How Zoning Can Help Fix the Housing Crisis in America

by Jennifer Murillo and Monica Szydlik, Lisa Wise Consulting, Inc.

While there is no single action that will solve the housing shortage we are facing in the Western States and the U.S., the potential approaches discussed in this article focus on actions jurisdictions can take to refine their municipal codes to help alleviate the imbalance. They include successful examples from California, Arizona, and Ohio.

76% of rural community voters and 74% of suburban community voters agree that “America has a housing shortage, and we need more homes and rentals.” (Turner & Radosevich, Center for American Progress, 2024)

Most voters agree that there is a mismatch in the supply and the demand for housing in the U.S, particularly in the Western States. It’s not a rural or urban problem but “persisting across geographies and typologies of place” (Garcia, et al., Up for Growth, 2024). It’s not just a moral and ethical issue, but an economic one as well. In a 2016 report by McKinsey & Company, Closing California’s Housing Gap, it was estimated that California lost $140 billion dollars annually from excessive commute times, lost construction investment, and foregone consumption of goods and services, because Americans spend so much of their income on housing.

In a 2023 National League of Cities survey, local leaders identified the most common housing supply hurdles in the West as: construction obstacles (27%) and financing challenges (22%), followed by land use, zoning, and permitting obstacles. This article focuses on the latter. What cities can do to make housing more accessible to a greater number of people by streamlining and updating the regulations that impede housing production.

The approaches in the article align with amendments described in the American Planning Association’s Equity in Zoning Policy Guide, which identifies ways “zoning regulations can be changed to dismantle the barriers that perpetuate the separation of historically disadvantaged and vulnerable communities” (2022), and Housing Supply Accelerator Playbook, aiming for diverse, attainable, and equitable housing.

Zoning Amendments to Support Housing

Although approaches vary based on local context and conditions and market factors, the amendments discussed herein are meant for consideration by communities looking for effective approaches to address the mismatch of housing supply and demand.

Ministerial Approval + Objective Design Standards

Objective standards involve no personal or subjective judgment during local review and are uniformly verifiable by specific criteria (measurable or quantified standards). (California Government Code 65589.5(f)(9)

Ministerial approval, or “by-right” approval, is a potentially effective tool to facilitate the production of housing. Ministerial approval is a nondiscretionary development review approval conducted by municipal staff. When ministerial approval is combined with objective design standards, the result is a more predictable review process with a more predictable development outcome.

Objective development and design standards can help garner support for ministerial approval as the standards identify the precise requirements (or options) that implement the community’s design priorities. The first step is to evaluate current development standards and design guidelines to understand how closely they are aligned with the community’s vision and, then, how they could be converted into measurable or quantifiable standards.

