Ranching with Fire and Rangeland Fire Protection Associations: Livelihoods, resiliency, and adaptive capacity of rural Idaho

by Kyle McCormick, MCRP, Boise, Idaho and Dr. Thomas Wuerzer, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Introduction

A majority of communities in Idaho are rural in character, and their ability to plan with fire is limited. The Rangeland Fire Protection Associations (RFPA) program, adopted by the Idaho Department of Lands within Idaho, is an effort to create better regional cohesion and allow ranchers to respond to fires on their land or their neighbors’ lands.

Within the United States, Oregon is the only other state to employ RFPAs. The State of Oregon created legislation for RFPAs in 1963, and its first RFPA was formed in 1964. Currently, there are twenty RFPAs in the State of Oregon and eight in Idaho. The voluntary program trains ranchers to be first responders to wildfires and offers an opportunity for collaboration between the ranching community and government agencies.

The program is aimed at providing fire protection to the 2.2 million acres of private rangeland in Idaho with no formalized fire protection, sometimes referred to as “no man’s land,”1 with the premise of “neighbors helping neighbors.”2 In doing so, RFPAs get assistance in the form of firefighting equipment and training to help with fire management activities such as prescribed burns. RFPA’s began in Idaho through a series of conversations between local ranchers, county commissioners, and state/federal employees. In 2013, these conversations led to the State of Idaho3 adding section 38-104B to the State Code and giving rangeland fire protection associations their legal foundation.

Rangeland Fire Protection Associations not only demonstrate great potential in rangeland fire protection but also capture the meaning of ‘social capital’ and ‘community adaptive capacity’ as resources and planning capacity. In addition, the creation and active participation of RFPAs will potentially increase the overall planning capacity in rural areas that often lack resources. We demonstrate this influence on planning capacity in rural regions at hand with Idaho’s first RFPA, located in Mountain Home, Idaho.

FIGURE 1 CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Reasoning for RFPAs and Planning with Fire

Planning literature is mostly focused on the wildland urban interface (WUI) in the proximity of urban areas. Little attention has been paid by planners to the isolated (rural) context of the WUI and its communities’ rural/ agricultural/ ranching landscapes, and their capability of planning with fire. Current research on planning and wildfire has five distinct themes:

Preventative Actions

Awareness and Risk Perceptions

Collaboration and Trust

Social Capital and Community Adaptive Capacity

Planning Capacity

Based on our research, we developed a conceptual model that explains how the Mountain Home RFPA is likely to increase planning capacity and fire preparedness and could be a blueprint for other ranching and fire-threatened communities. The Mountain Home ranching community is a resource dependent community in the classic sense. It is characterized by its dependence and attachment to its surroundings, knowledge of the land, and past experiences with fire.

Within rural communities, residents understand wildfires and are able to mitigate their risk. Some communities dislike government regulation and desire local independence. At the end, trust, communication, and collaboration play significant roles in getting wildfire mitigation projects completed.4 Social capital, “the ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of membership in social structures,”5 is an important factor. Wildfire protection efforts that build trust and do work collaboratively result in greater participation between community and agencies.6,7 Rural areas are leveraging coordination across organizations and, therefore, bringing additional stakeholders to the table for better planning and more resiliency.

In sum, by creating and increasing planning capacity a region creates and furthers the ability of local, state and federal agencies to comprehensively plan for the future, keeping fire in mind.

