Bling or Bust Assets: Case Studies in Rural Capital Asset Management

By Paul Moberly, AICP and Kyle Slaughter

Capital assets are a community’s built and high-cost assets (e.g., roads, pipelines, sewage facilities, buildings, parks, arenas, recreation facilities, sheds, and vehicles). Community leaders are responsible for the management of these public assets—they require planning to develop, significant resources to install, and good management and upkeep to ensure services, financial stability, and limit emergencies. Conversely, issues arise when communities fail to keep updated inventory of their assets, overbuild or build without considering regional amenities, and neglect to consider or underestimate operations and maintenance costs. This article presents examples to illustrate some of the pitfalls in trying to manage capital assets and provides suggestions for rural towns.

Amenity or Liability?

One rural community wanted a new community swimming pool. The old one was a rundown outdoor pool, and a nearby “rival” community had recently built a high-end aquatic center. The public clamored for an improved facility for years. The local elementary school ran a penny drive and collected a few jars full. The city received a $4 million mix of state grant and loan, and proceeded to build a very attractive aquatic center—as nice a facility as one in any affluent suburb.

While the town was planning to build this project, a powerful economic downturn caused this town of around 6000 to run a $230,000 deficit. Public budgets were cut significantly with accompanying layoffs. However, with deference to the community’s desire, the pool was still built. Financially, in the middle of a budget crisis, the town went from a pool which funded 60% of its operations through fees and ran a $45,000 operations deficit, to a pool which was 40% funded with fees and ran a $340,000 operations deficit (including debt relief on a 20 year loan).

