Healthy, 10-Minute Neighborhoods

by Dr. Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard

In a healthy 10-minute neighborhood most trips – to school, shops, services, work, recreation, and public transit - can be made by foot or bike within 10 minutes. To improve physical health we know we must transform our cities into a networked system of 10-minute neighborhoods. By reducing car use, this will also be more ecologically friendly. When people walk they are more likely to begin to recognize neighbors, talk, and build social networks; this is invaluable for strengthening individuals’ social immune system, reinforcing social bonds, and developing kids’ social skills.

How are cities around the world tackling this challenge, and which models offer the best solutions for Western cities? How well do the cutting-edge developments fulfill these principles? How are cities transforming mistakes of the past (sprawling suburbs, unwalkable streets, etc.) into vibrant neighborhoods?

In his new book, Within Walking Distance, New Urban News Editor Philip Langdon describes six walkable neighborhoods in US cities – Philadelphia, New Haven, CT, Brattleboro, VT, Chicago, Portland, OR, and Starkville, MS. Langdon is convinced that “places organized at the pedestrian scale are, on balance, the healthiest and most rewarding places to live and work."[1]

A certain density is required to support all necessary resources within a 10-minute neighborhood, but a growing body of urbanists is convinced that the healthiest density is better achieved in a human scale urban fabric, rather than through high-rise development.

Transforming existing neighborhoods

Some cities are taking bold steps to transform unhealthy sprawling suburbs into walkable neighborhoods. Other cities are transforming dense districts overburdened with traffic into healthy walkable neighborhoods.

Photo provided by Dr. Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard.

Under the leadership of Mayor James Brainard, Carmel, Indiana is creating a compact, walkable, city center in what used to be merely a sprawling bedroom suburb of Indianapolis. Over the last 20 years, Carmel (pop. 90,000) has seen a dramatic transformation. Here, the first job was to create a strong, compact, walkable, human-scale, mixed-use city center that draws people of all ages to its beautiful squares, parks and trails. Residents strongly support the concomitant traffic calming (with now over 100 roundabouts) and identify with the classically-styled architectural language of the growing city center. In 2017 Carmel was voted the most livable city in the US.

Scott Jordan, Principal at Civitas, asserts that Denver is leading the way in generating new urban neighborhoods on under-utilized sites by focusing on transit, enhanced pedestrian experiences, and a robust parks system. The revitalization of the blighted Central Platte Valley spurred multiple urban plazas and a series of mixed-use communities. Villa Italia Mall, with its 100-acre parking lot was transformed into Belmar, a new urban neighborhood with mixed-use development, shops with residential above, and a square at its center. The former Stapleton International Airport has become one of Denver’s most prized new neighborhoods. These developments include a mix of scales and varied levels of urbanity.

Photo provided by Dr. Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard.

Barcelona's density of 16,000 inhabitants per square kilometer is one of the highest in Europe. In many neighborhoods around La Sagrada Familia the density is higher than 50,000 per square kilometer. This density is achieved thanks to the six-story mixed-use grid plan urban fabric laid out by Cerda in the 19th century.

Until recently, the public transit system was unable to handle the volume of commuters, so cars dominated the streets, causing major air pollution. Now, the network of commuter rail, metro, trams and buses has been vastly improved and interconnected, making it easier, less expensive, faster, and more convenient not to take the car. But old habits need to be changed.

A traffic-free square in Barcelona’s Superblocks. Photo provided by Dr. Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard.

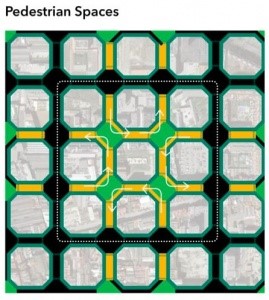

To encourage people to walk, bike and take transit, the city is introducing the “Superblock” program, whereby two out of every three streets will be transformed into a traffic calmed street (woonerf), or pedestrian and bike street, and intersections will be turned into green plazas. This will make every neighborhood in Barcelona more healthy, livable, sociable, walkable and bikeable. This model, designed by Salvador Rueda, Director of the Office of Urban Ecology, may be relevant for many Western US grid-plan cities. Barcelona’s Mayor Ada Colau will receive the IMCL City of Vision Award for this work at the 55th IMCL Conference in Ottawa, BC in May.

