Citizen Planner Main Street Assessment

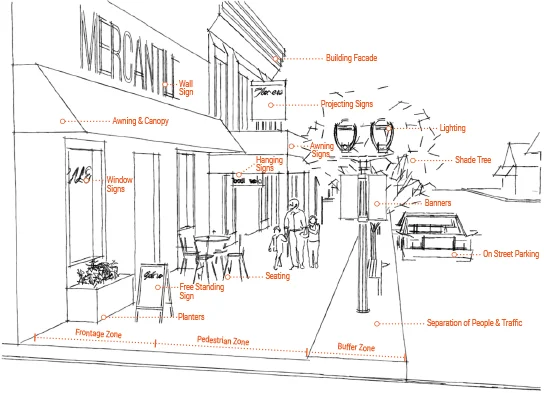

The Main Street Sandwich Method guide introduces urban design terms commonly used in code to help demystify planning language. PLANNING GRAPHIC INSPIRED FROM ANDRES DUANY, ADAPTED TO ILLUSTRATE THE VARIOUS SEGMENTS OF A TYPICAL RURAL MAIN STREET IN CONTEXT (Duany & Talen, 2001).

by Paul Moberly, AICP, Utah

Special thanks to Aubrey Larsen, Flint Timmins, and Kyle Slaughter in Utah’s Community Development Office for their ideas, thoughts, edits, and contributions.

Successful communities recognize the importance of Main Street; it is the community’s “public face” and often serves as the cultural, social, and economic center for small communities. Residents, workers, and visitors benefit from the access to goods, services, amenities, employment, and opportunities to participate in the community life that main street provides. Since Main Streets serve as core components of both community and economic development, they can be an engine for revitalization and prosperity; conversely, losing such amenities and gathering places can dramatically weaken any community’s identity and can contribute to an economic downturn.

Many small cities and rural towns in Utah struggle to keep their main streets viable and thriving. Due to the lack of paid planners and a state-sponsored Main Street program in Utah, many communities are left without the necessary resources to address struggling, unattractive main streets—many don’t know where to start. The State of Utah’s Community Development Office (CDO) saw a need for a simple, quality resource for citizen planners to use so that they can confidently assess their local main streets and identify needed improvements, then move towards positive change. They created the award-winning Main Street Sandwich Method for rural citizen planners to help assess a community’s main street.

The best main streets are built like your favorite sandwich. The buns hold everything together while the condiments add flavor and compliment the meat. Just as a hamburger differs from a turkey hoagie, each community’s main street has a different “flavor,” emphasis, or makeup that makes it unique. An excellent main street supports the needs of residents, businesses, tourism, and recreation alike.

Just like a great sandwich has different ingredients with different roles, the sandwich metaphor in Main Street Sandwich Method is used three ways: one, to examine the various segments of a Main Street individually; two, that a good Main Street is made up of a variety of different elements unique to each community; and three, that the assessment should similarly be unique to the community and situation.

A familiar planning graphic adapted to illustrate the various segments of a typical rural main street in context.

The Main Street Sandwich Method is specifically tailored for small towns and citizen planners. It helps those not otherwise familiar with urban planning look at and understand their main street and identify opportunities for improvement. Local residents are the experts on how their community functions. They are intimately aware of what is going on but lack methods and language to express their understanding. Community member input and participation in a Main Street planning project are essential because not only are they local experts but any changes that are made will directly impact their lives. The Main Street Sandwich Method aims to facilitate and empower the involvement of local citizens. It first breaks down Main Street into three distinct segments which should be individually evaluated:

GATEWAYS (Buns):

Located at each end of Main Street, a gateway signals that you have arrived or that you are leaving town. Gateways hold main streets together and define your sense of arrival and departure. They can be a sign, a cluster of buildings, a landmark, or anything else that signals arrival or departure to the community via Main Street. When Main Street is a highway entering a town, the gateway is an important identity and wayfinding element.

