Taking the Pulse of Tribal Transportation

by Cole Grisham, AICP

Image 1: Badlands National Park, near the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

Introduction

With 574 federally recognized Tribes in the United States—each vastly differing in population, territory, and geographic location—understanding the transportation interests of Native American and Alaskan Native communities is a highly contextualized effort (BIA 2021). Indeed, there are few practice-oriented studies of the transportation interests of Tribal communities and those that exist are becoming dated. Two resources for practitioners, Tribal Transportation Programs and Transportation in Tribal Lands, are 14 and seven years old as of 2021, respectively. This year, however, the Transportation Research Board’s Standing Committee on Native American Transportation Issues gathered insights on the transportation issues and opportunities facing Tribal communities from Tribal transportation practitioners directly. The goal was to gather more of a snapshot of what Tribal transportation practitioners are interested in right now that can guide other research goals moving forward.

In this paper, I outline the approach and findings from a recent workshop on Tribal transportation issues. While not an exhaustive survey, the workshop did provide broad insight into the issues and opportunities Tribal transportation planners encounter currently and expect to encounter in the future. To start, I outline my approach to gather the information, including the medium and questions. Second, I illustrate the major findings and themes. Third, I provide a discussion of what these insights might mean for future studies and planning practice generally. Lastly, I close with a few reflections on the workshop, including the value of less formal and open source platforms for virtual public involvement and data collection.

Approach

The virtual workshop held in September 2021 used collaborative, web-based tools to generate discussion and brainstorm issues and opportunities between participants. The workshop included the members and “friends” of the AME30 committee as well as attendees of the National Transportation in Indian Country Conference (NTICC), which was held the same week. In this paper, I refer to participants and Tribal transportation practitioners generally, since the audience consisted of planners, engineers, and other related professions.

While a number of tools exist to facilitate this type of virtual group brainstorming, I used Google’s Jamboard application. For those that have never used Jamboard or similar tools, the basic purpose is to allow participants to add notes to a white board, organize thoughts, and edit ideas collectively in real time. Users create a series of boards that the group can navigate through together and add content to throughout a workshop.

My approach was to first prepare the slides we would use in advance including the broad questions for each board. In the meeting, I shared my screen and demonstrated how to use and navigate through the application for participants. I then added the collaboration web link into the meeting chat pod so that users could pull up the Jamboard pages on their own screen for collaboration. From there, I facilitated a discussion and brainstorming session on the following questions (one question per board):

What are your Tribal transportation issues and concerns?

What information do you wish you had to build on your Tribal transportation efforts?

How do you envision your transportation system in 5 years? 10 years? 20 years?

What criteria should AME30 use to develop and choose future research proposals?

AME30 purposely kept the number of questions to a minimum so as to focus more time on each one and allow for each to build on the last. For each question, participants added their notes and comments to the board, and, over time, other users began grouping content by broader themes. Where there was confusion about a note's content, I asked participants to talk through for further clarification, whereby they or others would add more notes for clarification.

The process lasted about 45 minutes, with closing discussion on how the feedback would be used to inform AME30 research focuses. We also chose to leave the Jamboard open for an additional 24 hours in case participants had other thoughts to add or would like others they know to participate. After closing the Jamboard, I further organized notes into the themes identified in the workshop and adjusted note colors for easier visual navigation.