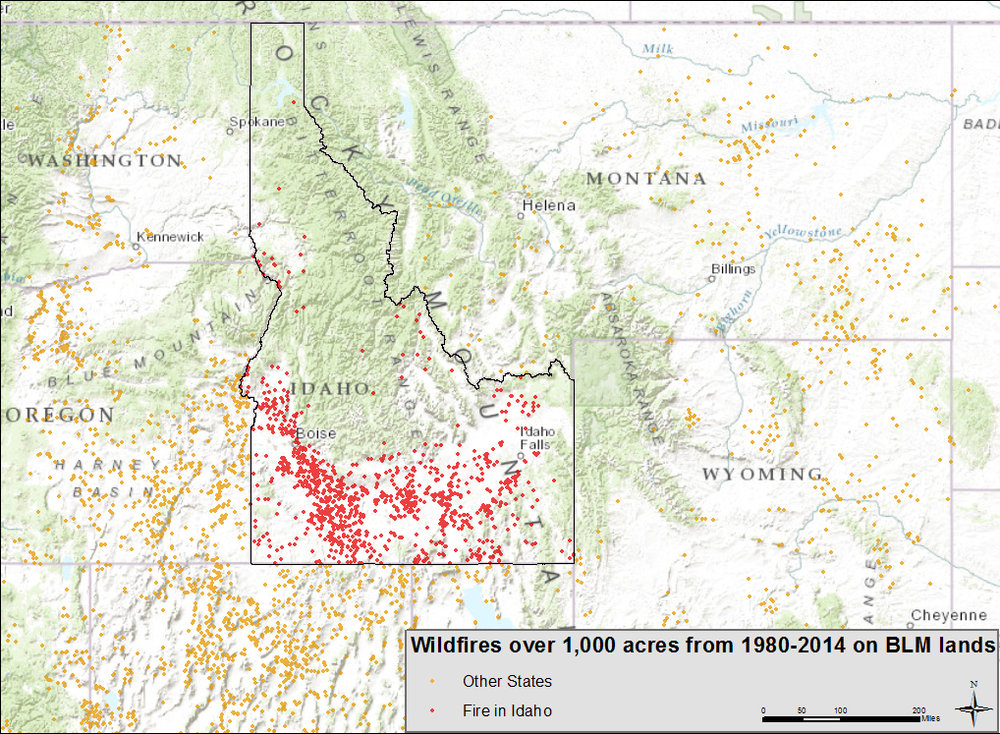

FIGURE 2 BLM “Originated” Wildfires 1980-2013

Rangeland Fire Protection Associations in Idaho and the Mountain Home RFPA

Wildfires have many different faces - the spectacular forest fires and the equally devastating, less media-covered, rangeland fires. The vulnerability of rural communities creates a need for planners to understand fire and “planning with fire.” An increase in rangeland fire activities also increases the potential for post-event impacts: greatly reduced availability of summer ranges, restoration efforts, and lost revenues create tensions mainly between federal agencies and ranchers.

Better planning with fire within rural ranching communities is contingent on regional planning efforts to coordinate and collaborate on efforts for pre-fire mitigation activities, timely response during the event, and post-fire restoration actions. When community members are engaged in processes of communicating and helping neighbors with reducing the risk, it leads to greater participation in wildfire protection. Rural communities that capitalize on this ‘social capital’ help planners in planning with fire.

