View From Above: Plan Your Flight and Fly Your Plan

by Ari Johnson

This article was originally published in the NDPA newsletter and is reprinted with permission from the North Dakota Planning Association. Visit www.ndplanning.org to learn more.

NDPA Editors’ notes: The following article was provided by Ari Johnson, a lawyer from Watford City and regular presenter at NDPA Annual Conferences. Ari’s documentation as an amateur pilot demonstrates the importance of land use planning and zoning near airports and provides a first-hand experience of the importance of safe and navigable airports across North Dakota. There are 8 commercial service airports located in North Dakota and 81 general aviation public airports. According to the North Dakota Aeronautics Commission (NDAC), over 80% of the rural public airports do not have height zoning as recommended by Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 77 and none of the grass runway airports that Ari visited have these protections.

North Dakota has something for everyone. For pilots, the North Dakota Aeronautics Commission has the Passport Program, which recognizes those who land at all 89 of the state’s public-use airports. The prize is the task itself: seeing all of North Dakota from the air. The token of recognition is a leather jacket (along with a hat and a flight bag for the first 30 and 60 airports visited, respectively). When I put that 89th and final stamp in my passport book, I will not be the first, by any stretch of the imagination. The Aeronautics Commission lists no fewer than 58 pilots who beat me to the punch, some from as far away as Washington, Georgia, and Texas.

There are a handful of airports across the state without a paved runway, and I decided to spend a couple of days in the summer of 2019 visiting most of them in my dad’s beautifully restored 1941 Piper J-3 “Cub” airplane. The Cub is ideal for visiting quaint grass landing strips and seeing the whole state from the air. It is uncomplicated, unburdened by modern electronics, and gives a “low and slow” view of the world below.

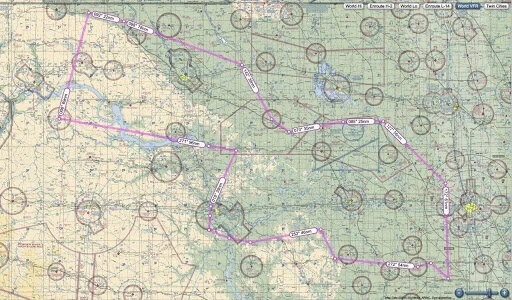

The planning phase of my trip would provide enough material for its own article, although it would be interesting mostly to other pilots. In short, I planned this trip years in advance and, when the statewide weather was right, all I had to do was get in the plane and go. I landed at 12 airports on Saturday, July 20, slept on a couch at the airport in Kulm—I brought a tent but, in the end, I chose air conditioning over mosquitoes—and landed at another 6 airports on Sunday. I flew almost 850 miles and logged over 11 hours in the air. In the spirit of the primitive airplane and primitive runways I would visit, I limited myself to navigational equipment that was available when the airplane was new. I found my way using a magnetic compass of questionable accuracy, a mechanical wristwatch, paper aeronautical charts, and the section lines that are visible statewide thanks to dirt roads and changes in farming practices from one section to the next.

All you need to navigate around North Dakota: a decent watch and a navigational chart

The first leg of the trip put my plan to the test. I flew north from Watford City to Columbus, over unfamiliar territory. If the wind blew me off course or I lost track of my position, which I marked with my index finger on the chart strapped to my thigh, I could inadvertently fly into Canada without permission or, worse, have to cheat by using the GPS in my iPhone to find my way. Thankfully, Columbus appeared exactly when and where my preflight planning said it would, and soon afterward I had stamped my passport with the stamp at the airport and started my second leg.

Leaving Watford City

After Columbus came Bowbells and then Towner. I had to use the paved runway at Harvey to get fuel for the plane, and then aimed for Fessenden and McVille. Between those two towns, there is some airspace that is sometimes restricted for military use. Normally, I would call from my cell phone to ask if it is “hot” or “cold” and use a GPS to stay out of it when hot. On this trip, my self-imposed 1941 technology rule required me to stay outside of the restricted airspace using my eyes and landmarks shown on the chart. Along the way, I flew over some kayakers on the Sheyenne River, enjoying the same perfect day from a different perspective.

Something for everyone: a group of kayakers on the Sheyenne River

After McVille, I headed southeast to land between the fields of 8-foot-tall corn at Arthur. Even the most common agricultural activity has an impact on other land uses, and public officials charged with harmonizing land uses should consider all three dimensions. After that, I saw Fargo from the distance as I crossed I-94 to the south on my way to Lidgerwood, where the runway is tucked between sloughs full of reeds and cattails. Next was the smooth grass runway of Milnor, a good example of a pleasant airport that just happens not to have any pavement. The runway was well-maintained and kept clear of any nearby hazards to flight, such as power lines or trees.

Southwest of Fargo: don’t let anyone tell you that North Dakota has no trees

The runway at Milnor is almost completely devoid of obstructions to flight

After Milnor, I flew to the paved runway at Gwinner for fuel and then to Kulm. The sun was about to set when I got there, so I had to stop for the night. Most of the airports I visited are unlit and the Cub does not have the lights that are required when flying after sunset. The Kulm airport was nice for many things, including the manicured grass runway and the air-conditioned pilot lounge. Unfortunately, it was partially surrounded by the airplane’s natural enemy: wind turbines. Planners should talk to airport managers when anything taller than a picket fence is going to be built near the airport. Not only the ends of the runway, but the areas around it that airplanes use for their landing pattern must not have anything to run into.

Wind turbines can be a hazard to flight if they are too close to the ends or the sides of a runway

On Sunday morning, I set out for Gackle, which has two grass runways, both of which are bounded on the ends and sides by water. I was a little nervous about the confined space, as I am not a strong swimmer. Fortunately, the runway I landed on was smooth and I had worried over nothing. Even the airplane seems to be smiling in the picture I took there.

Restored 1941 Piper J-3 Cub at Gackle

My confidence in the plan again soaring, I headed west to Hazelton, then to Mandan’s paved runway for the last fuel stop of the weekend. My next stop was at McClusky, where the runway was badly in need of mowing. It seemed that the airport was not easy to access from the town. Grass landing strips are like city parks: They should not be built too far from where the city keeps its lawnmower. Turtle Lake, my final stop before home, was easy to find: They cut a gap in the shelter belt at the end of the runway so you do not have to worry about hitting a tree when you are taking off or landing there.

The airport at Turtle Lake is easy to find: a green strip with no trees at the end

From Turtle Lake, the trip home was mostly over familiar territory: Garrison Dam, Mallard Island, and the Blue Buttes. It is an axiom among pilots that you should “plan your flight and fly your plan.” That advice applies to many parts of life. Sometimes unpredictable events will occur and you will have to improvise, but having a thorough plan is the best way to avoid surprises. By carefully planning the trip, including the weather conditions necessary for it to work and alternatives in case of mechanical or weather problems along the way, actually flying it was mostly a matter of relaxing and enjoying the view from above.

Overview of my trip on an aviation chart

Ariston Johnson is a partner at Johnson & Sundeen in Watford City, where he represents a wide range of clients including landowners, small businesses, people injured in the oilfield, and the zoning boards of Dunn County and McKenzie County. When he is not working or hiking with his dog, Ari enjoys exploring the world from above in small airplanes.