2014 Boles Fire leads to first rural resilience planning process in the nation

The City of Weed is a tiny historic lumber town nestled at the base of Mount Shasta in California. Photo by Tom Brandeberry

The 2014 Boles Fire went through Weed, California destroying 16 percent of their housing and other structures. A year later, the community started a planning process, called the Weed Resilience Plan, which was completed in April 2016. This effort was the first example of a rural resilience planning process in the nation.

by Tom Brandeberry

A fire destroys a small, rural town

On Sept. 15, 2014, a homeless man, later charged and convicted of arson, started a fire behind the Boles Creek Apartments in the central part of the City of Weed, a tiny historic lumber town nestled at the base of Mount Shasta. That fire quickly became a fast-moving inferno. About 120 minutes later, the fire destroyed or damaged 157 buildings, homes, library, churches, and the community center, along with more than 375 acres. The fire partially damaged the one of the larger employers, Roseburg Forest Products mill, displacing some 60 workers while leaving almost one third of the town's property owners and renters alike without a house to go home to. California’s Governor Edmund G. Brown soon declared the Boles Fire in the City of Weed a disaster.

Located 49-miles south of the California-Oregon border, Weed gets its name from the founder of the local lumber mill Abner Weed who discovered that the area's strong winds were helpful in drying lumber. By the 1940's Weed boasted the world's largest sawmill, and about 20 years later this company town became incorporated. Surrounded by natural beauty and many outdoor recreation opportunities, this once lumber town has been transitioning into a tourist destination and is part of the Volcanic Scenic Byway, a 500 mile route beginning in California’s Lake Amador basin and ending at Crater Lake in Oregon. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, the total population of Weed is 2,967 but increases to 6,318 when counting the adjacent communities that use Weed's zip code. These communities include the unincorporated town of Edgewood, the Weed Airport, the Hammond Ranch subdivision, the Hidden Meadows subdivision, and numerous residential and agricultural properties situated throughout the unincorporated area.

The city created a Weed Long-Term Recovery Group, dedicated to much of the immediate needs of the community and efforts to rebuild the damaged parts of town. Meanwhile, the city also created the City of Weed Resilience Team, which focused on building the resilience plan. The Resilience Team included the city administrator, finance director, Retired CDBG Section Chief, Siskiyou County Community Development Director, Siskiyou County Deputy Director of Planning, Great Northern Services (a community nonprofit) Executive Director, Mayor Weed City Council, City of Weed Planning Commission, and Siskiyou County Board of Supervisors representative.

