Conflicts Abound: How Future Development Threatens Critical Migratory Bird Habitat Along Utah's Wasatch Front

by Aubin Douglas

A growing population and an ecological gem

The Wasatch Front is a north-to-south urbanizing corridor, sandwiched between two natural features: the Wasatch Mountain Range and the Great Salt Lake (GSL). The GSL and its wetlands provide a multitude of ecosystem services for the surrounding population, including water quality improvement, snow generation for recreation, and brine shrimp production for industry which, incidentally, contributes one third to one half of the world’s supply of brine shrimp. The GSL also supports millions of migratory birds annually, and is considered North America’s single most important interior wetland for birds by the National Audubon Society.

Figure 1: A black-crowned night heron standing in water at the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge on the GSL. Photo credit: Gary Witt.

With unique natural amenities in every direction, it is no wonder the Wasatch Front is an attractive place to live. In fact, the Wasatch Front is the most populated area in Utah. Utah itself consistently has one of the highest population growth rates in the U.S., with the majority of that growth occurring along the Wasatch Front. There is no indication that this pattern of increased growth will subside anytime soon, as the state’s population is predicted to double by 2065. The government of Utah is actively seeking ways to support this growing human population through incentive programs to draw new businesses to the Wasatch Front and by expanding infrastructure and (sub)urban development projects throughout the region. Inevitably, agricultural lands that buffer GSL wetlands from urban areas are prime targets for developers since they are located on private land, are typically near developed areas with supporting infrastructure, and may even hold water rights.

Unfortunately, the agricultural land and open space along the eastern edge of the GSL provide critical spillover habitat for millions of migratory birds. Both developers and conservationists are striving to understand potential conflicts between these two, opposing land uses in the wildland-urban interface as the population continues to expand.

Figure 2: The study area for this research is indicated by the white box that encompasses Salt Lake City and Farmington Bay of the GSL. Map created by Aubin Douglas.

Background on the study

This study was completed to fulfill the research requirements for my MS in Bioregional Planning degree at Utah State University. Bioregional Planning (BRP) explores how human settlement and cultures influence a landscape’s biophysical systems and, in turn, how a region’s biophysical system influences human settlement and culture. The inherent reciprocal nature of a BRP study provides a solid basis for generating alternative land use plans and creating baseline assessments for areas that are either potentially vulnerable to or suitable for different land uses within a region.

Through my studies at USU, I came to understand how important the GSL was to migratory bird populations in the Western Hemisphere. I also discovered several large proposed development projects along the Wasatch Front. Out of curiosity, I searched for in-depth studies on how these projects would impact our major migratory bird hub, and was left wanting. While any large development project is required to perform an environmental impact assessment (EIA) or statement (EIS) (especially where wetlands are concerned), I did not find enough research to answer my questions or alleviate my concerns about possible impacts to bird habitat. For my graduate thesis, I decided to answer my own questions as best as I could with a limited budget while using the scientific method. I wanted this research to be transparent, easily reproducible, and based on existing data from authoritative agencies and sources.

Identifying conflicts

The ultimate goal of this research was to identify potential conflict areas between three proposed major development projects and the current migratory bird habitat of the GSL environs, specifically around Farmington Bay which is the southeast corner of the lake. To assess potential land use conflicts between current migratory bird habitat and future development, I first selected 15 migratory bird species that were representative of the three major wetland bird guilds (i.e., shorebirds, waterbirds, and waterfowl) that depend on the GSL. As over 250 bird species use the area, it was pertinent to use a smaller subset of representative species for data management, simplicity, and replicability purposes. The 15 species were selected with the help of local ornithologists and other experts from Utah State University, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, the National Audubon Society, Friends of the GSL, and the Intermountain West Joint Venture.

After selecting the representative species, habitat data for all 15 species were obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Gap Analysis Program (GAP) species data portal. Habitat maps for all 15 species were created, which covered all three guilds. The guild habitat distributions were generated by combining the habitat data for the five representative species within each guild. For example, the habitat distributions for the snowy plover, American avocet, long-billed curlew, willet, and Wilson’s phalarope were combined to create the shorebird guild habitat distribution.