Human scale neighborhood infill

Photo by Design Archive

Our large Western cities – Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, etc. - are under pressure from developers to reach for the sky, but negative side effects (increasing unaffordability and inequality, damage to the public realm, etc.) may outweigh the benefits. Jennifer Keesmaat, former Toronto Planning Director, argues that the most successful developments have been in the mid-rise range of 5-6 story, mixed-use continuous urban fabric. Her primary concern has been to create places where people flourish: human scale mixed-use neighborhoods.

In Poland’s capital city, Warsaw, Director of Architecture Marlena Happach has announced that the city is moving away from the recent deeply unpopular high-rise development to human scale infill in the neighborhoods along their new Metro line east of the Vistula River. Many citizens feel the high-rise developments destroyed Warsaw’s identity and created an unattractive urban environment. Happach wants to create neighborhoods that are more affordable, walkable, and “a good place to live.”

New 10-minute neighborhoods:

Photo provided by Dr. Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard.

Some cities are creating new compact human-scale mixed-use neighborhoods on brown or greenfield sites. The transit-based new neighborhoods, Rieselfeld and Vauban in Freiburg, Germany have won many awards for their sustainable designs, low-energy use, and child-friendliness. The developments were supervised by Dr. Sven von Ungern-Sternberg, Mayor, who has been in charge of urban planning for 20 years. Special attention was paid to human scale, small footprint, low energy use buildings, ecological landscaping, pedestrian and bike transit. We can see today how well the goals have been achieved.

In the UK, Poundbury, master planned by Leon Krier, was conceived as a cluster of walkable 5-minute neighborhoods creating a compact urban village on the outskirts of Dorchester. Begun in 1993, with key buildings by Britain’s most accomplished traditional architects, Poundbury is now 75 percent completed. The latest addition is the very heart of the community - Queen Mother Square, framed by the Royal Pavilion apartments; the Strathmore (luxury condo building); the Dutchess of Cornwall hotel, pub, and conference center; plus offices and shops.) Poundbury is maturing. It has a mixed demographic, a growing population of young families, and over 35 percent affordable housing. There are shops, services, industry, and workshops; two- thirds of which are run by women.

Several new walkable 10-minute neighborhoods designed by architect Maxim Atayants are being constructed in St. Petersburg and Moscow, using a classical architectural vocabulary to create a traditional 5-6 story urban fabric that shapes parks and squares. This approach emphasizes the importance of the public realm as a place for social life, and surrounding architecture as a ”gift to the people,”[2] enhancing the experience.

Near Paris, France, is Plessis-Robinson, one of the finest walkable new neighborhoods that replaces a monotonous modernist public housing project. Plessis-Robinson is planned with mixed-use, and a contiguous human-scale urban fabric of small footprint buildings. The areas designed by Francois Spoerry (the heart of the town), Mark and Nada Breitman (market-rate rentals and social housing), and Xavier Bohl (1,300 dwelling units, including 250 units of social housing, and 6,000 square meters of businesses and public uses) employ delightfully varied traditional architecture that interweaves parks, streams, and lakes along a pedestrian/bike spine.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of these vastly diverse approaches? Who benefits and who loses? Are there ideas we can borrow or solutions we can adapt for our own cities? In comparing different cities around the world, can we learn how to more effectively achieve healthy, 10-minute neighborhoods in our own city? We must be willing to learn from the best. This is the goal of the 55th International Making Cities Livable Conference on Healthy, 10-Minute Neighborhoods, in Ottawa, BC May 14-18, 2018, one of the longest-running and most sought-after global urbanism events.

Ten-Minute Neighborhoods are the future! Join us in Ottawa, BC May 14-18th 2018.

Endnotes

- Langdon, Philip. (2017) Within Walking Distance. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Siena’s first democratic city government in the 13th century specified design guidelines that ensured façade designs would be “a gift to the people.”

Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard, Ph.D.(Arch.), is Founder (1985) and Director of the International Making Cities Livable Conferences, and Consultant to cities in the U.S. and Europe. Dr. Crowhurst Lennard has held academic posts at the University of California, Berkeley, and Brookes University, Oxford, England. She has been Visiting Professor at Harvard University, and City University New York, and Guest Lecturer in Architecture and Planning Departments in the U.S., Great Britain, Germany, Austria and Italy. She has received awards from the NEA, NYSCA, RIBA, and the Graham Foundation.

Published April 2018