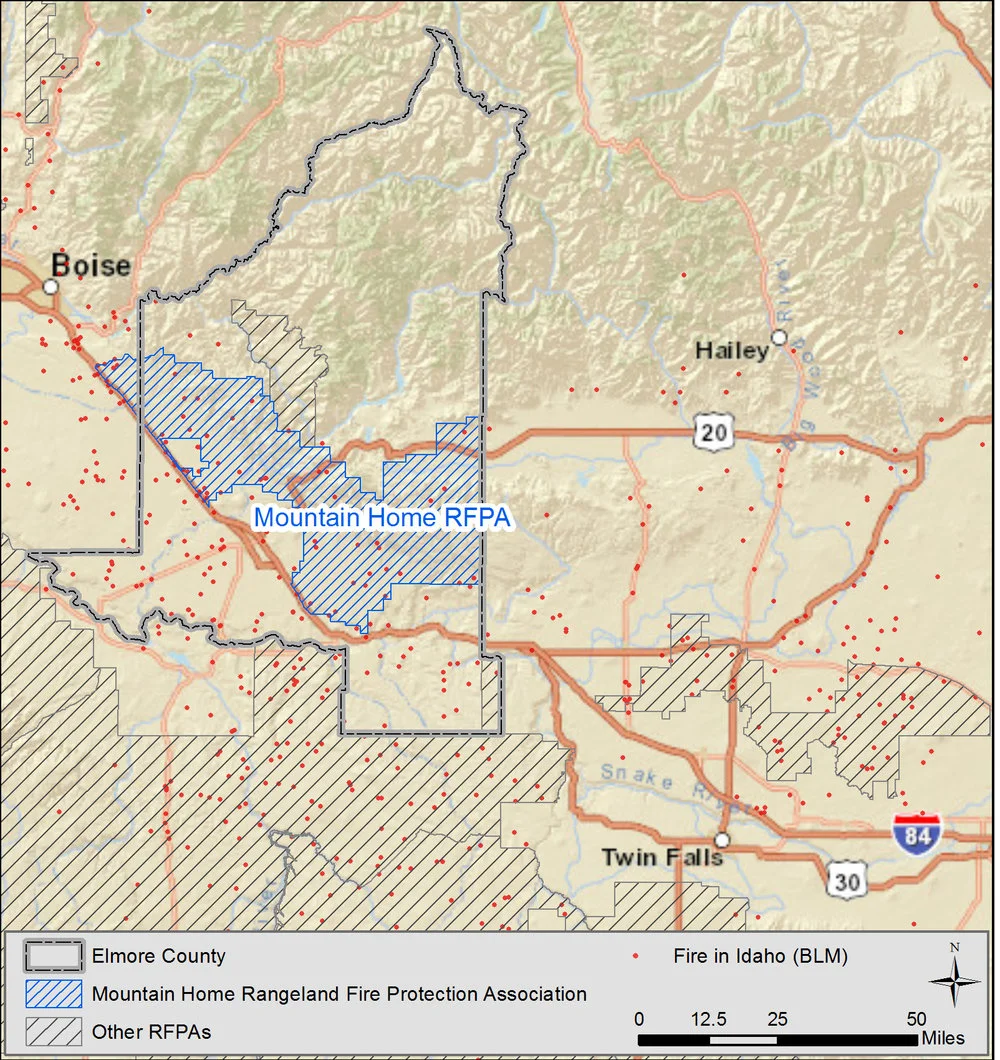

In order to establish an RFPA, ranchers have to form a formal group, obtain nonprofit status, and purchase liability insurance. Funding is then provided through grants, as well as governor’s and legislative appropriated funds. RFPAs are also funded through member fees and is structured with a board of directors consisting of RFPA members. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) then provides 40 hours of firefighting training to members. In forming an RFPA, local and regional capacities are likely to increase and foster; however, RFPA boundaries do not necessarily follow county or other administrative boundaries. Fires impact lands regardless of land ownership but is recorded/ ‘owned’ by its origin location. For example, a wildfire ignited by lightning strike on BLM lands is considered as a BLM fire. Figures 2 and 3 show the needs of increased collaboration in southwest and south Idaho at hand with just BLM-associated fires.

The Mountain Home RFPA consists of 30 local community members, encompasses approximately 540,000 acres of land, and is largely embedded in Elmore County (see Figure 3). Approximately 68 percent of the county is federal land, falling under the jurisdiction of the BLM, Forest Service, and Department of Defense (Mountain Home Air Force Base) while 22 percent is designated as farmlands. The majority of the county is sparsely populated and mainly rural.

FIGURE 3 Boundaries of Mountain Home RFPA

Findings

During the spring of 2015, semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders who were part of the process of creating fire-adapted communities, and in particular, those who were involved in the creation of the Mountain Home RFPA. Participants were from state and federal agencies (Idaho Department of Lands, Idaho Bureau of Homeland Security, Bureau of Land Management, local planners/employees, or rural fire districts) and are directly involved with RFPAs or were members of the Mountain Home RFPA. Using our conceptual model, the following are some findings, which can be used as lessons learned.