TRANSITION AREAS (Condiments):

Located between gateways and the core, transition areas should provide clear wayfinding (signs) to important destinations as well as prepare visitors for the core by slowing traffic. Transition areas create first impressions of town but are frequently neglected.

CORE (Meat):

The core or downtown of Main Street is a destination and often forms the identity of a community. A good core provides a variety of experiences, activities, and is an inviting place to be. Comfortable places to sit, walk, and eat are essential. The core should make visitors want to get out of their car and experience what the community has to offer.

While the majority of a town’s focus will be on the core, the Main Street Sandwich Method encourages communities to examine the entirety of their main street as an interconnected center of the community. While examining the whole main street, the initial groundwork for any sort of main street improvement project must begin by establishing what is in need of improvement. The Main Street Sandwich Method provides rural communities with guidelines and tools for conducting a successful evaluation of their Main Street. Having this type of methodology and process is useful for gathering credible local evidence for action. As the Project for Public Spaces stated, “By providing concrete evidence of a problem or of an opportunity to make things better, a community can build its case for enacting positive change.” (Espiau, Renee and Burillo, Renee. (2008). Streets as Places: Using Streets to Rebuild Communities. Project for Public Spaces, Inc. www.pps.org/pdf/bookstore/Using_Streets_to_Rebuild_Communities.pdf).

Integrating best practices, the Main Street Sandwich Method uses multiple assessment tools to look at all the attributes of main streets. The methods included can be used in multiple ways by staff or in public meetings for citizen engagement. It first prepares users for the assessment by describing roles and forms of Main Street and then evaluates Main Street’s performance. The methods include:

- Preparing for your assessment

- Simple survey for all parts of the main street which examines the arrival, impressions, and transition to the core. In the core, it directs surveyors towards basic elements of design, safety, security, comfort, access, and interest.

- Perspectives exercise called “Purpose from Perspective” where participants proverbially walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. Surveyors or participants imagine experiencing the main street from the perspective of various people (e.g., six-year-old child, retiree, college student, mother of young children, etc.)

- Brief, 2 minutes on the street surveys for individuals and business owners.

- Simple way of documenting different uses

- Quick audit of vacant buildings and parking

- Guide for marking up a map of the main street

- Main street form snapshot with notes

- SWOT for streetscape and overall

- Brief guide for after completion of the assessment

The guide can help people think from various perspectives when considering their main street.

Many of these methods have been used independently and can be easily adapted. For example, the Purpose from Perspective method was used successfully in a highly divided town to develop common frameworks and identify united priorities for their main street. The growing tourist town had a major divide between those who desired tourism and those who resisted its promotion. Town leadership was nervous that strong opposition would gridlock any forward visioning for their main street core. Consulting planners used the Purpose from Perspective approach to try to diffuse any tension.

During a public meeting to discuss a vision for Main Street, planners implementing this method began by introducing hypothetical, but realistic people including: a little girl, a teenage boy, a visiting college student on break, a mother of young children, an elderly retired resident, a local business owner, and a lifetime “old-guard” resident. Each of these people was given a backstory, preferences, and context for their activities on Main Street (e.g., the six-year-old girl Kaylee is learning to ride a bike, and crosses to attend school; the college student goes out hiking and wants somewhere safe to drink and socialize afterward). Then the planners asked the residents to list what they think each person’s goals for the main street would be. For example, Kaylee, the little girl learning to ride her bike, wants to cross safely, ride her bike without being scared by loud cars, find ice cream, go to the park; Kathy the business owner wants visibility, customers driving slowly past her storefront, advertising space, easy parking, good lighting, etc.

Pulling the residents out of their own entrenched views and opinions, the townspeople were asked to adopt the perspective of each of these fictional people and rationally express someone else’s top concerns, and how other’s would rate the current structure and function of the main street. After dialog around these neutral perspectives, the goals that the townspeople identified for each of the fictional characters were compiled into common macro-themes. The planners then presented these themes to the townspeople and asked if they supported them as well. These were basic but foundational for setting common goals, such as safety for all, good wayfinding, relaxing social spaces, dining options, and retaining local heritage.