Figure 3: Mapped habitats of all 15 representative migratory bird species (includes shorebirds, waterbirds, and waterfowl). Areas with the greatest amount of species overlap are the darkest blue. Map created by Aubin Douglas using USGS GAP data.

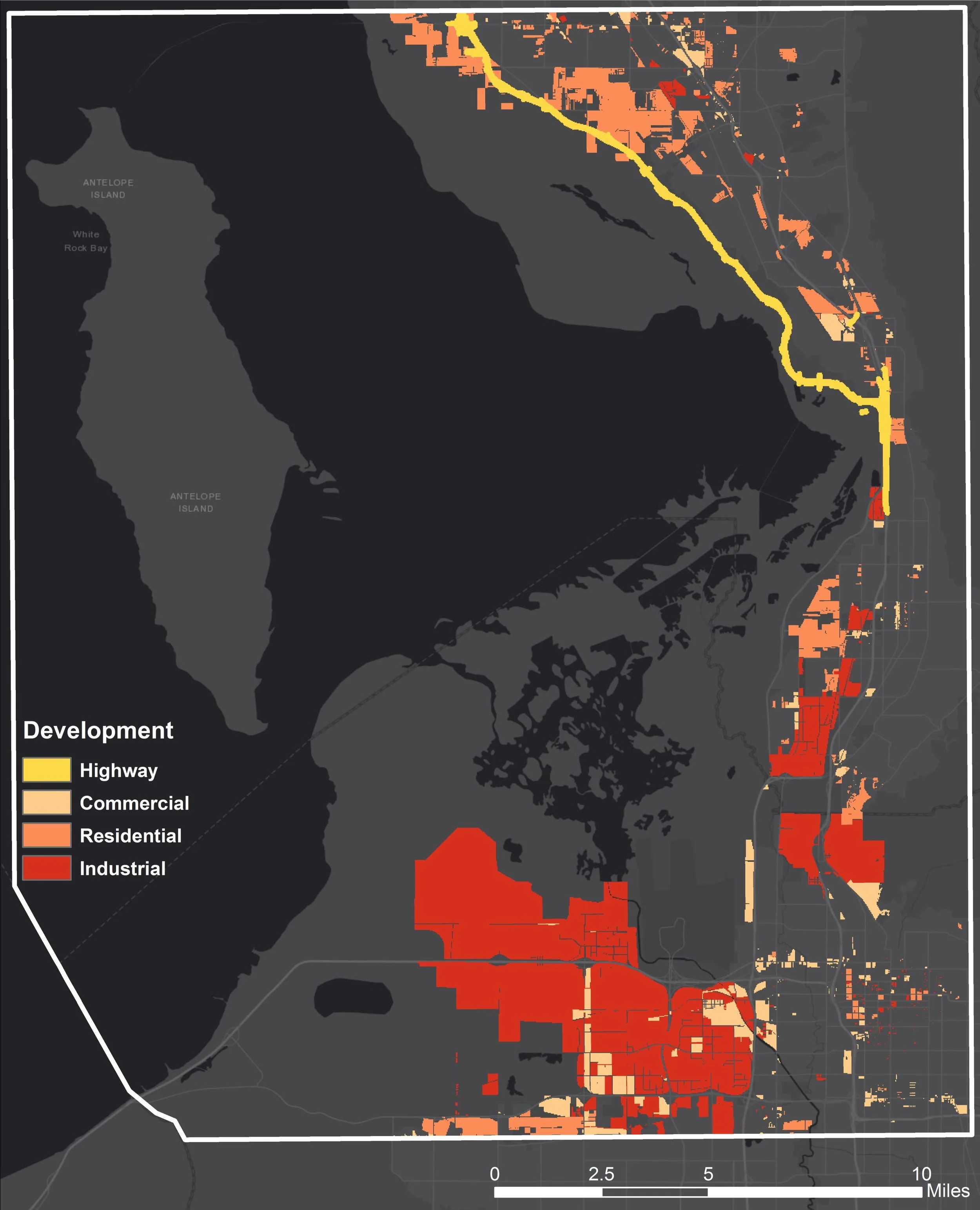

After developing the spatial habitat data for all three bird guilds, I researched and selected three proposed development projects that fell within the study area. The projects selected are currently three of the largest proposed developments surrounding Farmington Bay of the GSL. The first project is the West Davis Corridor, which is a 19-mile long highway to be constructed along the eastern edge of Farmington Bay. The second project is the Northwest Quadrant development, which is slated to become the location of a new inland port and new state prison, just south of Farmington Bay. The third and final project I assessed was the Wasatch Choice 2040 Regional Vision, which is a regional development plan for the Wasatch Front out to 2040; it is considered a “best-case scenario” for sustainable development along the Wasatch Front that will support the expected human population growth. The planning and zoning data were simplified for each project into four major development categories: residential, commercial, industrial, and highway. This way, I could determine the development types that are expected to generate the most conflict with current habitat.

Figure 4: A map showing the footprints of all three proposed development projects. The footprints are broken down into four categories of development types: highway, commercial, residential, and industrial. Map created by Aubin Douglas.

Once the spatial data for both the development projects and migratory bird habitats were mapped, I performed a simple conflict assessment by overlaying the datasets in ArcMap (TM). First, isolated areas of overlap between development and habitat were identified. Then I uesd a data analysis platform, RStudio®, to assess and analyze the conflict between each guild/species and project/development type.

The data don’t lie

Based on the USGS National GAP habitat data, a substantial amount of bird habitat occurs within the study area. Shorebird, waterbird, and waterfowl habitats respectively covered 31%, 76%, and 63% of the study area. Spillover habitats occur in and around urban areas along the Wasatch Front. Agricultural lands, open spaces, parks, and ponds play an important role in maintaining the carrying capacity of the region for the millions of migratory birds that visit every year.