Findings

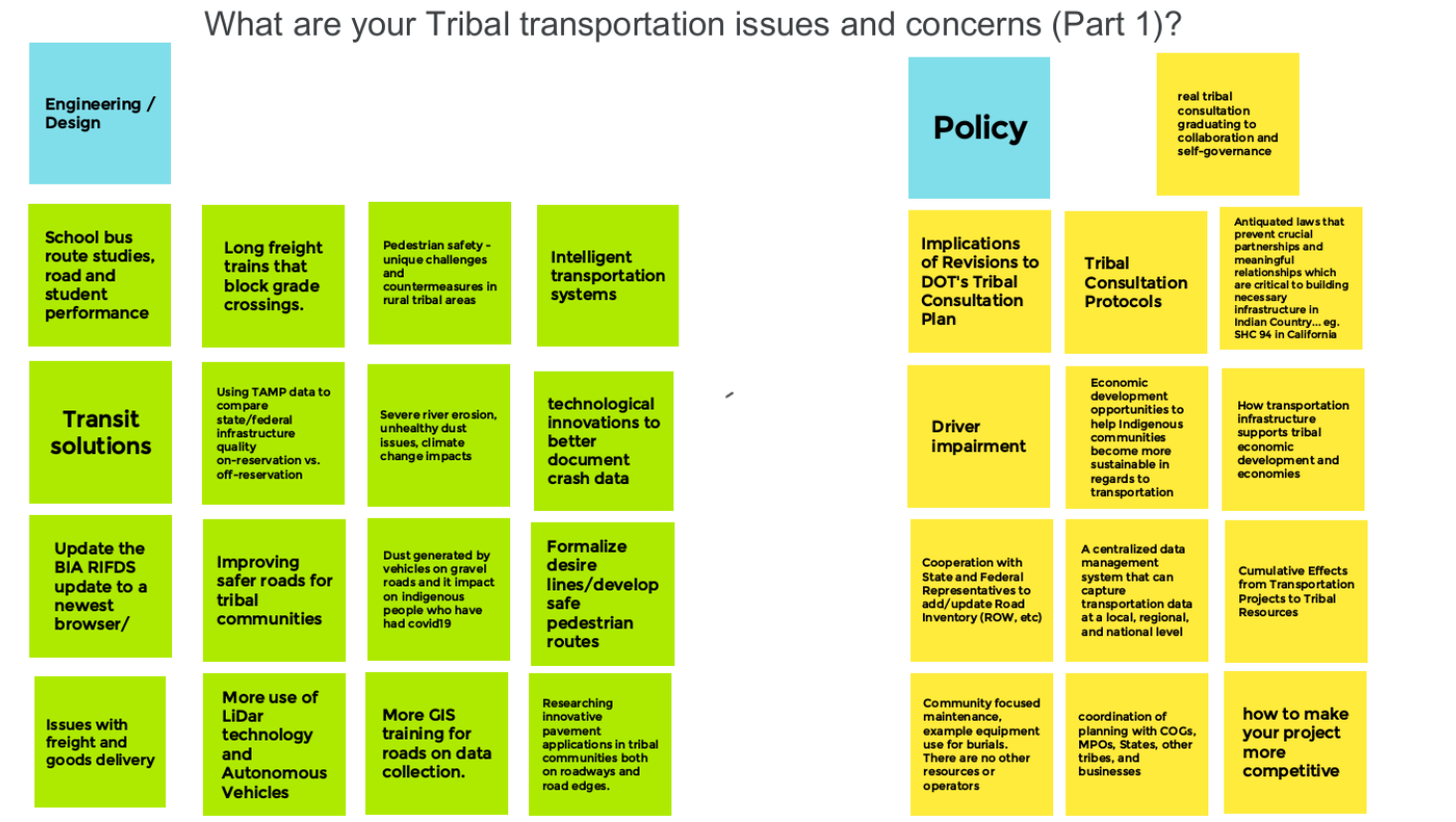

The information gathered during the workshop is shown in Figures 1-4 below. Figures 1a-1b are two parts of the same discussion, since this question raised quite a bit of feedback. For easier viewing, I separated out this content into two different boards.

Figure 1a. What are your Tribal transportation issues and concerns (Part 1)?