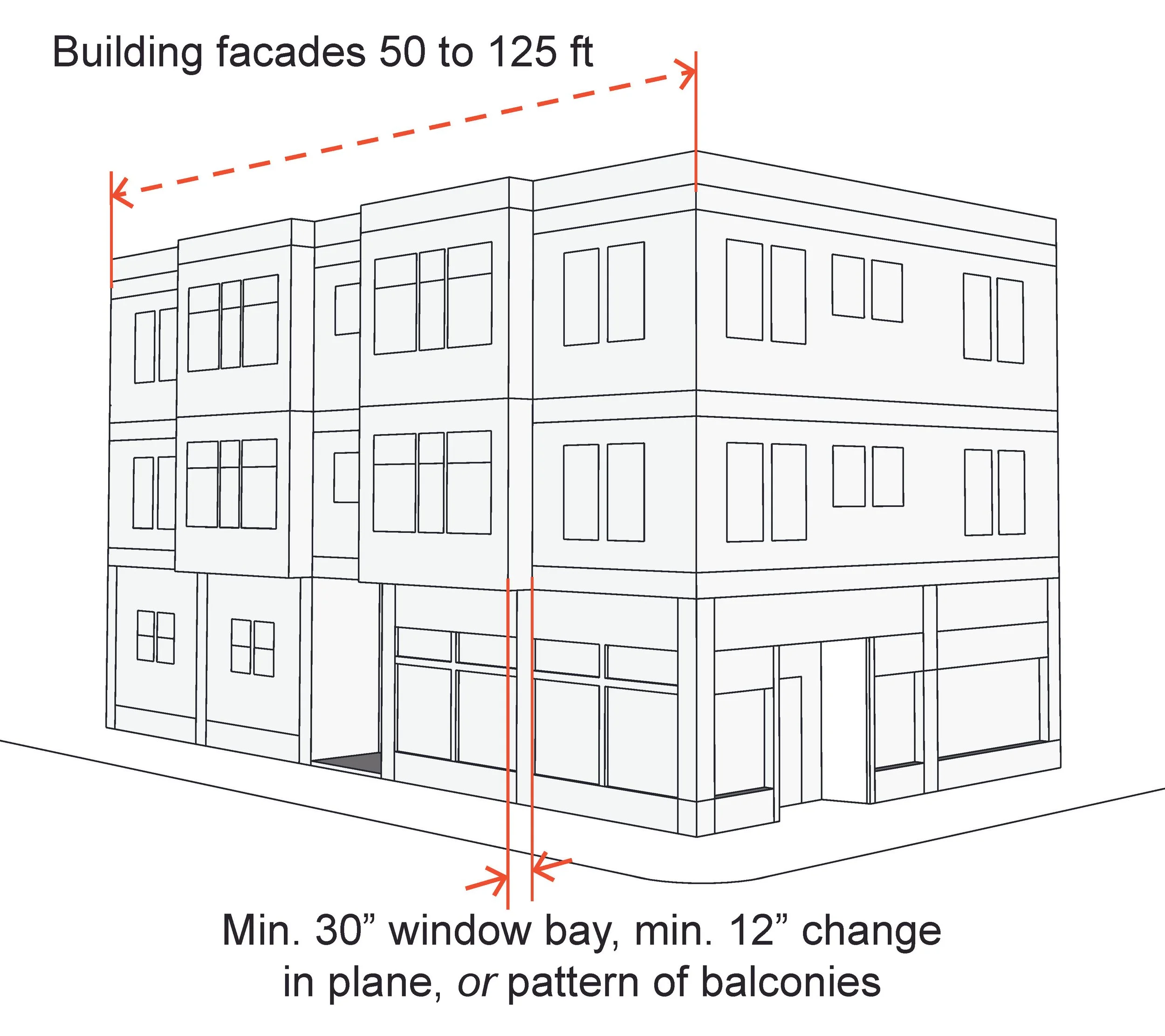

The application of objective standards can address multi-family, single-family, and mixed-use projects and include standards for building placement, articulation, and massing; adjacency and privacy; façade design; landscaping; open space; circulation and access; and other elements of design. Additionally, findings for ministerial approval should be amended to reflect nondiscretionary review.

Figure A: Required Articulation for Building Façades 50 to 125 ft, Image Credit: Lisa Wise Consulting, Inc.

Many California municipalities are adopting objective design standards, a strategy to comply with the State’s Housing Accountability Act, which limits local jurisdictions’ ability to deny or reduce the density of housing developments that meet applicable objective standards. (1)

Woodland, California (Population 60,672; Area Median Income $117,000)

As part of a 2024 Comprehensive Zoning Code Update, the City of Woodland added a robust new chapter to its Code called “Building and Site Design Standards” (Woodland Code, Chapter 17.56). The standards in this chapter support the particular character and intensity of new housing and other development described in the recently-adopted General Plan.

For example, the Small Lot Subdivision Design Standards section provides specific dimensions and configurations for gentle, context-sensitive density that preserves key elements of the existing patterns in the City’s single-family neighborhoods. Specifically, standards for small lot subdivisions require that:

The perimeter setbacks match those of a single-family development.

Exterior unit entrances face the right-of-way.

Interior unit entrances face a common open space or shared drive aisle.

Garage and parking access is from alleys or internal drive aisles.

Detached two-story buildings are a minimum 10 feet apart.