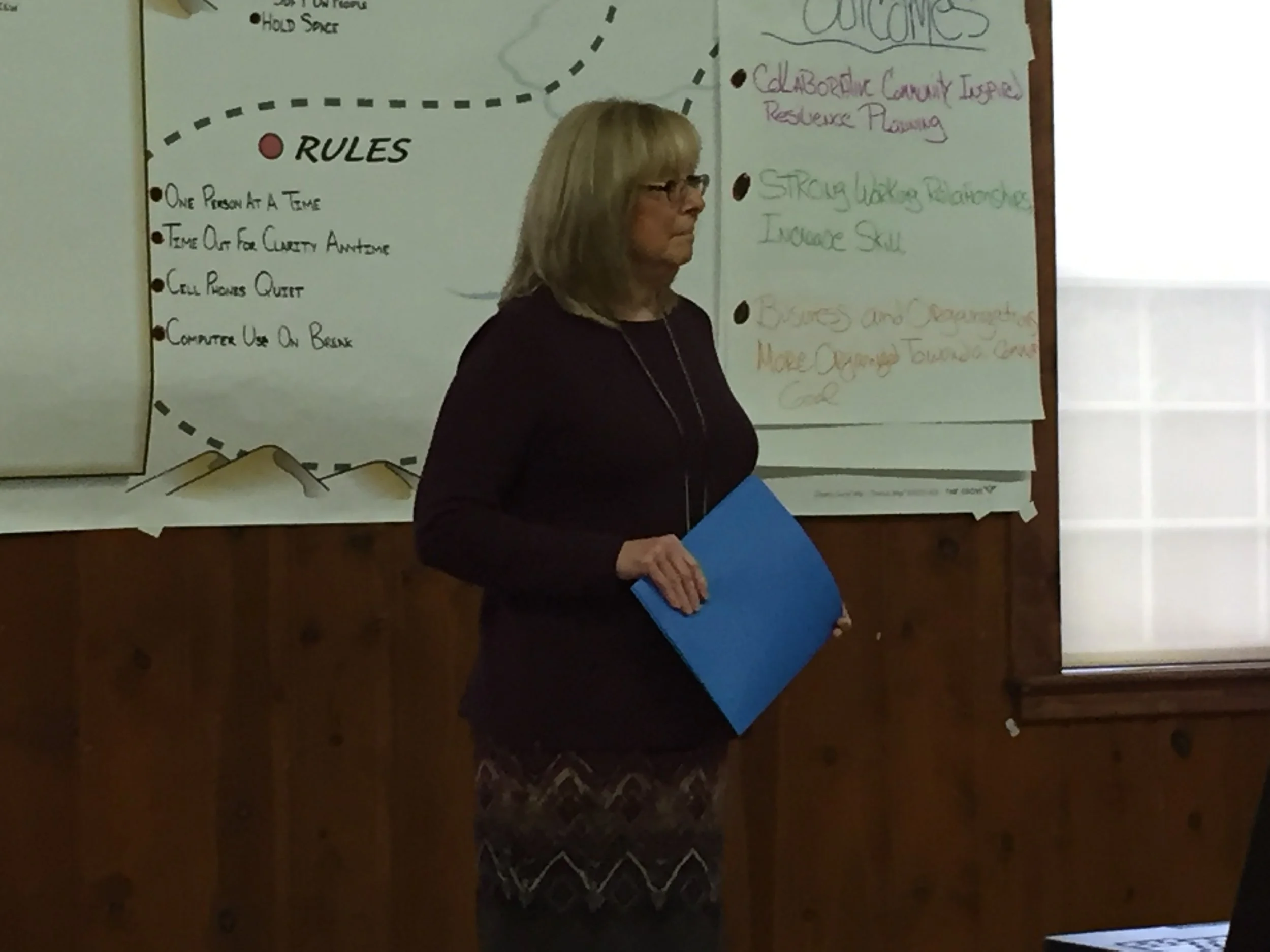

Developing a Rural Resilience Plan

After the fire, long-term recovery became the city's focal point of planning. The State of California Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program contacted the city about conducting “resilience planning," a planning process in which urban areas are now engaged. With the state's help and CDBG funding, Weed developed a Resiliency Plan to help create a clear vision for its future, leverage its resources, mitigate its risks, and help the city be prepared to survive in times of stress and disaster.

Most resilience planning efforts to date have focused on urban cities, metropolitan communities, and not on America’s rural communities. Resilience describes the capacity of communities to function so that the people living and working in a community– particularly the poor and vulnerable – survive and thrive no matter what stresses or shocks they encounter. Rural communities can face challenges in doing resiliency planning such as not having access to highly trained, local professionals and limited financial resources to implement the plan. Weed was an opportunity to adapt the urban resilience planning processes to a rural area. The efforts in Weed used these sources primarily: 100 Resilient Cities, ARUP’s Resilience City Framework, and JIBC’s Rural Resilience Disaster Planning.