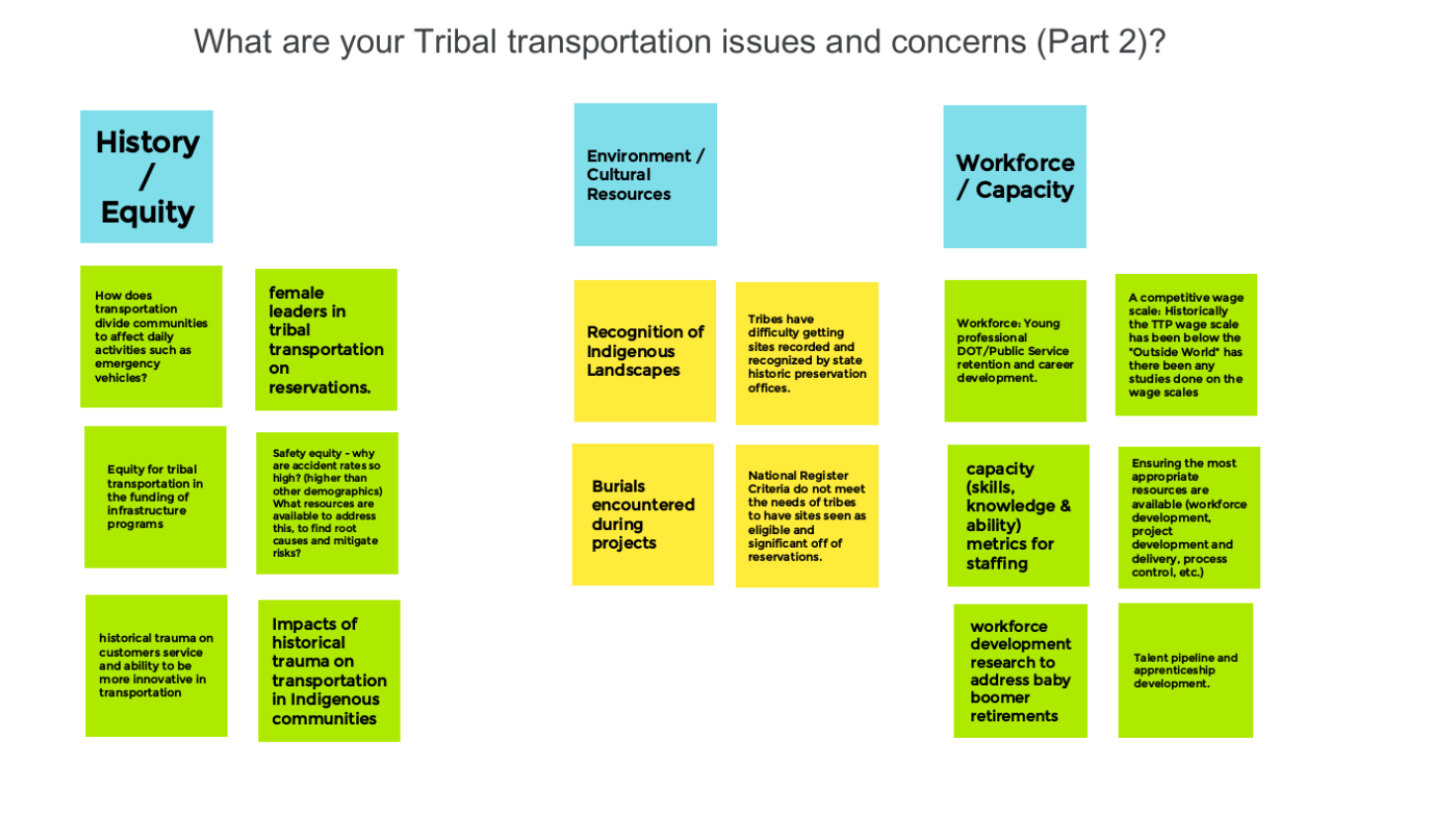

Figure 1b. What are your Tribal transportation issues and concerns (Part 2)?

The major themes for Tribal issues and concerns center on engineering and design, policy, history and equity, environment and cultural, and workforce and capacity issues. Many issues shown for Tribal communities are similar to those one would see in rural or small-town planning generally, such as freight trains blocking road crossings, dust pollution from gravel roads, and early career staff retention. Others are clearly unique to Tribes, such as government-to-government consultation, recognition of Tribal burial grounds, indigenous landscapes, and cultural resources.