Preventative Actions

Members of the Mountain Home RFPA discussed not only how they participated on an individual level, but also how they are part of a larger community that is concerned with preventative actions. Local, state, and federal employees mentioned program plans that are in place for the community in the event of a wildfire.

Most members of the Mountain Home RFPA consider grazing to be their main form of mitigation on their property. However, after a fire burns through an area, cattle are kept off grazing allotments through federal regulations. This can create additional future economic hardship for the ranchers. Due to grazing regulations, ranchers stated that they are unable to reduce their risk in the most efficient way. Based on the interviews, the role that ranchers want to play lays in creating a community that can adapt to the threat of fire with appropriately managed grazing.

Awareness and Risk Perceptions

Participants were aware of the risk from wildfire, which can be attributed to the fact that this region is one of the most wildfire prone areas in the United States. Interviewed ranchers had a high perception of risk, stemming from their prior experiences and high investment in their property. Yet, there was no general agreement on whether the RFPA had created more awareness outside of its immediate ranching community. However, many participants noted that it is too soon to tell and that it is likely that these impacts will develop and increase over time.

Collaboration and Trust

We found that the RFPA’s intent to create more direct collaboration between ranchers and the BLM was successful. Many respondents noted that, prior to the RFPA’s creation, many public meetings regarding fire resulted in increased tension. However, the RFPA has successfully created a platform for partnership and trust on which regional adaptive capacity builds.

One reason is that the required 40 hours of training cultivates a network of communication. During this process, both parties become acquainted with the other’s point of view. Ranchers are more likely to understand why the BLM fights fire the way that they do, and the BLM became more aware of the issues happening within the ranching community.

Social Capital and Community Adaptive Capacity

The RFPA program is premised on neighbors helping neighbors while different perspectives touch on aspects of social capital and community adaptive capacity. Social capital shapes the way a community prepares for wildfire. Community cohesiveness, a result of social capital, helps prepare the entire area for wildfire by opening a line of communication among neighbors. Delineating official RFPA boundaries enables jurisdiction of where the RFPA is providing wildfire protection as well as increases the communities’ ability to prepare for wildfires in such area. Ranchers’ ability to come together and approach the IDL with their concerns is a display of community adaptive capacity.

Planning Capacity

The RFPA is a legally recognized entity that represents a geographical area that was previously lacking, mostly, in representation. Through the RFPA, the ranching community is able to participate in the planning process in a more meaningful way than before. Mountain Home RFPA members noted this the most. The improved relationship with BLM allowed ranchers to work with BLM range and fire programs to find mutually acceptable management options.

From the federal standpoint, improved RFPA/community participation drastically improves management decisions. Discussing issues and differing viewpoints related to range and fire management in a less hostile way results in more desirable outcomes.

At the state level, the RFPA increases planning capacity by grants for mitigation and preparation for wildfires. The RFPA program increased the ability of the Idaho Department of Lands to provide wildfire-planning services for rural areas.

At the local level, the RFPA is increasing the planning capacity in new ways. Since the program is in a startup phase, participants noted ways in which it could influence future local planning efforts. Local planners felt that the most important aspect of the Mountain Home RFPA was their ability to provide information and knowledge on wildfire, community issues, and, in the long run, change the landscape of the planning and permitting processes.

Conclusions

Characteristics of concept that RFPAs entail, such as neighborliness, collaboration, and the community’s adaptive capacity are influencing the planning process through an increase in participation from local ranchers. Understanding the role that the ranchers want to play in this process is an important issue that local planning departments should address.

The RFPA program in Mountain Home is effectively enhancing the planning capacity at the federal and local level through work completed on the regional Paradigm Project, a plan to create a series of fuel breaks in Southwest Idaho. They are placed along roadways and places where it would be most strategic to fight fires. The BLM included the Mountain Home RFPA within this process, and their input can be seen as a direct impact on the planning process for mitigating the risk in the area. Ranchers have been considered natural stewards of the land, and their opinion is extremely valuable. Increased collaboration has decreased turmoil between the ranchers and federal agencies. This improved relationship is the first step in creating a fire-prepared community.

