Lidar – An All-Purpose Tool for Assessing Flood, Landslide, and Fire Hazards

How a USGS 3DEP grant was used to obtain lidar for 2,662 square miles in the Clearwater River Basin, ID

by Alison Tompkins, Nez Perce County, Idaho

It began with a scenario all too common in rural Nez Perce County’s Planning and Building Department – the author (a county planner and floodplain coordinator) reviewing a building permit application for property in the floodplain. The FEMA Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) shows an approximate A Zone (a.k.a. 100-year floodplain) across a portion of the property, so the homeowner will be required to meet all floodplain development standards. The FIRM was published in 1983 after a 1970’s flood study. This may not sound so bad, except that in February of 1996 Idaho’s panhandle experienced massive flooding when sudden warm temperatures combined with four days of rain on winter snowpack. The massive 1996 event was declared a federal major disaster by then-President Bill Clinton. (Idaho Office of Emergency Management, 2016) It washed away barns and homes and relocated entire stream channels. Needless to say, vast portions of the FIRM map are no longer accurate, and portions that may be accurate are made less useful by the implementation of GIS digital mapping and aerial imagery that is light-years more advanced than the gray-scale paper flood maps of 1983.

Figure 1 – Example of Nez Perce County's 1983 FIRM map.

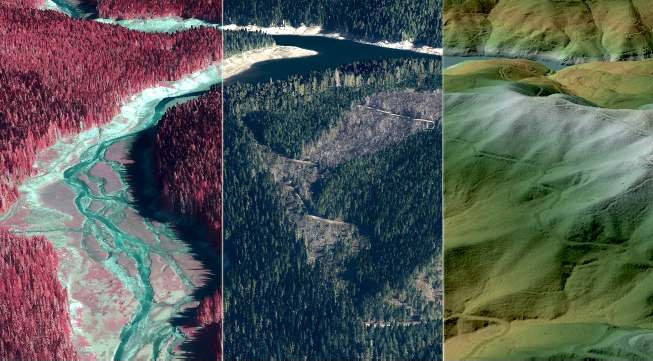

Despite the outdated nature of many FIRMs, communities across the nation are required to use them for floodplain management in accordance with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Although FEMA prioritizes communities in need of updated maps, communities are encouraged to obtain the data necessary to facilitate updated flood studies. What type of data is necessary? Highly detailed elevation data. But how does one obtain detailed elevation data for an entire county? Lidar – Light Detection and Ranging – is a remote sensing method that uses light to measure distances to the Earth. It is a highly regarded and desirable tool used to generate precise digital elevation data about the topography of the study area. This high resolution, three-dimensional elevation information can be used to update flood maps. It also has a multitude of uses across other disciplines (transportation, municipal/county planning, wildlife, and natural resources) for an infinite number of project planning, development, implementation, and management purposes. These include but are not limited to: project engineering for future highway projects, identifying land suitable for infrastructure and development, habitat and vegetation assessment, multi-hazard risk assessment, and more.

Figure 2 - A great example of lidar used for vegetation and bare earth imagery. Courtesy of Quantum Spatial.

Lidar sounds like the solution to so many problems, so what’s the catch? Cost. Despite its desirability, the expense of obtaining lidar data is often cost-prohibitive for a single entity. It can cost anywhere from $225-550/acre depending upon the quality level of data, type of terrain (flatter is cheaper), and size of the acquisition area (cost per acre decreases for larger areas). (Nez Perce County Planning and Building Department, 2016) Until recently, lidar data in Idaho was limited to small areas that were usually obtained as part of wildlife or watershed monitoring projects. In 2013, the Idaho Lidar Consortium was formed to provide a public repository for all Idaho lidar and a way to identify desired acquisition areas. This type of tool is very useful in identifying potential funding partners in your area.

How to Fund a Lidar Project

It takes time to form the connections needed to bring any project together, and a lidar project is no exception. The planner in the scenario above worked with the county GIS coordinator to explain to county commissioners that lidar data would benefit the public in several ways:

Facilitate updates to FEMA flood maps – Development in the 100-year flood plain is costly and requires flood insurance, elevation certificates, and floodproofing of new construction. Property owners can realize insurance and development savings when flood maps are accurate and show that property is not in a mapped floodplain: $1200+/year for flood insurance, surveyor/engineer costs to complete an elevation certificate before and after construction, and engineering and material costs for floodproofing new construction.

