King Cove, Alaska - Chapter Two: Water Into Powerhouse=Light

Downtown King Cove. Photo from Gary Hennigh's presentation to the 2017Arctic Energy Summit.

Editor's Note: This article is a follow-up to the 2015 article "Doubling Down on Small-Scale Hydro - Government that Works"

by Gary Hennigh, King Cove, Alaska

No matter where you are as you read this, or what the view is out your window, chances are good that water matters to you. Water irrigates, water transports, water cools us and heats us and sometimes, it washes away the bad parts of a day. It comprises 60 percent(1) of the human body and from its depths, more than 3.5 billion people around the world are fed.(2) And in King Cove, Alaska, where I’ve had the privilege of being City Administrator for almost 30 years, if all goes as we have dreamed it, planned for it and gone deeply into debt over it, water will provide the light by which our city’s grandchildren will read their children to sleep. And, best of all, it will do so at a fraction of the cost and diesel exhaust that was otherwise guaranteed to be their future.

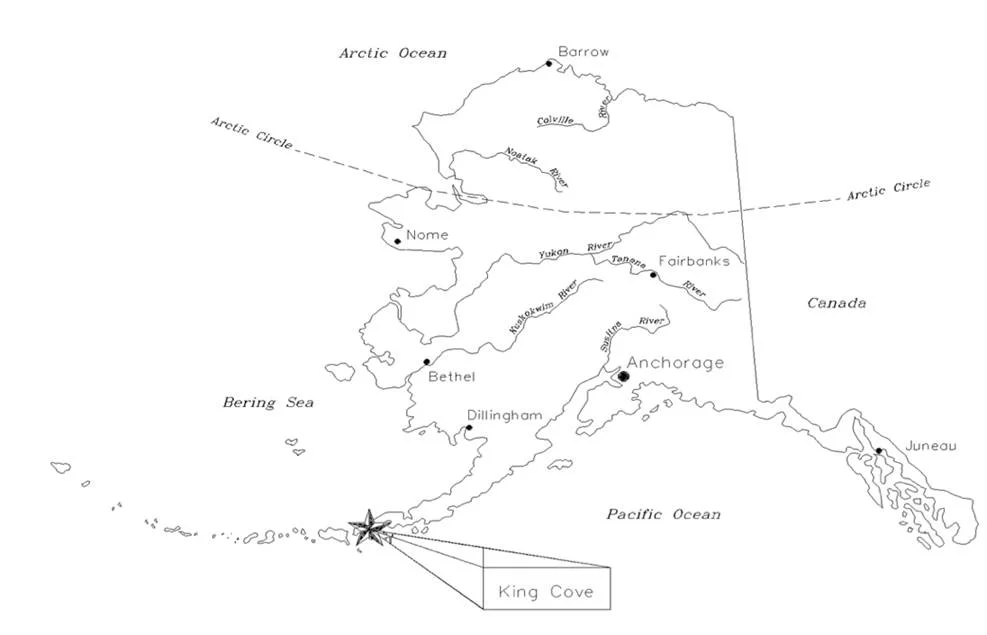

Map provided by Gary Hennigh.

Dug in between volcanic mountains and the sea, the land holds in reverence the bones of King Cove’s Aleut ancestors; the indigenous Alaskan natives that have a 4,000-year-old(3) history with this place. If you have Native Americans among your constituencies, then you know that they bring a responsibility for their heritage to every meeting at which decisions about the future will be made. It may also sound familiar that they wear their survival skills as a second skin, so in tune are they to the truth that the future is only ever claimed by the risk-takers, in partnership with those who persevere and possess an ability to learn from their mistakes.

King Cove (pop. 900.) is a place that could be used to illustrate the dictionary meaning of rural, rugged, wind-swept and fog-shrouded. Its very geography demands a respect for the forces of nature and yet that same geography is paying big dividends to the residents, and with some foresight and upkeep, will continue to do so for decades to come. As one of the largest Aleut communities in Alaska, it is not surprising that its history is measured in millennia. As one of the few communities that enjoys 75 percent of its electricity from a renewable source, it is also likely to be here millennia from now.

King Cove has had its name on a map since 1911, when a predecessor of Peter Pan Seafoods chose it, straddling the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea as it does, as an ideal site for a cannery to serve the western end of the Alaska Peninsula.(4)

Now, a 107 years later, it is a vibrant community of 900 people and home to the largest “wild” salmon cannery in North America, including year-round crab and bottom fish processing. (If you haven’t tasted wild-caught Alaskan seafood I recommend it - the best in the world!) Because King Cove is home to a single processor, how much data NOAA is authorized to release is limited by confidentiality concerns. Were it not for that restriction, our place on NOAA’s Top 15 list of major U.S. ports for annual, commercial fishery values, would be routine. What I can brag about are our two major boat harbors and that the ex-vessel value of our fisheries is between $45 and $60 million annually. Those numbers have held true for the last decade.

We are serious about fish as the backbone of our economy. But we are just as serious about securing stable utility costs through the development of two renewable energy projects. In my last piece for Western Planner, published in the summer of 2015,(5) I told the story of a little town that could and did take bold risks in its pursuit of renewable energy for its citizens, and how it did so at a time in the 1990s when run-of-the-river hydro-electric technology was in its infancy, and particularly unheard of in rural Alaska generally and remote communities the size and location of King Cove in particular. While there were challenges with an undertaking of this size, from the moment we turned the switch and brought it online in 1994, it has provided 50 percent of the city’s electrical needs.

Delta Creek Hydroelectric Facility. Its creation is covered in an 2015 WP article.Photo from Gary Hennigh's presentation to the 2017Arctic Energy Summit.