This process enabled the planners to avoid discussing tourism, traffic, or parking conflicts and bypassed local political rifts that had formed. Once these common priorities and goals were formed, it helped the town to understand the space could be enjoyed by all. The Main Street Sandwich Method guide includes a simplified version of that approach that can be used as a simple survey or adapted for a similar public meeting approach. The guide places multiple simple methods, like the Purpose from Perspective method, at the disposal of citizen planners.

While many tools exist to assist cities to assess and improve main streets, those are largely intensive projects that rely on capital, knowledge of urban planning and design, and a program. While these are certainly beneficial, small towns and citizen planners may not always be able to access these resources. The Main Street Sandwich Method uses several simple evaluations for users to quickly and effectively lay the groundwork for a main street improvement project or program. The guide prompts users to look for certain attributes with a critical eye, take notes as they walk the street, and identify improvement opportunities. By using a sandwich analogy, the Main Street Sandwich Method makes a daunting task fun, relatable, and memorable.

In preparing this guide, Utah’s Community Development Office (CDO) researched best practices in community engagement, urban design, and main street revitalization. CDO obtained the input from industry professionals, including local government urban planners and faculty from the USU Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning department. The CDO tested elements with various communities, and at the Spring 2017 Utah APA conference, CDO conducted a walking tour of Brigham City’s main street using the guide for attendees. It has been tested in several other small communities in Utah and is starting to be used outside the state. One community leader stated “I was grateful to receive the assessment and shared it with our Planning Commissioners and staff. As we begin to update our General Plan in Layton …it has opened up some great discussions amongst Planning Commissioners and staff. I thought that was a most engaging and productive exercise.” The input and feedback received were crucial to creating a usable resource for small towns across Utah and rural America. The CDO continues to share and refine the guide.

The guide is meant to be part of a typical planning process: helping leaders gain insight and information into their community. Each element of the guide can be adapted for public meetings and citizen engagement. Leaders, professionals, and citizen planners can use pieces of the guide as an idea generator for public engagement techniques or take the whole guide as a worksheet for self-assessment. Once the information is collected, leaders can create well-founded programs, draft informed policies, and plan intelligently for their Main Streets.

The guide is adaptable to each small town’s unique needs. Its discussion of principles and variety of assessment tools ensure that all users can walk away with a greater awareness of their main street needs and confidence in their ability to improve the street. This guide helps small towns become self-reliant, self-determined, and prepared for the future. Download the guide to use in your community at http://www.ruralplanning.org/main_street_audit.

Further Reading/References

- Espiau, Renee and Burillo, Renee. (2008). Streets as Places: Using Streets to Rebuild Communities. Project for Public Spaces, Inc. www.pps.org/pdf/bookstore/Using_Streets_to_Rebuild_Communities.pdf

- The Main Street Sandwich Method. http://www.ruralplanning.org/main_street_audit.

Utah’s Community Development Office

Organized in 2017, Utah’s Community Development Office supports planning and community development throughout Utah with technical assistance and grant administration. Part of Utah Department of Workforce Services’ Housing and Community Development division, the Community Development Office develops and delivers training, tools, and resources to build communities which are self-reliant, self-determined, and prepared for the future to which they aspire. Visit http://ruralplanning.org/ for more information.

Paul Moberly, AICP, is a Community Development Specialist with Utah's Community Development Office, part of Utah Housing and Community Development, part of the Utah Department of Workforce Services. With a background in international business and marketing communications, Paul focuses on community and economic development, quantitative data analysis and community design. A long-time student of rural issues, he's consulted with rural towns throughout upstate New York, the Adirondacks, and Utah and has studied rural decline during the past decade throughout the Northeast and Northwest. He holds a Masters in Regional Planning from Cornell University, and a community development-focused Masters in Education from Boise State University.

Published in January 2018