Public safety awareness and development plans – Lidar can be used to develop landslide and fire hazard maps to inform the public and can guide management policies to improve safety and reduce hazards with new development.

Stormwater – The highly detailed elevation data can be used with GIS and other hydrology software to calculate area and volume of stormwater runoff, information that is useful for project development and infrastructure planning.

Accurate aerial imagery –lidar can be used to more accurately construct surface imagery.

Other factors such as increased development costs can contribute to the public support of a lidar project. For example, surveyors hired to complete elevation certificates encounter problems when benchmarks like nails in power poles and trees no longer exist – power poles have been replaced and trees have been removed since 1983. This can require the surveyor to go miles to find another benchmark, adding to the survey cost. The property owner pays the price because the elevation certificate is required in order to obtain floodplain and building permits.

Fires, floods, and landslides increase public awareness of natural disasters. These hazards fuel multi-jurisdictional agency support for lidar which can be used to repair and/or mitigate damage caused by natural disasters. This happened in Idaho in 2015 when some of the worst fires in almost 100 years struck the state. 68,000 acres burned in the Clearwater Complex Fires, destroying 48 homes and over 70 outbuildings near Kamiah in the Clearwater River Basin. (Idaho Department of Lands, 2015)

Figure 3 - Clearwater Complex fire, 2015. Photo credit: Idaho County Free Press

This resulted in a heightened public awareness of fire hazards, followed by landslide hazards in the following years when burned areas experienced numerous landslides. State highways in steep river corridors of the Clearwater River watershed are high-risk landslide areas. The reality of landslide risks was demonstrated by a massive slide on Idaho State Highway 14 near Elk City in February of 2016, when 14 tons of debris slid across the highway, blocking access to the remote town. (KTVB.com, 2016) State agencies like the Idaho Transportation Department can use lidar for project planning, budgeting, and construction decisions to mitigate landslide hazards. Lidar can also be used by planners and emergency managers to identify areas of high landslide risk and guide development accordingly. Forest managers such as the Idaho Department of Lands use lidar to model fuel loading and fire behavior, analyze and calculate vegetative cover, and plan timber harvest to reduce the risk of devastating fires.

Figure 4 - Idaho State Highway 14 landslide. Photo credit: Idaho County Free Press

The 3 C’s: Communication, Coordination, & Cooperation

As a result of good communication with county commissioners about these issues and opportunities, in 2013 Nez Perce County (NPC) approved a budget which included $40,000 to match potential grants to fund a lidar acquisition. The money was not spent and was included in the budget the following two years with an additional $40,000 each year. During this time, the county planner, Alison Tompkins, communicated with various agencies about the possibility of a lidar project in Nez Perce County. Attending annual conferences for the Northwest Regional Floodplain Management Association (NoRFMA), floodplain administrator workshops, and asking how to proceed and who to talk to led to more connections. Groups like the Idaho Silver Jackets, Idaho Department of Water Resources, and the Idaho Office of Emergency Management (IOEM) can offer resources and valuable information for your project and get the word out to help build needed momentum to move a lidar project forward. [R5] Silver Jackets teams exist in states across the US, as do water resources and emergency management offices, though names vary slightly by state. It is important to know your state water and emergency management staff – a quick Google search will usually reveal the department titles used in your state.

For Nez Perce County, the tipping point occurred in 2015. Tompkins and the GIS Coordinator, Bill Reynolds, were communicating with the Nez Perce Tribe (NPT) GIS Coordinator, Laurie Ames, and had identified the desired acquisition area on the Idaho Lidar Consortium’s website. Tompkins was also communicating with IOEM about a potential FEMA RiskMap project within the Clearwater Basin. The fact that NPC had already budgeted money for lidar was looked upon favorably, though it was still not nearly enough to obtain lidar for all of Nez Perce County.

In the Fall of 2015, Nancy Glenn – Boise State professor of geosciences – submitted a grant application on behalf of Nez Perce County, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the Idaho Office of Emergency Management, for the U.S. Geological Survey 3D Elevation Program (3DEP). Together these participants committed to $226,000 in contributions, should the award be granted. In January of 2016, USGS 3DEP awarded $244,000 to the group, for Idaho’s first USGS 3DEP grant project, “Multi-hazard Risk Assessment and Ecosystem Restoration in Idaho”. The project included priority areas identified by NPC, the NPT, and IOEM – a total of 2355 square miles for Quality Level 2 (QL2) data[1].

