, and recover from stressors and shocks. This can be difficult to build particularly among small, geographically isolated, low-income or low-capacity municipalities; for instance, many rural communities near Asheville, North Carolina faced significant challenges in recovering from Tropical Storm Helene in 2024, including lack of road access, which prolonged the recovery process. For these disadvantaged communities, resilience hubs are proving indispensable for building this community resilience by serving as a central point for creating strategies to address community vulnerabilities, foster preparedness, and work with trusted leaders to strengthen community bonds before disruptions occur (according to USDN). This work allows the hubs to not only deliver immediate disaster relief but also cultivates social cohesion and quickens the road to recovery while mitigating disaster-associated economic losses.

The exact function of any given resilience hub varies based on a community's strengths, needs and goals. Resilience hubs have multiple functions and command three key types of assets: physical, social, and human. Physical assets are specific facilities and material resources in a community, like “medical facilities; community facilities such as libraries and schools; and public facilities such as police stations, fire stations, and hospitals,” notes Tran. As a physical asset, resilience hubs provide services, resources, and connection on a daily basis, while also activating in times of crisis. Social assets are formal or informal trusted relationships within a community. Examples, says Tran, could be emergency managers, government agencies, and private businesses. Human assets are the skills, talents, and knowledge that residents and individuals in the community share. Examples, Tran cites, include skills like “fishing, financial management, or disaster preparedness.”

In his research, Tran compared physical, social, and human assets in rural and urban communities and ranked them by relative importance. According to Tran, it’s perhaps not surprising that “rural communities ranked social assets above human and physical assets compared to their urban counterparts…in rural communities, there are fewer physical assets; however, you are more in touch with your fellow residents.” This strong social capital provides a unique advantage in establishing resilience hubs in rural communities, as existing connections prime residents to collaborate more easily on resilience preparedness and response. Tran also notes the role of community champions who represent local interests in resilience hub planning: “They represent the voice of the community and meet with local government agencies and other partners to help establish the resilience hub.” These individuals are particularly crucial in rural areas because they can leverage existing social capital to effectively engage residents and facilitate collaboration to advance resilience efforts.

Resilience hubs in action

The aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico in 2017 inspired several Hawaiʻian communities to strengthen disaster preparedness capabilities by organizing their own resilience hubs. These hubs were the subject of Tran’s research.

The small, rural community of Koʻolauloa, on Oahu’s North Shore, offers an example. Koʻolauloa has been identified as one of the most climate change-vulnerable communities in Hawaiʻi and its accessibility to the rest of the island relies solely on the Kamehameha Highway, meaning it could have limited access to help in an emergency. While Koʻolauloa is geographically vulnerable, it is compensating for this weakness through its strong human and social assets. Residents are identifying collective skills and knowledge, expanding their social networks, and enhancing social cohesion, which all builds community resilience. This community growth has led to residents collaboratively managing Hawaiʻi’s first community-informed resilience hub.

The concept of a community resilience hub in Koʻolauloa emerged from extensive community planning, emergency preparedness training, and workshops led by the non-profit Hui O Hauʻula with support from federal, state, and county grants. With only a single road in and out, Koʻolauloa could have limited access to help in an emergency, and it has promoted community resilience by leveraging strong human and social assets. This includes expanding social networks and identifying neighbors' skills and knowledge. Koʻolauloa has capitalized on this by securing grant funding that will bring the design of a resilience hub to fruition. The resilience hub, set for completion in 2027, will include community education and training, emergency shelter, locally grown food, and medical services. Its ultimate goal is to allow Koʻolauloa to be self-sustaining during the critical time immediately after an emergency.

Tran stresses that a question at the core of resilience planning is definitional. Some federal and state agencies define resilience as “the ability of a community to bounce back after a hazardous event” (NOAA, 2020). Researchers have critiqued this definition as short-sighted and incorrectly focused on hard infrastructure solutions that attempt to control nature, rather than on holistic options that work with nature, center human needs, and shift decision-making power into neighborhoods.