Modified Development Standards

Modifying development standards to accommodate desired housing types and allowed densities is another important and effective approach to accelerating housing production. Standards should be evaluated to identify constraints through feasibility testing, ideally both physically through massing studies and financially through development pro forma analysis. These analyses may identify the need to modify lot size, building height, lot coverage, open space, and parking. Parking amendments are further discussed under Reduced Parking, below.

Lafayette, California (Population 24,808; Area Median Income $155,700)

When the City of Lafayette’s 2024 Housing Element update increased the allowed residential density and added a minimum residential density on specific opportunity sites, the community called for minimizing all other changes to the existing standards. This required detailed site testing to ensure the minimum density could be achieved, identify the “limiting factors,” and avoid unintended constraints. Ultimately, the analysis found that the new densities could be accommodated upon making one or more of the following amendments, depending on the zone:

Increase the maximum floor area ratio (FAR) from a sliding scale based on lot size to a uniform 1.0.

Increase allowed height from 35 to 65 feet.

Increase the maximum lot coverage from 35% to 60%.

Decrease the minimum open space required from 45% to 35%.

Relax the existing upper-story step-back requirements from 50 feet to 20 feet.

The standards were adopted by City Council in December 2024.

Figure B: Zoning Regulations - Push and Pull, Image Credit: Lisa Wise Consulting, Inc. and Cascadia Partners

Diverse Housing Types

Diverse housing types provide greater affordable and equitable housing opportunities. The following examples focus on context-sensitive housing types, such as ADUs and medium density housing, and can effectively enable more affordable and diverse housing opportunities.

California, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs)

Allowing ADUs through ministerial approval and with appropriate zoning standards is becoming commonplace.(2) California law outlining ADU provisions has been frequently amended to strengthen ADU production across the state.(3) Key provisions of California ADU law include:

San Gabriel, CA

Pop. 38,613

AMI $98,200

Achieved 171 ADUs during 2021-2023, an average rate of 57 ADUs per year.

3 ADUs allowed per single-family lot (one attached, one detached, and one Junior ADU)(4)

No minimum lot size required

4-foot side and rear setbacks allowed

No parking required when within ½ mile walking distance of public transit, when part of an existing or proposed structure, or in a historic district; otherwise no more than 1 parking space may be required

Nonconformities are not required to be corrected

Only objective standards may be applied

Ministerial decision must be made within 60-days of application deemed complete

Going beyond ADUs and allowing a broader range of housing types in low-density residential neighborhoods is also growing in popularity. This includes various state-level actions to “eliminate single-family zoning” and more targeted efforts locally for higher-intensity housing in low-density neighborhoods. In these cases, zoning amendments often consist of modifications to land use tables and the development of context-sensitive standards.

Mesa, Arizona (Population 512,523; Area Median Income $101,300)

The City of Mesa, Arizona adopted a form-based code for the downtown area in 2012. The downtown area included some predominately single-family neighborhoods, and the code intended to facilitate the integration of appropriate multifamily housing types into those neighborhoods through the T3 and T4 Neighborhood (T3N and T4N) Zones. In addition to single-unit homes, these zones allow bungalow courts, duplexes, and mansion apartments (a structure with three to six side-by-side and/or stacked dwelling units having the appearance of a medium-sized single-family home). A direct result of these changes was the approval and construction of Mesa Artspace Lofts, which features 50 artist live/work units affordable to households below 60% of area median income as well as 1,450 square feet of ground-floor commercial space, and 2,900 square feet of community space for events, exhibitions, and educational programs.

Mesa Artist Lofts, Image Credit: Dunlap & Magee Property Management Inc.

Reduced Parking

Columbus, OH

Pop. 908,372

AMI $103,300

In 2024, the City of Columbus eliminated parking requirements and modified development standards to increase project feasibility along transit corridors and gained capacity for almost 100,000 new housing units.Lompoc, CA

Pop. 43,610

AMI $119,100

Eliminated residential parking in Old Town Commercial Zone for 5 years (Lompoc Code 17.308.040.E.2).