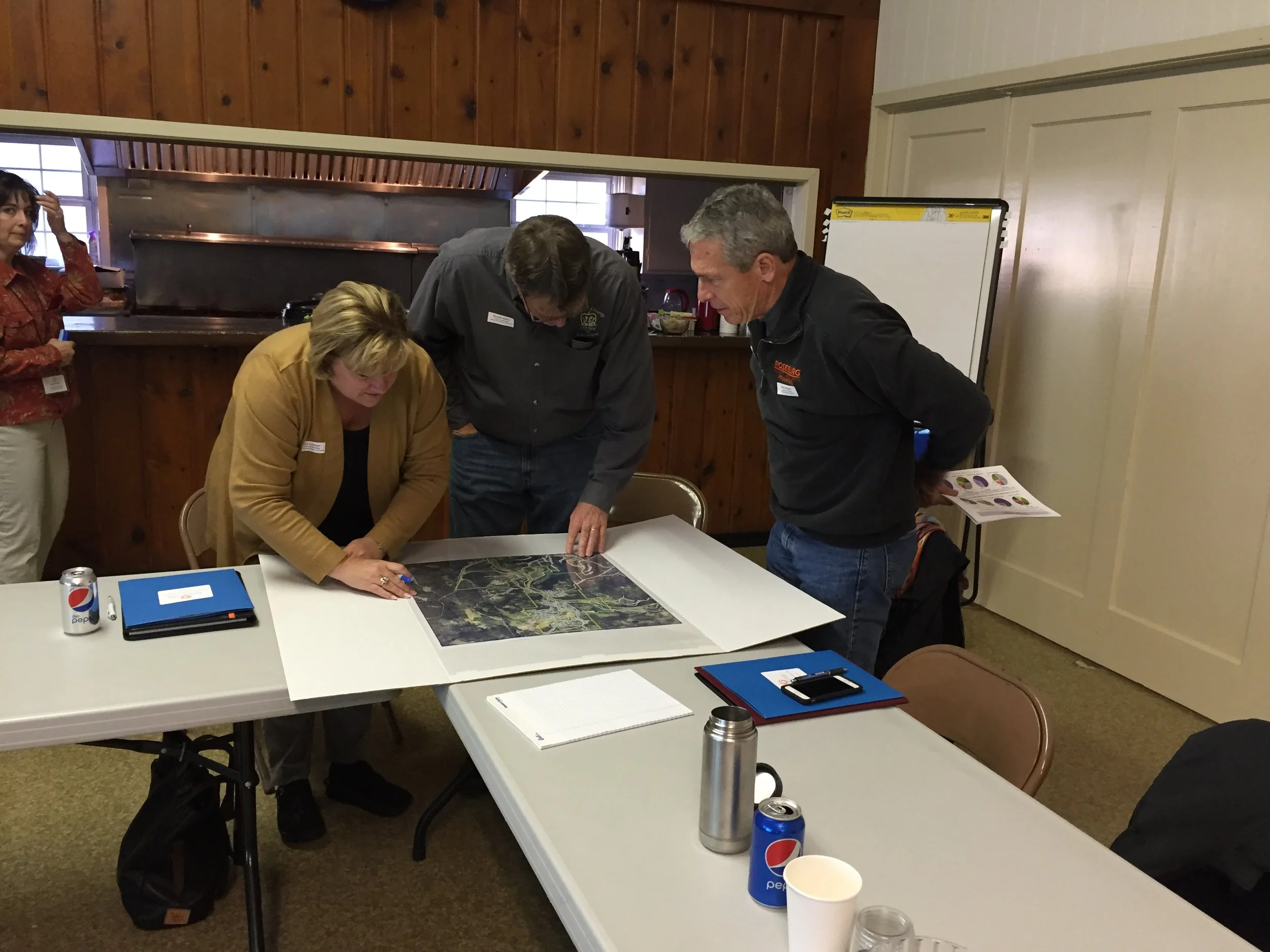

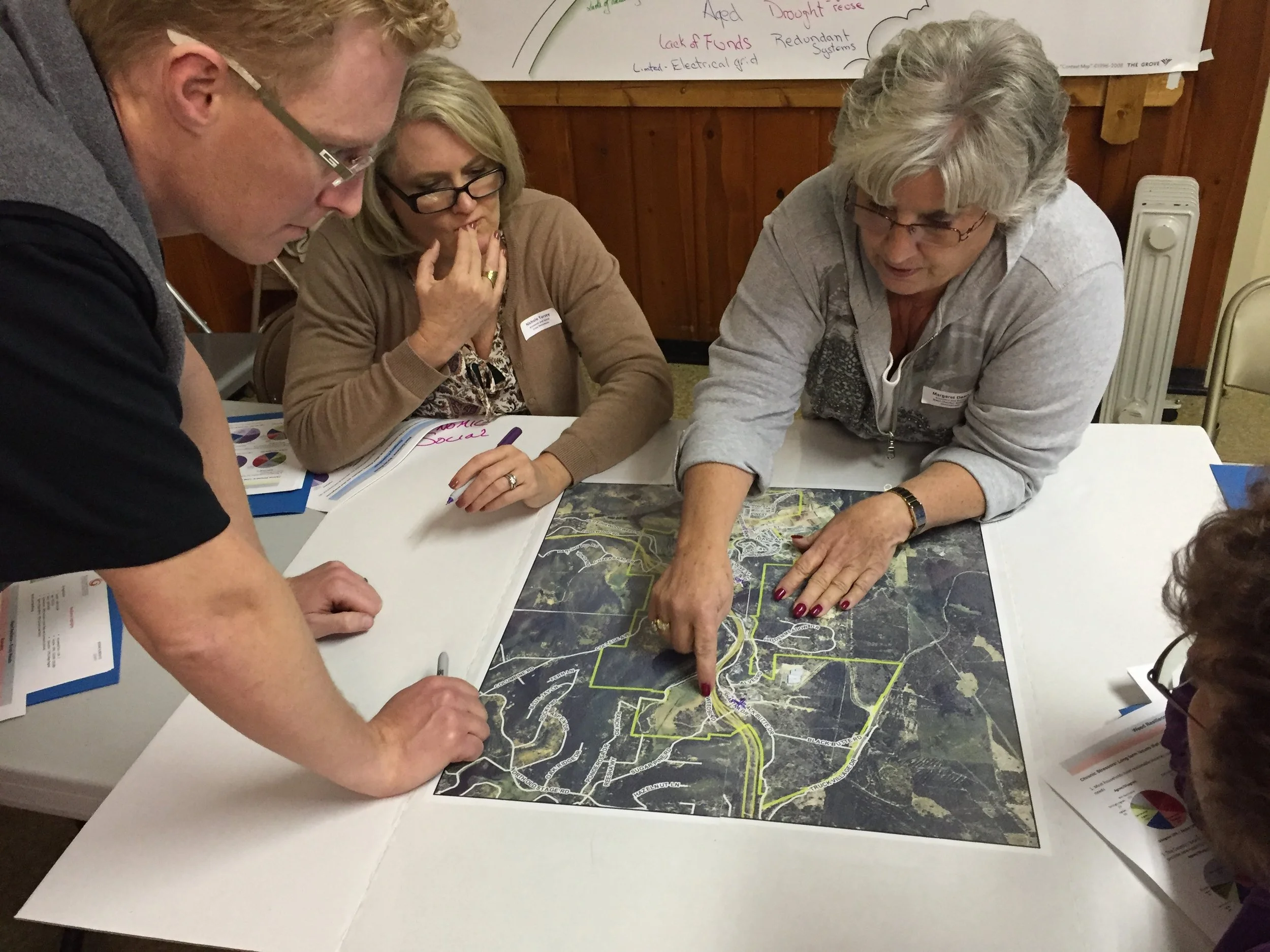

The goal of resilience planning is to assess the community’s qualities (assets) and vulnerabilities (impediments to resilience) and to make a roadmap to the future (resilience planning) based on the identified community needs, through a robust community planning process. For Weed, this meant gaining input from all facets of a community, from community members to leadership in Weed itself and areas under its sphere of influence. Input was gathered through a series of open public and leadership meetings, leadership interviews, an online survey, and executive team meeting conference calls. Further community participation was made possible by a Facebook page and a dedicated website where citizens could comment on the process.

Resilience Plan for Weed

The Resilience Plan for Weed does not include implementation, which requires creating an Implementation Committee whose members can work with the City of Weed to identify priorities, seek funding, and provide a focused, driving force behind implementation activity. The plan also recommended that the Weed City Council approve the plan and hire a half-time Community Development staff position whose primary responsibility is to administer the Resilience Plan and other community development projects.

Photo by Tom Brandeberry

Through the resiliency planning process, nine categories were identified. Within each category, attributes were prioritized and goals were assigned. Resources were identified for each person or entity assigned to enable working toward and achieving each goal. Please read the plan (PDF) to better understand each section.

- Leadership, Communication, and Planning: The capacity to provide needed services for a community, including a local government’s capacity and level of coordination when working closely with community members, leaders, and other local governments.

- Economic Sustainability: The existence of year-round businesses that continue to grow and diversify the local economy while providing employment for the livelihood support of citizens.