Chiloquin’s Story

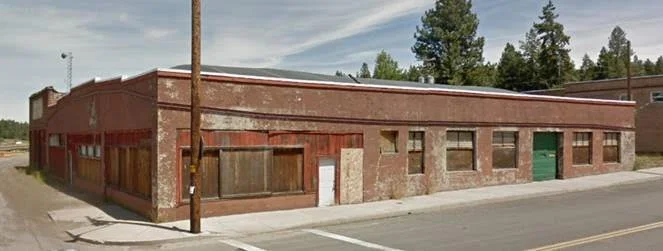

Chiloquin’s resilience story doesn’t start with a resilience hub – it starts with dilapidated, contaminated buildings. In a city with a downtown of half a block by half a block, large brick structures like the Chiloquin Mercantile Building and the former Markwardt Brothers Garage figured prominently, and both were in bad shape. Special Projects Director Cathy Stuhr recalls that downtown Chiloquin used to be a “major intersection of gravel lots and boarded up buildings.”

Original Markwardt building before its collapse

Chiloquin sought grants to support a redevelopment effort, beginning with a $300,000 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Brownfields Community-wide Assessment Grant in 2021,a $402,500 EPA Brownfields Cleanup Grant in 2022, and in 2023, secured $200,000 from Business Oregon and $125,000 from regional foundations. Identified contamination included petroleum, abandoned underground storage tanks, asbestos-containing materials, lead-based paint, and lead in soil within 200 feet of homes. Then, in 2021, the Chiloquin Mercantile Building partially collapsed and was demolished due to safety reasons in 2024.

The Markwardt building collapsed

In total, between 2021 and 2024, Chiloquin leveraged over $1 million in state, federal and philanthropic contributions to support environmental investigation, cleanup, and reuse planning for its largest downtown brownfields sites.