Reduced parking requirements can incentivize housing production and make new housing more affordable. (5,6) Rightsizing the number of parking spaces aims to establish a requirement that does not exceed what a developer determines necessary; this may be essential to achieve desired housing types (also see Modified Development Standards, above).(7) In recent years, many municipalities have lowered or eliminated parking requirements; and while some of these actions have applied communitywide, most are specific to certain areas.(8)

Since 2023, California prohibits minimum parking requirements for projects within ½ mile of a major transit stop, which includes the intersection of two or more bus routes with service intervals of 20 minutes or less during peak commute periods, with limited exceptions. (9) Additionally, parking requirements for projects with affordable housing are capped at one space per studio/one-bedroom units, 1.5 spaces for two to three-bedroom units, and 2.5 spaces for larger units. (10)

In communities not prepared to embrace reduced parking requirements, a temporary suspension of parking requirements may be appropriate. These may be incorporated into a zoning code or through policy.

South San Francisco, California (Population 64,601; Area Median Income $186,600)

When the City of South San Francisco comprehensively updated its zoning code in 2022, the update incorporated statewide parking requirements and updated ratios for residential uses (South San Francisco Code 20.330.004). Specifically, the updated parking requirements for single-family and multi-family development are based on the number of bedrooms and unit square footage with maximum parking also established for projects located in transit station areas. For example, the following minimum parking ratios apply outside of transit station areas:

2-bedroom single-family residence

1 space per unit (if < 900 sf)

2 spaces per unit (if 900 - 2,500 sf)

2-bedroom multi-family residence

1 space per unit (if < 1,100 sf)

1.5 spaces per unit (if > 1,100 sf)

Conclusion

While zoning is a powerful tool to support housing goals, it cannot alone deliver enough to solve the housing dilemma in the U.S. A mix of factors are necessary for success, many outside of a jurisdiction’s control like market conditions, financing, homebuyer’s purchasing power, and available land. Other factors such as infrastructure and building and fire codes, can also be addressed to help make way for more housing.

In any case, it takes a vision, commitment, and cooperation among City departments, a communicative and trusting relationship between City staff and decision makers, and a plan tailored to the needs and capabilities of each community. One of the building blocks in any such plan would benefit to start with an audit and updates to the zoning code, better enabling diverse housing types, objective and feasible design standards, and reasonable if not reduced or eliminated parking requirements.

References

(1) While the Housing Accountability Act (California Government Code Section 65589.5) has been in effect since 1982, multiple amendments enacted over the last few years have expanded and strengthened its provisions.

(2) Berg, J., & Houseal, J. (February 2023). Practice Gentle Density. American Planning Association, Zoning Practice (Vol. 40, No. 2).

(3) California Government Code Section 66310-66342.

(4) A Junior ADU is a unit of no more than 500 square feet and contained entirely within a single-family residence, and which may share sanitation facilities with the single-family residence.

(5) National League of Cities and American Planning Association (2024). Housing Supply Accelerator Playbook.

(6) Gould, Catie. (April 13, 2023). Parking Reform Legalized Most of the New Homes in Buffalo and Seattle. Sightline Institute.

(7) Also see Overcoming Objections to Zoning Reform: A Primer for Planners (Kimmell, J. & Ness, L., (2021). Western Planner).

(8) Parking Reform Network. Retrieved January 29, 2025, from https://parkingreform.org/resources/mandates-map/

(9) California Government Code Section 65863.2

(10) California Government Code Section 65915

About the Authors

Jennifer Murillo brings 20 years managing complex long-range planning and economic development projects to Lisa Wise Consulting, Inc. She has successfully delivered complex specific plans, master plans, zoning code updates, and housing policy and programs on time and within budget. Jennifer combines an MBA from Indiana University with private sector and public sector experience for a strategic and balanced approach to planning and the economics of land use.

Monica Szydlik brings over 18 years’ experience in planning and urban design to Lisa Wise Consulting Inc. She has focused her career on leading specific plans, housing prototype testing, streetscape design, design guidelines, and zoning code updates. Monica brings a comprehensive approach that combines technical urban planning, an expertise in architecture and design, and a focus on feasibility. She holds a Master of Architecture from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.