After a series of conference calls coordinated by Glenn, Tompkins volunteered to coordinate efforts between all agencies interested in participating and/or contributing to the project. Countless contacts were made via phone, email, and personal meetings, in an effort to reach out to any and all agencies interested in participating. The broad applications of lidar data are a useful advantage when identifying partners for cost-sharing. Agencies quickly realized the benefits of participating – the cost per square acre of lidar decreased as the size of the acquisition area increased due to the reduced cost for aerial survey equipment already deployed. The project grew across states lines to include cities and counties in Washington, while the additional partnerships allowed the group to upgrade to QL1 data in select areas.

The USGS required a contract with a single entity at the state/local level, and Tompkins facilitated that process on behalf of Nez Perce County. Nez Perce County became the “funnel” through which all state and local funding partners would go through. This required Tompkins to track all professional and financial contacts with every agency, and coordinate contributions and invoicing while accommodating different fiscal calendars and budgets.

Meanwhile, Reynolds provided invaluable expertise as he collected GIS shapefiles of each participating agency’s priority areas. He compiled these layers to create a final map of the lidar acquisition area which incorporated the interests of numerous partners and stakeholders, including those not participating financially.

Reaping the Rewards

In June of 2016, the USGS 3DEP finalized the Statement of Work and Joint Financial Agreement for a final lidar acquisition area of 2,662 square miles for QL1 and QL2 data. The total project area encompassed seven counties in Idaho and Washington, with total contributions of over $930,000 from more than a dozen partners! Lidar flights were conducted in the Fall of 2016 during leaf-off conditions and before snowfall, and data was delivered in December 2017. It was the result of years of dedication to obtaining lidar for multiple and varied uses by local, state, federal, and tribal entities. The data is hosted by USGS and the Idaho Lidar Consortium and available to the public, free of charge, with virtually unlimited possibilities for how to apply it. Many of the participating agencies already have specific plans for use, and they are as varied as the agencies themselves. (See bulleted list)

The information gained from the Clearwater Lidar Project has both short-term and long-term benefits across a broad spectrum of disciplines, and encompasses project planning, development, implementation, management, and education outreach. It is truly a phenomenal example of how multiple agencies at local, state, and federal levels can cross disciplines and pool resources for a common goal.

Construction engineering

Transportation planning, design, and budgeting

Utility management

Mapping impervious surfaces

Drainage way management

Landfill capacity and cell design

Increase accuracy of aerial imagery and cadastral mapping projects

Wildlife habitat monitoring

Stormwater, erosion, and sediment control planning and design

Analysis of vegetative cover and timber stand metrics

Timber harvest planning

Assess and manage risks such as flood, fire, and landslide

Figure 5 - Map of the Clearwater Basin USGS 3DEP project area. Map by NPC GIS Coordinator.

Clearwater Lidar Project Participants

Asotin County, WA

Asotin Public Utility District

Asotin Metropolitan Planning Organization

City of Lewiston, ID

Idaho Department of Lands

Idaho Transportation Department

Lewiston Metropolitan Planning Organization

Nez Perce County

Nez Perce Tribe

Port of Lewiston

FEMA Headquarters

FEMA Region X

Natural Resources Conservation Service –National Geospatial Center of Excellence

United States Geological Survey 3D Elevation Program

United States Forest Service

Suggested sources for help on the topic:

Idaho Lidar Consortium https://www.idaholidar.org/

USGS 3DEP Grant https://nationalmap.gov/3DEP/

Idaho Silver Jackets https://silverjackets.nfrmp.us/

FEMA RiskMap https://www.fema.gov/risk-mapping-assessment-and-planning-risk-map

Alison Tompkins is the planner for rural Nez Perce County, Idaho. Her diverse background includes watershed restoration and monitoring for the Nez Perce Tribe and private

practice in landscape architecture. She graduated with a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture

degree from the University of Idaho in 2004. She is currently working on her Master of

Landscape Architecture degree from the University of Idaho, focusing on stormwater and

wastewater management through landscape design.

October 2018