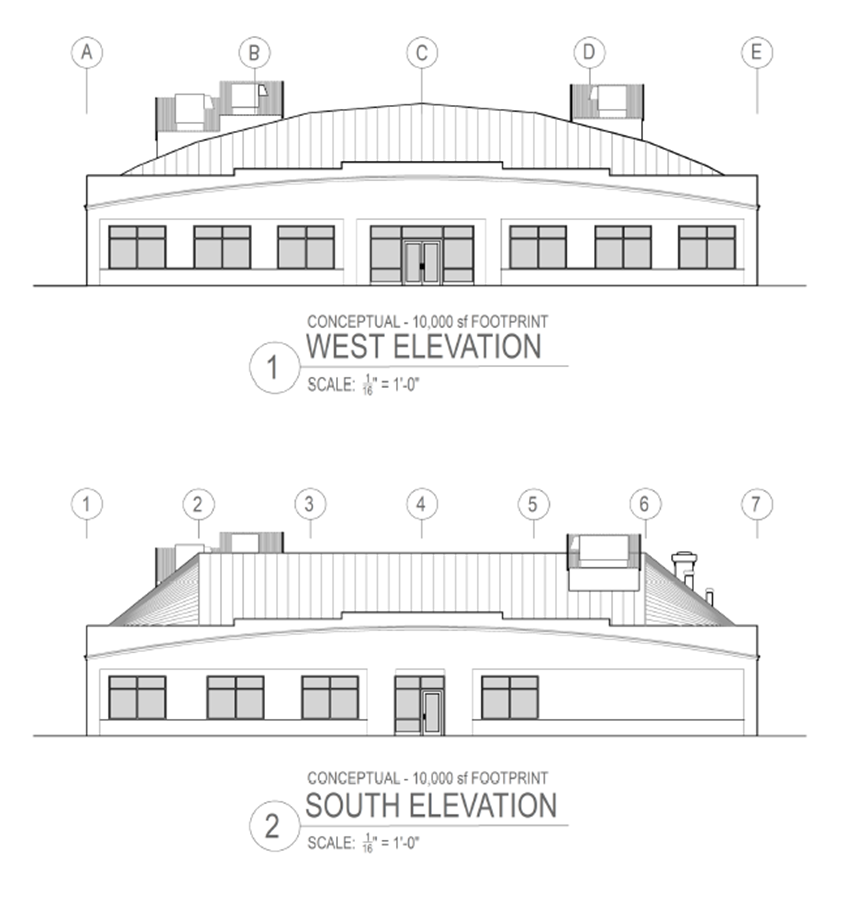

Future site for the Resilience Hub

At the same time, the world around Chiloquin was increasingly on fire. In September 2020, The Two Four Two Fire burned for more than two weeks northwest of Chiloquin, destroying eight homes and forcing 482 people to evacuate. In 2024, The Copperfield Fire burned over 3,822 acres, destroying eight homes and 22 other structures. In Chiloquin, the local emergency response was disorganized. “The community didn’t know where to go,” explains Stuhr. “During the Two Four Two Fire, everyone ended up in the casino parking lot, which was cold and confusing. The Copperfield Fire split people up, then multiple government agencies issued simultaneous evacuation instructions, making matters even more confusing.” Given the increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires, the City recognized it was only a matter of time until the next fire. They needed a different approach.

In 2024, the City applied for an EPA Community Change Grant. This one-time program, funded by the 2021 Inflation Reduction Act, made available $2 billion to support initiatives at the intersection of climate change and environmental justice. Chiloquin developed a grant proposal that leveraged its past brownfields redevelopment activity to support a municipal center and resilience hub.

Floor plan for the Resilience Hub

The application development process was far from streamlined. Initial partnerships fell through, and the project area shifted. Each time, Chiloquin adapted. The City’s grant application told a story of brownfield redevelopment through an environmental justice lens. The City faces serious health threats from poor air quality, a major source of which are home fireplaces. Wood is the cheapest fuel available for winter heating, and many fireplaces are old and do not meet current air quality standards.

Smoke from increased climate change-driven wildfires adds an additional environmental burden that threatens residents’ health. The demographic and socioeconomic profile of Chiloquin’s population means many residents are particularly vulnerable to these burdens: 63% of Chiloquin residents are Native American, 36% are over age 65 (versus 16.5% on average in the US), and 39% are low income. The intensity of climate-related threats will only increase.

Elevation drawing of the building

All this means disability and chronic illness both disproportionately impact Chiloquin residents. The resilience hub will offer Chiloquin’s most vulnerable populations—like seniors, medically fragile people, and families with small children— a safe place to shelter regardless of income and access to resources, and without having to leave town. It will also host a wood stove trade-in program, so that families whose wood-burning stoves do not meet EPA standards can receive a new one that contributes to improved indoor and outdoor air quality in Chiloquin and the broader region. Finally, City Hall will be co-located with the resilience hub, allowing staff to occupy a healthier building.

Importantly, as part of planning and developing its resilience center, Chiloquin will consider how to most effectively link the new resilience hub with two existing local facilities whose assets are part of resilience plans. These include a Tribal community fitness center and a building with a commercial kitchen from which emergency food could be prepared and dispatched.

Community input will drive the resilience hub’s design and programming, and it will serve as a community gathering space and offer training and capacity building for residents. This will help reduce risks from climate-related disruptions by building social cohesion and community capital. Because people will know what resources exist and how to use them, the City’s ability to respond to disasters and emergencies will improve.

Building on assets

Especially for small, rural, isolated, and underserved municipalities, community resilience is a critical but often overlooked aspect of disaster preparedness. By definition, disasters generate unexpected consequences, but the act of organizing a community resilience hub requires focus, and that can vastly improve a small community’s ability to not only weather a disaster but emerge with momentum and a clear vision for moving forward.

Chiloquin’s experience illustrates the importance of using an asset-based approach to assess needs and opportunities for a resilience hub. This includes understanding what resources exist, including non-physical assets like community strengths, knowledge, skills and partnerships. It also requires understanding where gaps exist and developing a funding strategy in response.

