Is it Time For a Tune-up? A Standard Operating Procedure for Code Maintenance

By Scot Siegel, FAICP

Introduction

Home builders, developers, real estate professionals, and others frequently blame complicated or ambiguous development regulations for delays in permitting, housing shortages, business disinvestment, and other community issues. High-functioning planning departments know this and proactively maintain their jurisdiction’s codes, standards, and procedures. “Code Maintenance” can also be a strategy for advancing a wide range of policy priorities, such as maintaining a high level of customer service. Think of your code as a piece of critical equipment, like a computer or car. Without routine maintenance, such as updates to an operating system, or an oil change, that machine slows down and may eventually die.

Why?

In addition to drafting ordinances to implement local plans, planners must respond to changes in the legal landscape, shifting policy priorities, new building technology and planning best practices, among other issues. Changes in law, including legislation, case law, and new administrative rules adopted by state and federal agencies, can drive the need for code maintenance. Additionally, planners must maintain and update codes to be consistent with new policies resulting from local planning initiatives. Oftentimes, conflicting code language results from amending one section of code without reviewing and updating other related regulations. Poor or inconsistent organization, formatting, syntax, and writing style can also contribute to permitting delays and errors in code administration

Code maintenance includes correcting and clarifying regulations to make them more readable, resulting in a more efficient permit process while complying with the law. From a community development perspective, maintenance amendments can improve coordination between different functional areas of local government, such as planning, building safety, engineering, public safety, and public works operations, with a focus on positive community outcomes. For example, by reconciling conflicts between land use regulations, engineering standards (streets, sidewalks, utilities, surface water, etc.), and building codes, code maintenance can help streamline the permit process and improve customer service.

Types of Code Maintenance

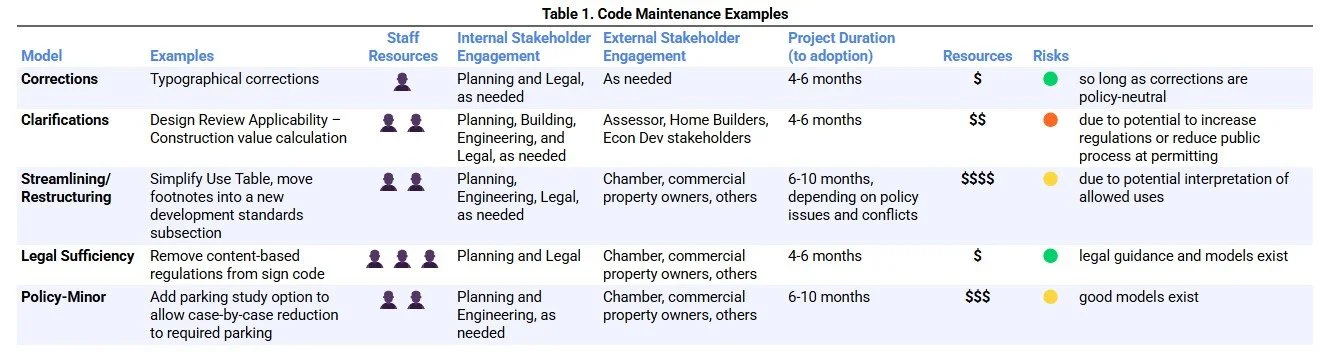

For purposes of this article, we examine five types of code maintenance amendments: Corrections, Clarifications, Restructuring, Compliance, and “Minor Policy” changes. Planners can use the following rubric and examples to help discern the type of code maintenance that is needed, or whether a code amendment would not be considered maintenance because it is a major policy change.

1 ) Corrections

Scrivener’s errors

Typographical errors

Syntax

Cross references, ordinance citations, etc.

2) Clarifications

Codification (assembling multiple ordinances not already codified)

Interpretations

Other clarifications

Definitions

3 ) Restructuring/Streamlining

New code drafting conventions (e.g., applying state law directly with cross-referencing, or incorporating state requirements into local code)

Unification/Relocation (e.g., consolidating allowed uses, standards, or permitting procedures into stand-alone sections)

4) Legal Sufficiency

Federal laws and rules (most common)

Constitutional issues

First Amendment (Speech, Fair Housing, etc.)

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments (Takings)

Code of Federal Regulations, agency rules (e.g., FEMA requirements for development in flood hazard areas)

State laws and rules

Statutes and agency administrative rules

Case law

5) Minor Policy. Code amendments implementing minor policy changes may be considered maintenance, provided the changes are grounded in existing plans or policy direction from the governing body, planning commission, or other advisory body.

Table 1 below provides examples of the above types of code maintenance amendments.

Drawing the line between Maintenance and Major Policy Change

Major policy changes are not “maintenance”. However, maintenance may include minor policy changes, as discussed above. These amendments are typically narrow in scope and easily addressed with existing staff resources. Minor policy amendments require minimal investment of stakeholders’ time – they do not require standing up a new ad hoc committee, for example. They are also typically guided by existing adopted city plans, state or federal mandates, governing body goals, or committee recommendations.

Project Management

As with other planning projects, establish a project team (project manager, task leaders, reviewers, etc.) and a clear scope of work linked to specific goals and outcomes. You will want to consult subject matter experts, including staff from other departments, as appropriate, to ensure their operational needs are being met. The scope of work should consist of a work plan, schedule, and budget, with assigned personnel, funding, and the procurement of any outside services, as needed. Many types of project management tools can be used. The most essential are those that facilitate communication, track project tasks, deliverables, and timelines, and ensure quality control.

About the Author

Scot Siegel, FAICP is a highly accomplished community development leader with over 30 years of experience in urban planning, policy development, and organizational management across both the public and private sectors. With a deep expertise in strategic planning, economic development, and affordable housing, Scot has successfully directed major projects and initiatives aimed at improving community infrastructure, fostering equity, and empowering local residents. He is currently the Community Development Director of Newberg, Oregon. Scot has also held senior leadership positions in various municipalities, including serving as Community Development Director for the City of Lake Oswego and Director of Land Use Planning for Multnomah County. He holds a Bachelors of Science in Geography from Oregon State University and a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from Portland State University.