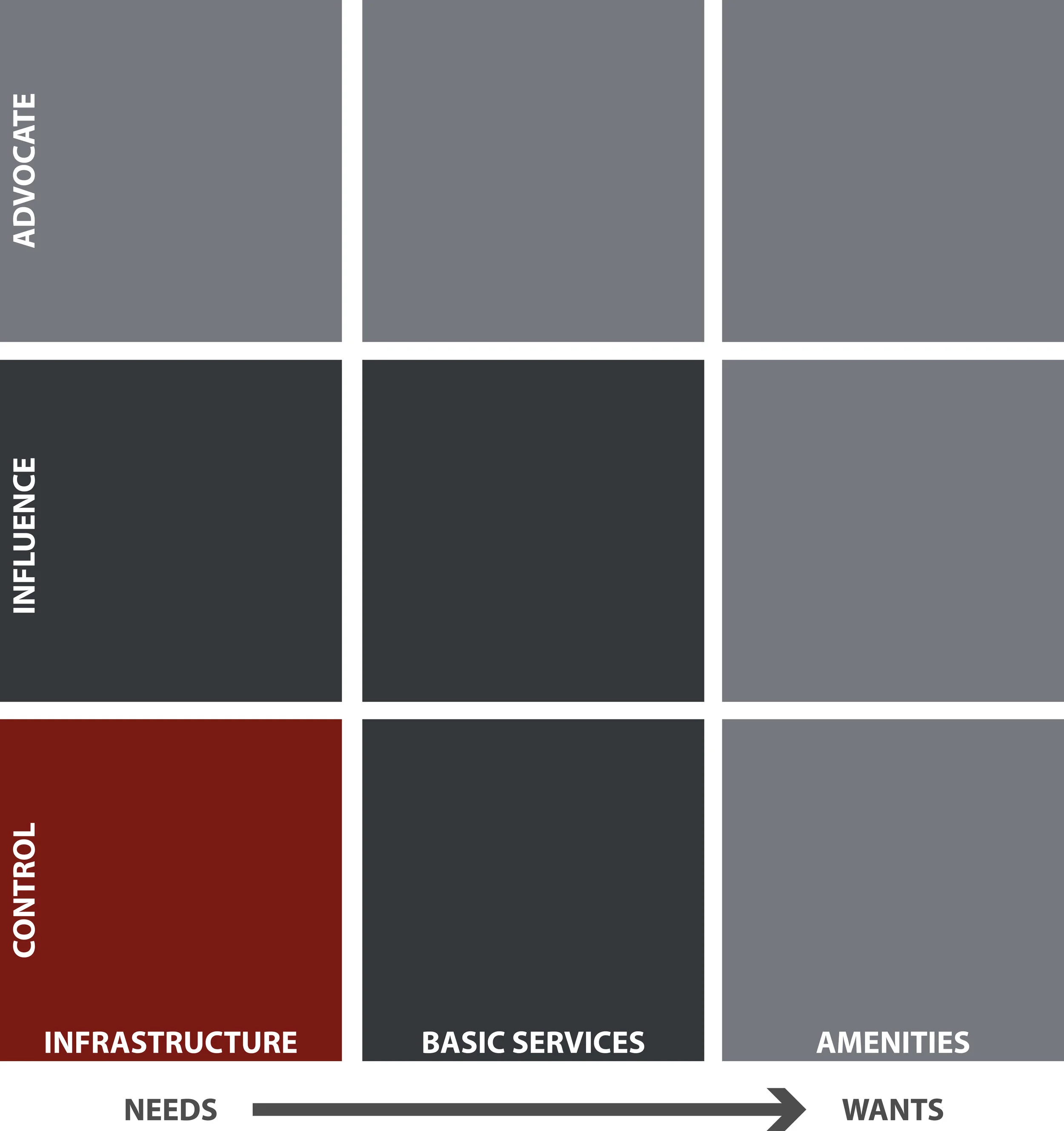

Prioritize critical needs first. Focus your finite resources on actions and projects that the town has direct control over and which are essential to the community. Amenities and policies that affect community life are important, yet a lack of control over outcomes would make these a lower priority.

While a community may be willing to pay for a deficit on an amenity they greatly desire, it is critical for that decision to be made with all the financial implications being clear to leaders and the public. Otherwise, nice amenities can become a bait-and-switch for public resources, appearing to create community even as they hollow out town coffers. Many arguments can be made for why this pool should or should not have been built, but during a time of fiscal distress, the town chose to increase their spending on a budget liability. One of the most difficult responsibilities of civic leadership is to make difficult decisions about public funds. Leaders must be able to make these tough decisions with the full financial picture in mind, prioritizing essential needs while balancing community quality of life of those things in the control of the community.

Often leaders wonder how to make these challenging decisions in the face of significant public pressure. Creating a well-established, publicly adopted, capital facility planning process can help reduce leaders’ feeling that they must simply act with or against the public sentiment. This should identify responsible parties, timelines, and criteria for prioritizing maintenance, repairs, and new projects. Developing this plan independent of any specific crisis or decision can help avoid pet projects, political maneuvering, and will better facilitate fact-based decision making. To be effective, leaders must feel confident they understand and are committed to following their community’s capital improvement planning process and policy. It won’t eliminate difficult decisions, but it does provide a stronger rationale for making them.1

You Can’t Always Afford Free

Another similar example happened in a small isolated town that wanted an upgraded pool. They also received a $2.5 million mix of state grant and loan and built a more modest, but very modern and attractive indoor swimming facility. The town felt like they were getting an amazing deal to acquire such a low-cost amenity. However, after building it, they realized the costs of operating a pool were far greater than the projected use. While the public supported the project, local attendance wasn’t enough to support its operation. The facility is currently closed for nine months of the year and has limited hours during the summer when it is open. As a result, the facility only covers 20% of its operating costs through fees as a new facility; their ability to cover costs will decrease further as maintenance costs increase with the facility’s age. While many city recreational facilities operate at a loss, this facility is a significant fiscal liability for a small community with limited resources.

Swimming facilities and other recreational amenities can greatly increase the quality of life for local residents and can help encourage tourism, but can also be very costly to maintain and operate. Thinking regionally about such assets can help decrease their fiscal impacts.

The purpose here isn’t to necessarily say either of these swimming facilities were a bad idea, nor that these expenditures didn’t increase the local quality of life. They are not good investments in any traditional sense, but they are nice amenities. The language we use—capital assets, public amenities, capital improvements—inherently implies positive development, however, building these facilities is not always a net positive for communities. These true stories offer far-too-common examples of small town capital improvements planning errors.

While grants or low-interest loans are tempting—many communities struggle to find funding for projects—too few communities deeply examine the full costs of ownership of potential amenities. Most of the stories in this article have one element in common: relatively easy government money. While grants and low-interest loans play a fundamental role in rural community finance, they can be a double-edged sword if towns aren’t careful to scale to their needs and don’t fully and realistically examine operations, maintenance, and eventual replacement costs.

The following process may help with identifying true costs of ownership when examining future built amenities:

Contact other communities and review what costs they’ve had with their asset.

Document and aggregate the data.

Evaluate the data by assessing similarities between your proposed project and the comparable projects you assessed.

Using the data, develop a most likely high and low operations and maintenance cost estimate.

Clearly present the scenarios and project viability to elected leaders.

Elected leaders should inform the public of the operations and maintenance costs and the potential subsidies the community may have to provide.

After gathering public input, leaders should decide whether to construct the asset 2.