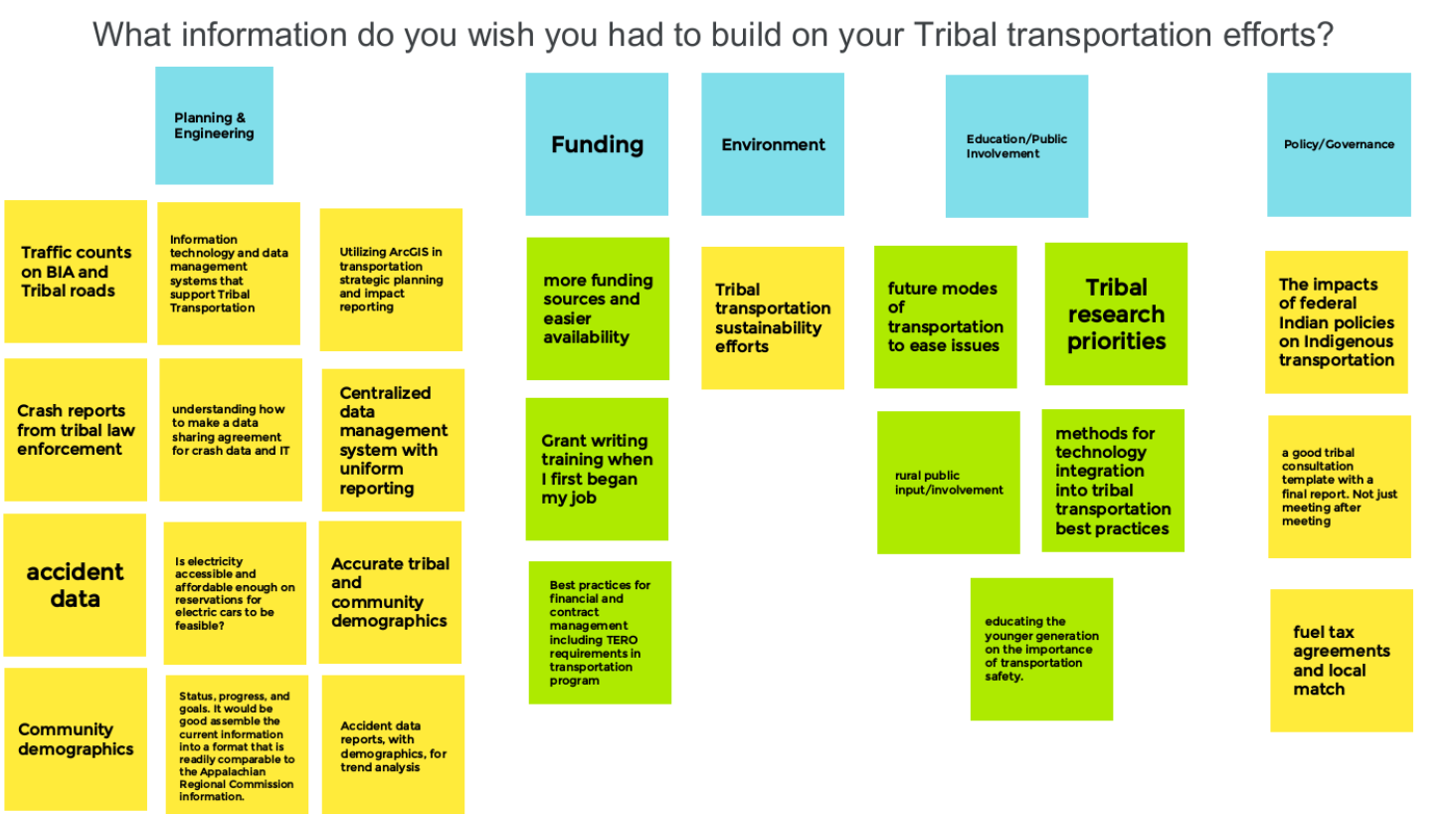

Figure 2. What information do you wish you had to build on your Tribal transportation efforts?

Information needed for Tribal transportation practitioners falls into five broad themes: planning and engineering, funding, environment, education and public involvement, and policy and governance. Other than two policy and governance notes, nearly all comments are common challenges and opportunities for all planners. Indeed, most of these reflect my own planning needs when I was with a state Department of Transportation as well as in my current position. The distinction we can see is the desire to see information applied to Tribal contexts, such as what sustainability planning looks like from a Tribal perspective or crash reporting from Tribal law enforcement.

Figure 3. How do you envision your transportation system in 5 years? 10 years? 20 years?

After discussing issues and information needs, we then moved to where Tribal transportation practitioners see their transportation system in near and long terms. We did not qualify this question as ‘how participants hope their transportation system will be,’ which is more common for visioning exercises. Instead, we left the question open to where participants actually envision their system going, for better or worse. The content in Figure 3 is broad, but what we see in terms of themes are the desire for more and better travel modes, improved safety, improved freight and commercial options, and more sustainable, effective, and adaptable Tribal transportation departments (i.e., greater project delivery options, more competitive at funding opportunities, and more skilled staff).

Figure 4. What criteria should AME30 use to develop and choose future research proposals?

