The Survey is Mightier than the Sword: Statewide Planning Advocacy in North Dakota

by Natalie Pierce, Morton County Director of Planning & Zoning

Editor’s Note: From experience conducting similar surveys from the state level in rural Utah, I laud the approach and efforts of the North Dakota team outlined here. Collaboration between entities is of the upmost importance, as well as collecting solid, defensible data to build state programs and policies. I urge other Western Planners who have been involved in similar state-level survey work in other towns to contact editor@westernplanner.org; let’s share notes and best practices.

The political sphere has always held a magical aura for me. For most of my life, I perceived the legislature to be a place where the levers of power could be activated to cure society’s ills. So when the opportunity came up to represent the North Dakota Planning Association on issues of collective concern during the state legislative session in 2017, I was happy to volunteer. From 2017 to the present, NDPA advocacy efforts have expanded to include a full subcommittee of association members from across the state who work together to develop policy positions and advocate for planning interests.

To begin with, the planning profession itself lies tucked away in a dusty corner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics list of occupational codes and is known to only a small subset of the general population. Likewise, the average North Dakota state legislator (with few notable exceptions) has virtually no base of knowledge regarding the purpose or function that planning activities serve. Bills are introduced each session that are still dripping with the brine of single-issue/single-incident politics. Such bills are not only devoid of any view to comprehensive solutions to complex community issues, but also tear down the already modest set of tools that planners have at their disposal. The 2019 legislative session was particularly grueling: the North Dakota House introduced 546 bills and the Senate introduced 362. Compare that to the 436 and 344 (respectively) introduced in the 2017 session.

North Dakota State Capitol. Courtesy of Bobak Ha'Eri

In presenting testimony at the state capitol, I found myself in repeated contact with the legislative liaisons from the League of Cities, Association of Counties, and Association of Township Officers. By the end of the session we collectively agreed on a couple of items: 1) 2019 thrashed us pretty good. We knew that if the bills we’d helped to “behead” came back as a hydra in 2021, we might be fighting a battle we wouldn’t have the resources to win. 2) The time had come to tackle the ominous task of consulting with political subdivisions across the state to find out what the underlying sources of some of these off-the-wall bills might be. The associations collectively developed a 21-question survey instrument that we rolled out to planners, P&Z Commissioners, and local elected officials state-wide.

The survey was available from September 6, 2019 through January 24, 2020 via the Survey Monkey online platform. The audience for the survey was individuals associated with planning activities for local governments. Notifications to participate in the survey were sent via email to staff and local elected leadership of political subdivisions. The survey team requested specifically that planners extend an invitation to their P&Z commissioners and elected commissioners to complete the survey. Each of the state associations (North Dakota Planning Association, North Dakota League of Cities, North Dakota Association of Counties, North Dakota Association of Township Officers) publicized notices in their e-newsletters and on their websites. The survey team also pitched the survey in-person to audiences at the annual conferences of each of the associations in Fall/Winter of 2019, as well as the North Dakota Main Street Conference.

By the end of the survey window, a total of 212 surveys had been completed. Return rates were as follows: 57% (121 surveys) from individuals associated with cities (of any size), 20% (43 surveys) from counties, 23% (48 surveys) from townships. The highest proportion of returns was from elected officials, with a good sampling of returns from those in other roles: Zoning Administrators, Planning & Zoning Commissioners, and other staff.

It should be noted that all of the survey results figures and tables represent some degree of cross-over. This meant that individuals in various roles from within one political subdivision were all encouraged to return responses. The survey team hoped to triangulate among elected leaders, planning commissioners and staff to arrive at a complete picture of conditions for any given political subdivision.

The survey sought to gather input regarding the issues and needs of political subdivisions across the state, but also to formulate a baseline for the level of resources each political subdivision has at its disposal to support planning activities. Some of the results confirmed generally held assumptions. This was particularly true for the Large City category.

Large cities have resources. Planning staff for large cities generally consists of a whole planning department. GIS software is available. Large cities believe that neighboring political subdivisions have the same or fewer resources to devote to planning as they have. They consider their current zoning ordinance to be satisfactory or good. Long range plans or plan updates have been completed within at least the past 10 years. Finally, they generally have no trouble filling vacant seats on the P&Z commission.

Counties were all over the board. The most common (53% of respondents) planning staff resource for counties was simply a zoning administrator, for whom planning oversight may be a secondary or ancillary function. Around 44% of county respondents stated they had either one full-time planner or a planning department. Most (79%) have access to GIS. Half (49%) of county respondents believe that neighboring political subdivisions have a similar level of resources to devote to planning; the remainder of county respondents were split (23% each) between believing neighbors had either more or fewer resources than their county. One surprising result is that counties’ comprehensive plans tend to be even younger than large cities with 56% of county respondents stating their comprehensive plan was adopted within the last 5 years. Roughly half of counties (44%) have a shortage of applicants to fill vacant P&Z commission seats and, conversely, half (42%) generally have no trouble filling vacant seats.

Perhaps the most striking results of the survey were those that illustrated the level of resources for planning within small cities and townships. Among half (46%) of small cities within the survey sample, planning staff consists of only a zoning administrator. 26% of small cities have no planning staff at all. Planning staff for the remainder of small cities is a mix ranging from occasional consultants to a full planning department. Small cities and townships generally responded that neighboring political subdivisions have the same level of resources they do. Roughly half of small cities (44%) have access to GIS, whereas only 29% of townships have access to GIS.

Within the township category, planning staff consists of a zoning administrator for 29% of respondents, while 43% of respondents were in a township where no one is assigned the responsibility of overseeing planning and zoning activities. Interestingly, despite there being very little planning staff within small cities and townships, the majority of those respondents feel their zoning ordinance is satisfactory to good.