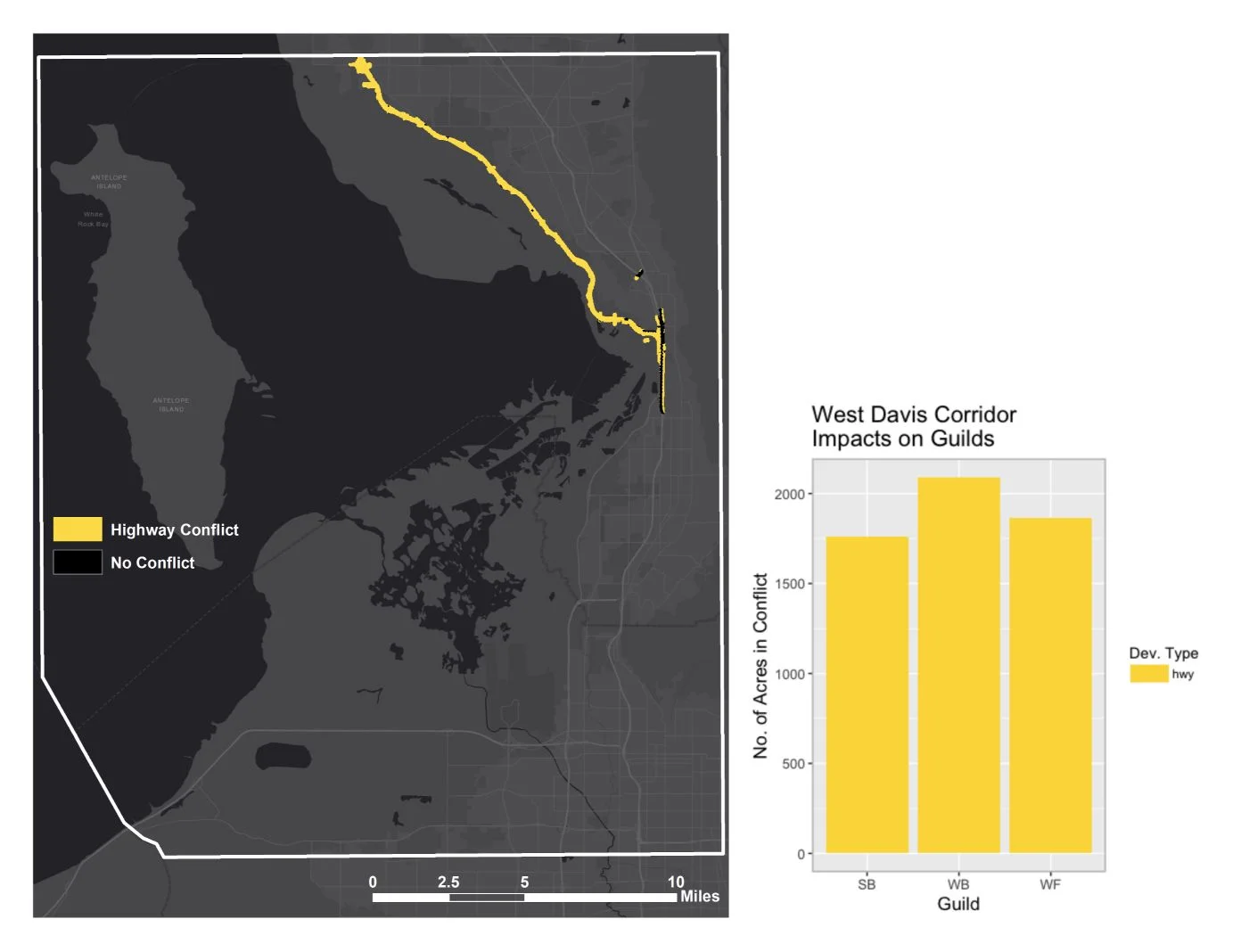

Each of the three assessed development projects are in conflict with thousands of acres of habitat in the area. For example, the West Davis Corridor project is predicted to generate 2,090 conflict acres, which constitutes 88% of this project’s total footprint.

Figure 5: The yellow area on the map indicates areas of conflict with bird habitat – 88% of this project’s footprint is in conflict. This entire project is the ‘highway’ development type. The graph depicts the number of acres of conflict with each bird guild that is associated with this project. Waterbirds are the most impacted, followed by waterfowl and then shorebirds. Map and graph created by Aubin Douglas using data from the Utah Department of Transportation and USGS GAP data.

The Northwest Quadrant project is expected to generate 4,527 conflict acres, which constitutes nearly 30% of this project’s total footprint.

Figure 6: The red and beige areas on the map indicate conflict with bird habitat – 30% of this project’s footprint is in conflict. This project is both industrial (red) and commercial (beige) in nature. Industrial development is by far the more disruptive development type for this project. The graph depicts the number of acres of conflict with each bird guild per development type. Waterbirds are the most impacted, followed by shorebirds and then waterfowl. Map and graph created by Aubin Douglas using data from the GIS Department of Salt Lake City and USGS GAP data.