- Housing: Affordable and diversified housing stock, ensuring that all members of a community have a home in which to live, whether this is a house or some other kind of dwelling, lodging, or shelter.

- Infrastructure and Environmental Impact: The basic physical and organizational structures and facilities (e.g., roads, water supply, sewerage, telecommunication, and energy) needed to sustain a city and its sphere of concern; also how its natural environment shapes and impacts the area.

- Education: A community’s access to education and training, including elementary through college level curriculum.

- Health and Well-being: The strength and vitality of mind and body; the state of being comfortable, of having a happy and successful life.

- Social and Cultural: Acceptance, appreciation, belonging and companionship in a community, allowing social needs to be met by forging relationships with others.

- Non-Disaster Emergency Safety: The capacity to respond to everyday emergencies involving situations that pose an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment.

- Disaster Preparedness: A continuous cycle of planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluating, and taking corrective action in an effort to ensure effective coordination during a shock or disaster.

The Weed Resilience Plan was completed in April 2016. The plan was adopted by the council but much of the implementation has stalled due to funding limitations, and local city capacity to implement as they continue to manage basic recovery.

As for the community of Weed, rebuilding efforts are ongoing but reaching milestones three years after the fire. About 60 homes had been rebuilt by May 2017, with the hope of having three-quarters of the lost homes being rebuilt in 2019. (According to estimates by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protect about 157 single-family residences were destroyed in the fire.) (2) The Weed Long Term Recovery Group is winding down its case management, holding its last public meeting, and working on its final evaluation and summary report. The community center, destroyed along with 150 homes, is finally being rebuilt with the completion date set for the summer of 2019. The community came together with many donations and the city insurance money to pay for the $4.2 million center. A rebuilt Holy Family Catholic Church opened in May 2017 and the new Grace Presbyterian Church opened in September 2017.3

Importance of Rural Resilience Process

Rural America is important to all Americans because it is a primary source for inexpensive and safe food, affordable energy, clean drinking water and accessible outdoor recreation. 14% of Americans Rural America live and take care of three questers of America’s land mass. Rural communities ensure urban communities are feed, watersheds are maintained for clean drinking water, and there are places to go for outdoor recreation.

Rural communities must be livable communities. And a rural community resilience planning process not only addresses the safety of the community, long term, but it also tackles the stresses within a community that can make a rural community less livable. From addresses food insecurity (yes, rural communities can be food deserts), to high unemployment to a lack of heath care, higher education, youth services, and even child care, rural resilience planning attempts to build social capital by addressing the stresses of the particular community.

Rural Community Development Corporation of California

Rural Community Development Corporation of California (RCDCC), a nonprofit, was formed in 2017 to help fill the gap in capacity that rural communities, especially those considered disadvantaged, are beleaguered by. We at RCDCC believe with training, direction (planning) and support California’s rural communities can be more self-reliant, and create sustainable, livable communities that gain not lose populations. Visit https://rcdcc.org and see RCDCC rural resilience planning process here: https://rcdcc.org/the-process/

Tom Brandeberry started this process with Weed when he was the State Section Chief for the CDBG program, which funded the city’s resilience process. After retiring, he formed the nonprofit Rural Community Development Corporation of California (RCDCC) in 2017 to fill a gap in the needs of California’s disadvantaged rural communities. His experience comes from working at the Department of Housing and Community Development for over ten years, with seven of those years as a Section Chief for several federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD), programs (HOME, CDBG, and DRI).

Endnotes

- Resilience-Weed final plan: https://rcdcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/City-of-Weed-Resilience-Plan_Final.pdf

- Shasta Regional Community Foundation. Boles Fire Long Term Recovery Report http://www.shastarcf.org/stories/boles-fire-long-term-recovery#.WkVrSGhKuHs

- Record Searchlight “Symbols of recovery rise in Weed in fire’s aftermath,” May 28, 2017, http://www.redding.com/story/news/local/2017/05/26/symbols-recovery-rise-weed-fires-aftermath/101813192/

- Record Searchlight “Donation will help Weed Rebuild its community center,” October 12, 2017. http://www.redding.com/story/news/2017/10/12/donation-help-weed-rebuild-its-community-center/758308001/

Published July 2018