Among small cities, 40% of respondents stated that their comprehensive plan was adopted more than 20 years ago or does not exist, to their knowledge. This proportion rose to 63% among townships. Among township respondents, 63% are operating without a P&Z commission at all. The characteristics of P&Z commissions among small cities was more varied (see figure 1).

Figure 1

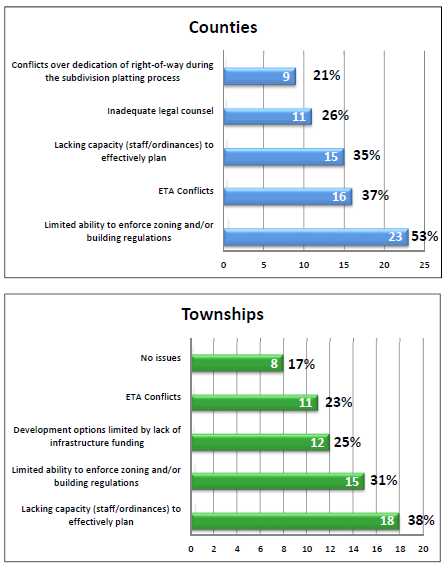

Survey takers were asked to name the most significant, ongoing planning and zoning challenges facing their political subdivision. Survey takers could choose from a long list of choices or provide an open-ended response. Below are charts that list the most frequently selected choices, by political subdivision category.

Figure 2

The charts illustrating the self-reported greatest planning-related needs of political subdivisions are worth sharing in full. Common needs across the board are P&Z commissioner education/training, better tools for zoning enforcement, zoning code and/or long range plan updates, and access to legal counsel with expertise in land use law.

Figure 3

Despite the identification of these needs, the majority of survey respondents (across all political subdivision categories) did not believe that legislative changes would resolve the planning issues they are facing. Of the minority of respondents (21%) who believe that the issues they face do require legislative solutions, they believe that such legislative solutions are moderately urgent (3) to extremely urgent (5), on a scale of 1 to 5.

In North Dakota, one bill that has been—and will likely continue to be—introduced is a bill to eliminate the extraterritorial zoning authority that allows cities and townships to plan outside their borders for future growth. Our survey team wanted to understand what local concerns continue to drive this bill session after session. Among all survey respondents 81% believe extraterritorial authority should be preserved with 33% believing the extraterritorial authority is useful but the policy framework could use some revisions. 19% of all respondents (including 45% of township respondents) believe extraterritorial authority should be eliminated altogether or replaced with a different type of policy.

Survey respondents were asked to further describe the issues they observe with regard to extraterritorial authority conflicts. Large cities provided many reasons why the framework is critical to planning for future growth. Some responses illustrated that extraterritorial areas can become a dumping ground for problems that either involved jurisdiction does not want to deal with. Conflicts can arise when city, township and county policies in the extraterritorial areas are not aligned. When a jurisdiction has extraterritorial authority but no planning staff or expertise to adequately manage that authority, it creates problems. Overall, many of the issues cited in the comments pointed back to the need for neighboring political subdivisions to work on fostering functional, collaborative relationships with one another. Within the township category of responses, some stated that their voice gets drowned out in extraterritorial authority matters when competing interests with larger political subdivisions are in play. Another stated that some cities take extraterritorial authority but then do not take the trouble to enforce regulations. This recalls the related issue of needing stronger tools from the state and/or more resources to enforce zoning and building codes. Other comments alluded to the confusion among residents who live in one jurisdiction but have to follow the rules of electors from another jurisdiction who they can’t vote for, or against.

Interests from the real estate appraiser community supported the introduction of a unique bill in 2019 that attempted to override residential non-conformity regulations in local zoning codes statewide. The bill would have entitled by-right all residential structures (which was not defined in the bill language) to be reconstructed if damaged beyond 50% of market value, regardless of whether the structure, the use, or the property itself might be in a non-conforming status. 46% of all respondents stated that if the bill were to be introduced next legislative session, opposing the bill would be “important” or “extremely important” for them. 46% of all respondents said opposing the bill was neither important nor unimportant. 8% stated it was either unimportant or they would actually support passage of the bill.

The last question provided a link to an interactive legislative district map, and asked survey respondents to provide the number(s) of the legislative district(s) of the political subdivision the respondent represents. The question instructed the respondent to list “Large City” for cities with a population of over 15,000 so as to conserve the anonymity of respondents for whom listing a legislative district would pinpoint their location. Surveys were returned from every legislative district in the state.

The survey provides an invaluable starting point to tease apart the roots of some complex issues and concerns. The state associations are already well into the process of crafting legislative advocacy agendas in advance of the 2021 session. The intention at this point is to collectively discuss the results of the survey and formulate some policy objectives for the 2021 session (or beyond) that the associations can present to the legislature on a unified front. At a minimum, the survey results will be presented to the House and Senate Legislative Committees.

One of the most significant take-aways from the survey pointed to the serious need for more widespread education about planning and—dare I say—marketing the tenets of planning to make them household words. The onus of public engagement is perpetual and extends to the highest levels of government. In the West, where many planning professionals are accustomed to working with a staff of one, it is still imperative to carve out some amount of time to advocate for more planning awareness and perhaps resources at the state level to assist in that effort. The more we can convert leaders and members of the general public over to being informed and avid planning advocates, the less work we’ll theoretically have to do in the long run when we’re asking for regulatory tools and resources to make good planning happen.

The survey results report will be available on the www.ndplanning.org website: check back for updates.

Author Bio

Natalie Pierce is the Planning & Zoning Director for Morton County, ND. Natalie holds a Master of Urban and Regional Planning degree from the University of California, Irvine and a bachelor’s degree from Barnard College in New York City. She lives in rural Morton County with her husband and two young sons.