Based on the findings, creating a partnership through a RFPA is likely to increase the planning capacity within a rural area and make up for some of the shortfalls that rural planning departments face during the planning process. This means that, whenever an issue of wildfire planning emerges, the RFPA could give worthy advice. This will increase the planning capacity in rural regions. In addition, the RFPA is effective in increasing the fire awareness of the ranching community through serving as a forum to share ranchers’ experiences. Therefore, the ability to prepare, respond, and recover can be enhanced by the presence of an RFPA.

The Mountain Home RFPA is an example that was followed by other rural areas in Idaho that are experiencing the same problem. Among most participants, the creation of the Mountain Home RFPA has had a very positive impact on the community. Reducing the risk with collaboration and the resulting trust can help planners at the federal, state, and local levels become more aware of community concerns. The ranching community within the Mountain Home region shows how community adaptive capacity is influencing the resiliency of a rural region. In particular, the Mountain Home RFPA has shown what this unique array of partnerships and actions can do for a rural ranching community that is vulnerable to wildfires.

The findings also suggest that the level of participation among members of the Mountain Home RFPA has increased involvement in and efficiency of the planning process. The level of collaboration between federal agencies and the ranchers of the RFPA has increased dramatically in the eyes of interviewed stakeholders. This collaboration has helped the community protect their assets from wildfires by building more cohesive units and being more prepared for the threat of wildfires.

Kyle McCormick, MCRP, works as planner for Canyon County’s (Idaho) Development Services. He was part of the Wildfire Mitigation Team of the Southwest Idaho Resource Conservation and Development Council and City of Boise. Dr. Thomas Wuerzer is associate professor for Real Estate Development in the H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneurship at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. His applied research focuses on investigating complex spatial issues with geographic information systems (GIS).

References

Idaho Department of Lands. (2008) Managing Fire on Lands Protected by the State of Idaho. Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Lands. State of Idaho. Retrieved May 3rd, 2016 from: http://www.idl.idaho.gov/fire/Idaho_Fire_Handbook_v10-7.pdf

Idaho Department of Lands. (2015) Rangeland Fire Protection Association: Neighbors Helping Neighbors. State of Idaho ID. Retrieved May 3rd, 2016 from: http://www.blm.gov/style/medialib/blm/id/fire/RFPAs.Par.92717.File.dat/brochure-rfpa.pdf

Idaho, State of (2013). Section 38-104B. NONPROFIT RANGELAND FIRE PROTECTION ASSOCIATIONS. (Retrieved May 3, 2016 from https://www.legislature.idaho.gov/idstat/Title38/T38CH1SECT38-104B.htm

Martin, I. M., Martin, W. E., Raish, C., & Rocky Mountain Research Station (Fort Collins, Colo.). (2011). A Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Risk Perception and Treatment Options as Related to Wildfires in the USDA FS Region 3 National Forests. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Portes, A. (1998). Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1.)

Lachapelle, P. R., & McCool, S. F. (2012). The Role of Trust in Community Wildland Fire Protection Planning. Society & Natural Resources, 25, 4, 321-335.

Sturtevant. V., and Jakes. P. (2008) Collaborative Planning to Reduce Risk. In B. Kent and C. Raish (Eds.), Wildfire Risk: Human Perceptions and Management Implications (pp. 44-63). Washington DC: Resources for the Future.

Resources

Driscoll, A. (2007). Wildland Firefighting: Neighbors Helping Neighbors (Oregon., Department of Forestry.). Salem, Oregon: Oregon Dept. of Forestry. Spring Issue, 2016 Volume 86, No. 2

Scholz, H. (2015, October 06). Protecting Rural Lands. Retrieved April 30, 2016, from http://portlandtribune.com/ceo/162-news/275788-151198-protecting-rural-lands

Data for visualization: ESRI, IDL, BLM, and United State Geological Survey Fire Occurrence Data

Published in July/August Issue of The Western Planner