Perhaps most critical to any resilience project is a champion and leader like Cathy Stuhr in Chiloquin, and a commitment to capacity building. Enhancing local capacity to plan for and weather an unexpected event is an outcome of the planning process, and an outcome of the function of the resilience center.

The Trump Administration’s shift away from climate resilience and environmental justice-focused policy has generated uncertainty about the future of associated funding. Nevertheless, Chiloquin is moving ahead with beginning the process of implementing its Community Change Grant and is strengthening state and philanthropic partnerships to sustain the resilience hub long-term. “The sky’s the limit,” exclaims Stuhr. “There’s so much happening, and we’ve got the right people in the right place – hopefully, the funding will follow.”

References

(1) Chiloquin was incorporated on the historic homelands of the Klamath Tribe, which were incorporated into US National Forest Lands when Congress terminated federal recognition in 1954. After years of advocacy, the Klamath Tribe regained federal recognition in 1986, but their lands were not returned. (See https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/klamath-indian-reservation/ and https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/klamath-tribal-council-1955/).

About the Authors

Lucy Bishop is a Senior Techincal Expert, Environmental Scientist at Haley & Aldrich. She leads the in situ community of practice there, leveraging her extensive experience as an environmental consultant and contractor to navigate the complexities of subsurface remediation. Having implemented hundreds of in situ remedies, she combines scientific expertise in environmental chemistry and engineering with a practical understanding of real-world challenges. Elizabeth takes a strategic, goal-oriented approach, working closely with clients to align remediation plans with project objectives while adapting to evolving conditions for efficient execution.

Daniele Spirandelli is a Senior Associate, Climate Resilience Specialist with Haley & Aldrich. She is a systems-oriented resilience planner who collaborates with diverse clients and stakeholders to address climate change challenges. With over a decade of experience, she integrates climate science, adaptation strategies, and community perspectives to develop holistic resilience solutions. She has worked with communities and institutions across the Pacific Northwest and Hawaii, including utility companies, real estate developers, and county planners. As a member of ASTM International’s subcommittee on property resilience assessments, Daniele applies scientific tools, traditional ecological knowledge, and collaborative approaches to co-produce knowledge and prioritize sustainable solutions.

Sarah Sieloff is a Technical Expert with Haley & Aldrich. Sarah has dedicated her career to helping public and private sector clients navigate rapidly evolving issues like environmental justice, climate resilience, and state and federal funding. Her expertise includes grants and funding, public policy research and analysis, intergovernmental relations, and brownfield redevelopment. She served as a 2020 Council on Foreign Relations-Hitachi fellow in Japan and the executive director of the nonprofit Center for Creative Land Recycling. Sarah also spent nearly four years in federal service, including two as the Memphis, Tennessee, team lead for the White House Council on Strong Cities, Strong Communities. Sarah has a passion for helping communities build more sustainable, livable futures.

Information on Those Interviewed

Cuong Tran is a Resilience Specialist with Tellus Civic Service on contract with the NOAA Office for Coastal Management. He has a background in data science, community outreach, coastal management, and disaster preparedness and recovery. Cuong was raised in Lahaina, Maui, where he developed a lifelong passion for serving the people of Hawai'i and the Pacific.

Cathy Stuhr has more than 30 years’ experience managing multimillion-dollar brownfield environmental assessment, investigation, and remediation projects with significant community and public involvement components. As a contractor to USEPA Region 9, she served as a national expert in the USEPA Hazard Ranking System (Superfund). Ms. Stuhr is currently the project manager for the City of Chiloquin’s Brownfield Assessment and Cleanup grants. She has an MBA from Golden Gate University and a B.S. in Environmental Policy Analysis and Planning, from the University of California, Davis.

About Resiliency Corner

Resiliency Corner is brought to our Western Planner readers by Haley & Aldrich. Haley & Aldrich’s nationwide team of environmental and geotechnical engineering consultants build on a heritage of acting on the specific needs of our clients through advocacy, technical excellence, and innovation. Learn more at https://www.haleyaldrich.com/