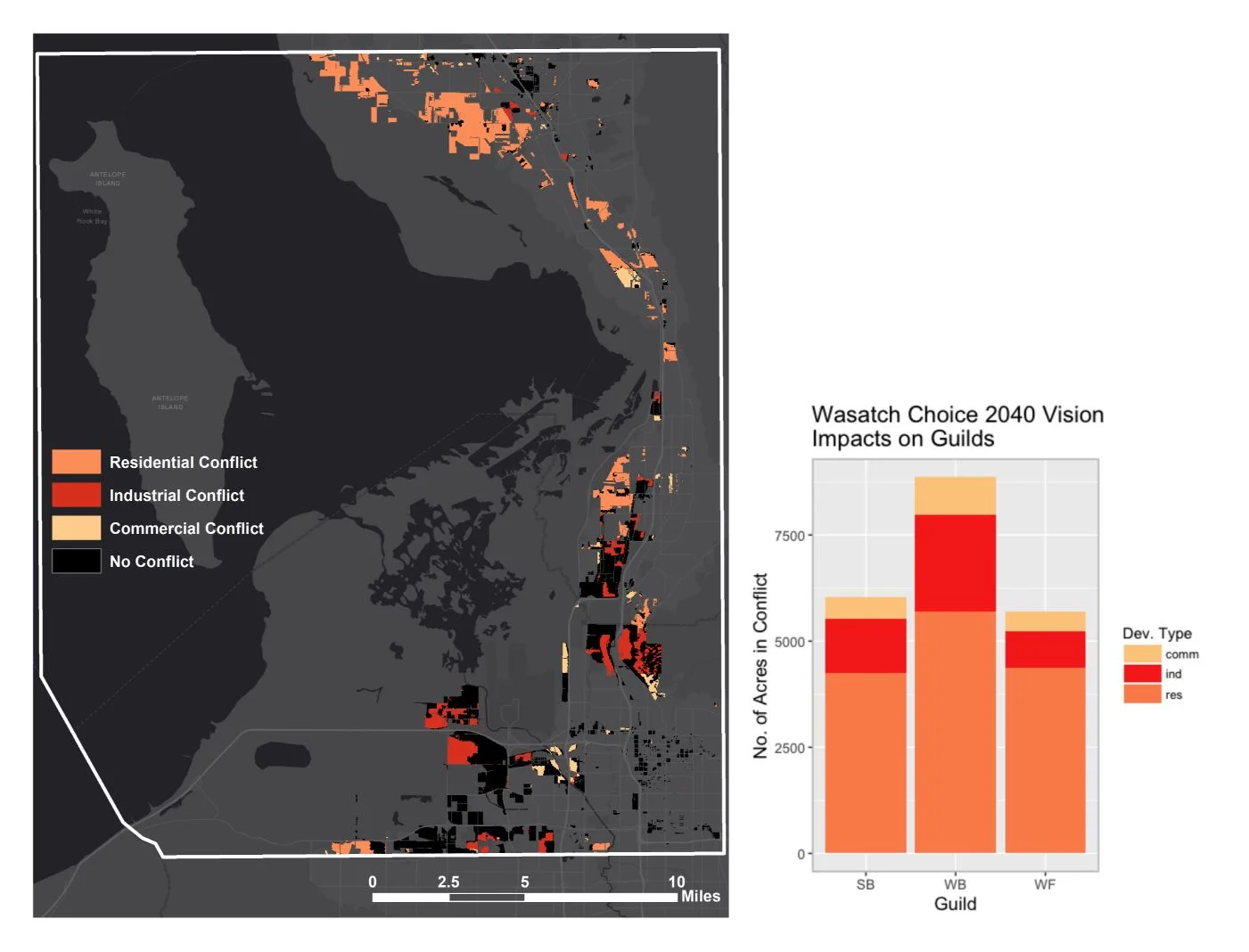

The Wasatch Choice 2040 Regional Vision project is expected to generate 8,980 conflict acres, which constitutes nearly 50% of this project’s total footprint.

Figure 7: The orange, red, and beige areas on the map indicate conflict with bird habitat – 50% of this project’s footprint is in conflict. This project is residential (orange), industrial (red), and commercial (beige) in nature. Residential development is by far the most disruptive development type for this project, followed by industrial development, and then commercial development. The graph depicts the number of acres of conflict with each bird guild per development type. Waterbirds are the most impacted, followed by shorebirds and then waterfowl. Map and graph created by Aubin Douglas using data from the Wasatch Front Regional Council and USGS GAP data.

Results of the spatial conflict analysis indicate that the most impacted guild will be the waterbird guild, followed by the shorebird guild and the waterfowl guild. However, when the conflict analysis for each of the 15 representative bird species was performed, three species were disproportionately impacted by all three projects—the white-faced ibis (waterbird guild), the willet (shorebird guild), and the northern pintail (waterfowl guild). Surprisingly, each of the birds are from a different guild, meaning no guild will be unaffected by habitat loss if these projects continue as planned.

Recommendations for planners and stakeholders

While it is important to maintain migratory bird habitat in the region, it is infeasible to recommend that no new development occur due to the future needs of the expanding human population along the Wasatch Front. However, it is reasonable to avoid developing areas that are habitat hotspots, i.e., spaces where four or more of the representative species’ habitats overlap. If developers and planners spared these areas, over 6,300 acres of the most critical habitat would be saved within the study area. Here, I outline a few actionable recommendations for planners and developers to accomplish this.