While this type of upfront analysis can be time consuming, strong analysis can help community leaders fully prepare for the costs of an asset’s ownership, scale down an overbuilt project, or just pass on a possible grant—and make their town more fiscally viable in the process.

Watch Your Assets

It can be difficult to keep track of town assets and their status, but two towns learned the hard way that forgetting to inventory capital improvements is a costly omission. A town wanted to expand their water supply access and received an almost million dollar state grant for a new pump. As time went by, due to a lack of maintenance and accounting for the area’s unique water chemistry, the pump seized up and has sat broken and idle in the 15 years since. In another town of 2,000 people, a sewer pipe failed and water pipes had deteriorated in multiple locations on Main Street. According to one analyst, this was caused by a general unwillingness to raise taxes or fees to cover preventative maintenance. After nearly $23 million later in state low interest loans and grants—and finally raising taxes and fees to help cover repair and replacement costs—the town has finally rebuilt the main stretch of system, while crippling their financial standing in the process.

Do not wait until assets break down to replace them. Regular maintenance is less expensive and disruptive than infrastructure failure.

Since it is usually several feet underground, it can be difficult to keep an eye on water and sewer infrastructure. According to a recent comprehensive study completed by Utah State University of water system utilities,3 each year over 240,000 water pipes burst in the United States and water main break rates have increased 27% during the past six years. Looking ahead, these breaks will likely continue: 28% of water mains are over 50 years old and the average age for a failing pipe is 50 years. As the researchers pointed out, a greater challenge exists for rural utilities, with lower density development equating to more miles of pipe per connection, fewer technical and financial resources, and a smaller customer base to absorb costs. Only 45% of utilities conduct some type of assessment on their water mains, and while the research didn’t isolate rural data specifically, the assessment rate is likely much lower in rural areas with constrained resources.5

Getting ahead of problems requires that community leaders institutionalize knowledge of existing capital assets and their condition, and create a system for prioritizing asset projects and funding. Documenting existing assets is essential to asset management, but many small communities still fail to compile the needed data and instead rely on hearsay, expensive emergencies (when the water line breaks, we’ll know it’s time to fix it), and the memory of long-term public works employees. Capital asset inventories identify existing assets’ location, current condition, needed repairs, and replacement timelines. This inventory should contains a timeline of expected expenses that leaders can save funds towards; conversely, it identifies assets that can be retired to free up funds for other projects. This inventory should be updated as changes to the condition of an asset occur (e.g., repair work done, major storm damage, etc.) and repeated as needed.4 Engineering firms may be required to help complete assessment of some infrastructure, but the cost savings from proper maintenance enabled by such information outweighs the cleanup of major infrastructure failure.

This example also illustrates that while no one wants to raise taxes or rates, particularly within the generally intimate community that exists in rural towns, part of a capital improvement planning process must be examining use rates and taxes to ensure long-term viability, encourage incremental adjustments, and avoid large disrupting tax or rate increases. Evidence of the challenges that exist for communities who wait to raise taxes until the circumstances are dire abound.

Think Regionally, Act Regionally

Like many rural communities without a single employed firefighter, several towns in a region struggled to maintain enough volunteer firefighters to service their areas. Notwithstanding, due in part to the availability of grant and low-interest loans, engineering firms upsold multiple towns on large new fire stations. As each saw the other had a new fire station, an element of regional competition emerged, stoked by private consultant interests, with one town of less than 1,500 people building a five-bay fire station (the third of such size in the region) just over 3 miles from a neighboring town’s four-bay station. The proliferation of fire stations resulted in a 51% overlap in the regional service area, not including their exaggerated size. Afterward, several communities couldn’t afford to buy multiple fire trucks, and they either acquired loan or grant money to purchase the trucks, or many bays were used as impromptu gyms, car repair stalls, town meeting space, long-term storage, or just sat empty.

It’s wise to prepare assets for future use, but resist the tendency, even with government grants or low-interest loans, to build bigger or fancier than your town’s real requirements.

One solution to the lack of regional coordination—and consequently the solution this region adopted—is to form a special service district to organize regional infrastructure purchases and maintenance. Their special service district manages water, sewer, and roadways for multiple towns in the region. They benefit from pooled resources, strengthened grant applications, and decreased administrative burdens on local leaders. This special service district receives annual, prioritized capital repair and improvement lists from member towns, and after examining overall system needs, it applies available funds. The board is composed of elected officials from each community, ensuring that each community receives fair treatment. They have developed a fiscally sound debt repayment structure that ensures there is sufficient funds to cover improvements, replacement, and construction costs while maintaining an appropriate debt-to-revenue balance.5 State funding sources like to lend and grant to this SSD because it can demonstrate clearly how and why it prioritized its investments as it has. While special service districts won’t work in all circumstances, it can be a powerful mechanism for regional efficiency.