Delta Creek Powerhouse with Waterfall Creek in Background. Photo provided by Gary Hennigh.

The second project, called Waterfall Creek, was not yet a physical reality when I wrote the 2015 piece. But we were energized to break ground on construction and anxious to find financial partners to assist us in its completion. We understood the value of our good fortune to have found another near-by creek, for which the engineering penciled out and much of the already-built Delta Creek infrastructure could be utilized.

All the same sources of funding for Delta Creek were not there for us on Waterfall Creek. Nonetheless, the city looked ahead to projected fuel savings from having at least a full 75 percent of its power from a renewable source, and we decided to go all in with the city’s good credit to make this project a reality. And in May 2017, we had the gratifying experience of seeing it come online, a dream realized.

But it was an expensive dream and the debt the city has taken on is a heavy yoke to bear, even with our electric utility fund being financially sound. The final cost of Waterfall Creek is $6.5 million. It will be paid for through $3.3 million in grants from both the Alaska Energy Authority “AEA” and Aleutians East Borough, $300,000 in direct cash from the City of King Cove, and $2.9 million in long-term debt. The $2.9 million in debt is comprised of $1.5 million from the Alaska Municipal Bond Bank and $1.4 million from AEA’s Power Project Fund. Annual debt from these sources is $225,000.

These expenses run concurrently with the indebtedness that we incurred for Delta Creek. The annual debt for Delta Creek is $150,000, and we’ve made payments beginning in 1995. In 2020 we will make our last payment on this project, representing a 25-year commitment to the wisdom of hydroelectric power.

This amount of debt – combined with no longer receiving a state energy subsidy offered to small rural communities like ours – is problematic. Consequently, the city is seeking to reduce our debt on Waterfall Creek by at least $50,000 annually. We’d like to make our case to our State and Borough governments and secure commitments of $500,000 in grants. We think we have an argument that being “disincentivized” for our success runs counter to the goal of encouraging communities like ours to take such a huge, financial plunge.

The beauty of civic projects like ours is their ability to reward us with good data. Since last May when Waterfall Creek came online, and through February of this year, fully 75 percent of our electricity has been from these renewable sources. 64,000 fewer gallons of diesel fuel were burned at a savings of $175,000 (@$2.75/gallon.) Several times, even in winter months, we witnessed the community being powered by 100 percent hydropower. For a city planner, those are great moments.

We are proud that our projects were recognized by the International Energy Agency’s Hydropower Group and that we were included in their Good Practices report.(6) This report reviewed and provided detailed critiques of 23 small hydro systems around the world. And I was honored to travel to Helsinki, Finland in September 2017 to participate in the Arctic Energy Summit. King Cove was selected by the participants as a “best practice” example of community renewable energy independence in the Arctic. This selection will be included in the final Summit report to be delivered to all eight Arctic nations.

Renewable energy is the future. In King Cove, city and borough leaders decided the future is now. The hope was to save dollars and diesel. But the dream was to make a world that our children will be proud to live in and proud of those who delivered such a world. We want to earn the respect of the young woman whose face appeared on the front page of our state’s major newspaper, (7) Anchorage Daily News, last November. It was a photograph of a confident, 24 year - old young woman smiling into the camera. Her name is Samantha Mack and she is the first member of her family to get a college degree. She is one of 32 young scholars chosen to be a 2018 Rhodes scholar. She is the first University of Alaska student to be selected for this prestigious academic honor. She is the first Alaska Native to be so recognized. And her life began in King Cove. The Macks were one of the original families to form King Cove over a century ago. Her great-grandfather came from Germany to fish and married a local Aleut lady. They had 18 children together. So Samantha is very much of this place.

Soon she will be off to Oxford, a very long way from home. She wants to return as a University professor focusing on the high attrition rates of Alaska Native students. Her indigenous studies took her deeply into the Aleut people’s rich and complicated past, and it lit something in her. She wants to teach others what she knows, and she wants to do it here in Alaska.

Risk-taking is not for the faint of heart. Failure is always possible. Yet, the rewards are soul-satisfying as Samantha will attest. We hope Samantha will travel far and wide and tell the story of her people and her beginnings, and what it’s like in her hometown. Because we are proud of her story and we are proud of how her story intertwines with King Cove’s.

This job has occupied the majority of my adult life. My beard wasn’t grey when I started and my phone came with a cord. Email was just catching on. Yet for all the years of working for this community, seeing it grow and prosper, I remain inspired, because not only is the landscape always changing, the people themselves are always looking ahead. (They have a story to tell about their decades’ long struggle for a connecting road to Cold Bay. But that is for another day.)

For now, I revel in this view of our harbor at night. The photograph captures for me all of the ways that water defines and supports this community. It is income and food. It rewards the well-prepared and in an instant can pull you under. It is always present. It is always evolving. It falls as rain and it crashes as waves. And it flows to the sea as Delta and Waterfall Creeks. As they make their way, we have invited them to do so by way of our powerhouse, an invitation we have helped them to accept. We are thankful for the energy they leave behind. We are humbled by the thought, that if we did this right, and dreams come true, light derived of their water will shine on generations of Mack children, illuminating their way to a better life.

Downtown King Cove, Alaska. Photo provided by author.

Endnotes

Gary Hennigh has been the City Administrator for the City of King Cove, Alaska for the last 28 years. His proudest achievements are being the catalyst in shaping King Cove to be one of Alaska’s premier renewable energy communities. Prior to his current position, he was the Community Development Director for the City of Valdez, Alaska during the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. Gary is a 40-year resident of Alaska. He has an undergraduate degree in geography and a Master’s degree in regional planning from Penn State University. He enjoys hiking, fishing, cross-country skiing, and simply loves the great Alaskan outdoors!

Published April 2018