First, continue promoting ‘centered growth’ along the Wasatch Front. Centered growth is the cornerstone of the Wasatch Choice 2040 Regional Vision, which is focused on creating more sustainable, walkable communities by 2040. By reducing the amount of urban sprawl, more open space and agricultural lands can be spared for both people and birds. Through extensive public surveys, Envision Utah has found that Utahns value their agricultural heritage and wish to see it maintained into the future. Centered growth also promotes land recycling, which involves using and redeveloping old infrastructure within an already developed area. Centered growth also includes creating more densely-populated neighborhoods, and increasing mixed-use developments so people can walk or bike to their jobs, the store, their bank, or other places instead of needing to drive.

The second step is closely related to the first step: maintain and protect ‘the fringe.’ The fringe consists of the areas of open space and agricultural land along the eastern and southern edges of the GSL. Much of this land is agricultural, so Transfer of Development Rights would be applicable to allow greater in-fill in the urban areas (increasing density) while maintaining the crucial agricultural land and open space that buffers the wetlands, and provides greater quality of life to local residents. Unfortunately, much of the area south of Farmington Bay is slated for development in the Northwest Quadrant project. If this area becomes the site of the planned inland port, even greater negative impacts on bird habitat can be expected through increased impermeable surfaces, greater noise, light, and air pollution, and more avian-window collisions. These types of negative impacts can and should be lessened through bird-friendly landscape and building policies and practices such as window treatments, landscaping with native vegetation, and light and noise restrictions.

The third and final recommendation is to reconsider the location or the entire development of the West Davis Corridor. While this seems idealistic, the majority of this project’s footprint is in conflict with bird habitat (88%), and over 67% of the footprint is in conflict with habitat hotspots (i.e., areas where four or more habitats of the representative species overlap). Due to the impacts on wetlands, the Utah Department of Transportation is expected to mitigate some of the ecological damages of this project through adding roughly 1,000 acres to the nearby Farmington Bay Waterfowl Management Area and The Great Salt Lake Shorelands Preserve. However, the majority of wetlands along the eastern edge of Farmington Bay will likely be impacted by this highway due to the increased noise, light, water, and air pollution that accompany all major highways. Due to the effects of induced demand (i.e., “if you build it, they will come”), there will likely be more motorists on the roads in the future because of this new highway. The West Davis Corridor project sends a message to Wasatch Front residents that driving is still the preferred mode of transportation. Instead, I recommend that the funds appropriated for this project be reallocated to improving (and promoting) public transit and sustainable development within the region, or that greater funding is put towards protecting more of the GSL’s wetlands from future development.

These recommendations have the added benefit of reducing the number of cars on the road, and thereby aiding the Wasatch Front in the battle against increasingly poor air quality, which many Utahns name as their biggest concern for the region. Most of the Wasatch Front is a nonattainment region for particulate matter and ozone levels, meaning the Environmental Protection Agency considers it a health hazard that must be mitigated in the near future. By following these recommendations, Utahns would have improved air quality, the conflict generated by the projects assessed in this study would be considerably reduced, and current habitat would continue to support millions of migratory birds within this booming region for future generations of both birds and people.

Figure 8: A white-faced ibis in a wet meadow near Farmington Bay. This is a species of ‘greatest conservation concern’ for the state of Utah and is by far the most impacted species in terms of habitat loss for all three proposed projects in this study. Photo credit: Gary Witt.

For further reading, see the executive summary or the full report of this research and findings (both are linked in the “Suggested Resources” section).

About the author

Aubin Douglas received a BA in Environmental Studies from the University of Colorado and completed her MS in Bioregional Planning in 2018. She is working toward completing a second MS in Ecology through Watershed Sciences at Utah State University.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by the many stakeholders involved in the area, as well as my research committee. This article was edited by Dr. Keith Christensen and Dr. Karin M. Kettenring. Keith Christensen is an Associate Professor at Utah State University in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning. Keith's work emphasizes macro-level environmental factors and spatial processes on communities. Dr. Karin Kettenring is an Associate Professor at Utah State University in the Department of Watershed Sciences and the Ecology Center. Her research and teaching focus on wetland ecology, management, and restoration.

Suggested Resources

Link to the Envision Utah Survey Results:

https://www.envisionutah.org/projects/your-utah-your-future/item/346-results

Link to the USGS National GAP species data portal:

https://gapanalysis.usgs.gov/species/

Link to a free download of the executive summary:

https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/laep_stures/1

Link to a free download of the full report:

https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/1322/