Keep Your Grasp Within Your Reach

When decisions are made on a case-by-case basis, and not part of an overall awareness for the “big picture,” towns can end up overextending themselves. For example, one town of 7,500 needed special state funding of $4 million for basic road maintenance. Although the town receives nearly $400,000 in state road funds per year, with over 50 miles of paved road to maintain, they fell behind in maintenance. The big fiscal shot in the arm will hopefully enable them to catch up on essential maintenance; however, if the town’s practices don’t change they will remain fiscally dependent on the state to “award” their road maintenance. This type of fiscal reliance on government subsidy is precarious and typically flies in the face of the values espoused by rural leaders and communities, and yet without significant changes to current practices, that reliance will remain.

Charles Marohn of Strong Towns continues to advocate for more responsible infrastructure development. One argument he makes for rural towns is that the public costs for connecting long lengths of roads and pipe to far-dispersed homes will rarely be covered by the service fees, connection fees, or property taxes of the connected homes during the lifespan of the infrastructure.6 That deficit will require continual subsidy from elsewhere, either through the general fund, debt, other new development, or external grants.

Towns can mitigate or avoid some of these problems by having a strong, usable general plan and by developing supporting policies for annexation, development review, and zoning ordinances. Consider that not all roads need to be paved, and not all houses need to be connected to sewer. Examine how your community cross-subsidizes different development or amenities. Be careful to not just grow for growth’s sake, nor simply annex areas because the property is adjacent or even service dependent. Depending on rate structures, often the additional tax revenue doesn’t offset the costs.

As the examples included here show, most communities want the best amenities they can get, whether it’s swimming pools, fire stations, pipes or paved roads. When community leaders represent their constituents, they take upon them the challenging responsibility to make the best decisions they can for the long-term health, safety and well-being of the community. These goals aren’t always aligned. Having a strong capital asset planning and management process can help provide the data and structure needed to make those tough decisions become the best-made decisions.

For more information on these topics visit these resources online:

StrongTowns.org.

Utah Community Development Office Materials:

Capital Improvement Planning: An Introduction for Local Leaders. http://ruralplanning.org/assets/capital-improvement-planning-web.pdf

O&M: Operations and Maintenance Costs and Considerations. http://ruralplanning.org/assets/operations-and-maintenance---web.pdf

Capital Asset Inventory: Helping Community Leaders Learn What’s Under Their Feet. http://www.ruralplanning.org/assets/capital-asset-inventories-final(web).pdf

WORKS CITED

1 Utah Community Development Office. 2017. “Capital Improvement Planning: An Introduction for Local Leaders.” http://ruralplanning.org/assets/capital-improvement-planning-web.pdf

2 Utah Community Development Office. 2016. “O&M: Operations and Maintenance Costs and Considerations.” http://ruralplanning.org/assets/operations-and-maintenance---web.pdf

3 Folkman, Steven, 2018. "Water Main Break Rates In the USA and Canada: A Comprehensive Study" (2018). Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Faculty Publications. Paper 174. Utah State University. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mae_facpub/174

4 Utah Community Development Office. 2016. “Capital Asset Inventory: Helping Community Leaders Learn What’s Under Their Feet.” http://www.ruralplanning.org/assets/capital-asset-inventories-final(web).pdf

5 Utah Community Development Office. 2016. “Zero-Growth Planning: Empowering Rural Communities in Decline.” http://ruralplanning.org/assets/zero-growth-paper-lq.pdf

6 Marohn, Charles. 2009. “The Cost of Development, One Example.” StrongTowns.org. March 30, 2009. https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2009/3/30/the-cost-of-development-one-example.html

About the Authors: Paul Moberly, AICP, is the Editor of the Western Planner and a Community Development Specialist with Utah's Community Development Office, part of Utah Housing and Community Development. With a background in international business and marketing communications, Paul focuses on community and economic development, quantitative data analysis and community design. A long-time student of rural issues, he's consulted with rural towns throughout upstate New York, the Adirondacks, and Utah and has studied rural decline during the past decade throughout the Northeast and Northwest. He holds a Masters in Regional Planning from Cornell University, and a community development-focused Masters in Education from Boise State University.

Kyle Slaughter is currently in administration at Brigham Young University, and was formerly a community development consultant with Utah’s Community Development Office. He has a background in consulting, survey design, and data analysis. He’s worked with communities throughout Utah on planning and town management. He holds a Masters of Public Administration from Brigham Young University.