The final discussion focused on the criteria through which Tribal transportation practitioners believe research should be selected. What we found was that some participants had ideas of specific research topics that should be pursued (left side of Figure 4) while others were more interested in the selection criteria aspect. I focus more on the latter. Criteria of safety, equity, quality of life, and leveraging partnerships fit well with non-Tribal planning processes and indeed can be found in just about any transportation plan outside of Tribal communities. The distinction we can see for Tribal communities is the respect to Tribal interests and application. For example, one note suggests contextualizing research proposals to specific reservations, since each reservation’s context is distinct from one another. Similarly, participants want to see research that incorporates Tribes into the research process and utilizes Tribal research institutions (“utilize our tribal colleges in education and training”).

Discussion

The approach above provides insight into the minds of Tribal transportation planners at one point in time. For our discussion, I focus on three initial observations while recognizing that further conclusions could also be drawn from these slides. I also caution against generalization of a single event to be fully reflective of an entire community—especially one as diverse as Tribal transportation practitioners.

1. Similarities with other Planning Contexts

We can clearly see that Tribal transportation practitioners have interests and issues in common with planning practice generally, especially in rural and small-town contexts. For example, safety and related data needs featured prominently throughout all discussions, but these are not at all uniquely Tribal issues. Safety is often one of the top policy priorities in a transportation plan in any community (if not the #1 priority) and would be expected in this discussion simply by virtue of being a transportation professional gathering. The same could be said for equity, which is growing in acceptance as a priority in the planning profession, or the desire for more diversity in modal options, which is certainly relevant to rural planning needs today.

2. Distinctiveness of Tribal Transportation Contexts

While there are overlapping concerns between Tribal and non-Tribal contexts, we can also see areas that are distinct to Tribal contexts. These are mainly expressed in the unique aspects of government-to-government relationships between Tribes and other governments. We can see an emphasis on improved consultation between federal, state, and local governments with Tribes as well as the desire to be more self-sufficient (i.e., infrastructure tax base, workforce retention, and flexible contracting options). There is also an emphasis on respect by non-Tribal groups for Tribal landscapes, cultural resources, and historical inequity and trauma. In other words, the notes and related conversation showed a consistent desire for respecting Tribal sovereignty and self-determination while recognizing the complex intergovernmental network within which planning operates.

3. Making Planning Applicable

The last major observation is ensuring planning practices are applicable to Tribal communities. In other words, many of the planning tools and practices available to the profession are targeted to broad audiences at local, state, and federal governments as well as private and non-profit groups. The tools are not necessarily good or bad, but instead often are not tailored to Tribal contexts. For example, Figure 2 shows the information interests for Tribal transportation practitioners, noting the need for crash reporting data between Tribal law enforcement and planners, how enough electricity can be provided for electric vehicle infrastructure on reservations, and what public involvement looks like in Tribal communities. Focusing on the crash data issue, many state and local governments use the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) to consistently analyze transportation safety issues between jurisdictions. They can then use the consistent safety data as a basis to compete for federal transportation safety funding. For Tribes, this system often undercounts accidents (especially non-fatal accidents) since many go unreported to Tribal law enforcement or are not relayed from law enforcement to the FARS system (Grisham 2021). The result is a systemic disadvantage to Tribal communities in analyzing and addressing transportation safety, since this common planning tool does not address Tribal data well.

Going forward, projects like FHWA Federal Lands Highway’s Transportation Planning in Tribal Communities can hopefully close the gap between what tools are available and how to make them most useful to Tribal transportation practitioners. Staying with the safety and crash data, this has looked like providing common tools for Tribal planners to collect anecdotal crash information, convert it to quantitative and spatial data, and supplement wider datasets like FARS.

Conclusion

What do we do with this information? Most directly, AME30 will use this as a starting point to focus their strategic planning and research goals. But there is more to gain here than just that. A close reader of Figures 1-4 above will find a variety of broad or cross-cutting themes I have not addressed as well as specific topics that may be more important than what I draw the reader’s attention to. That is great—I hope readers will find more and different insights in these Figures than what I initially found. What I have shown is not by any means an exhaustive, polished or prioritized list of the issues and opportunities Tribal transportation practitioners encounter. Instead, this exercise and the resulting data show two points that might be valuable to other planners.

First, that there are a variety of less formal ways to collect information from communities that are still relevant to planning processes. Using online collaborative tools like Jamboard in settings like the AME30 and NTICC virtual meetings provides a good opportunity to take the pulse of the community we as planners serve. It can help guide future planning decisions, validate or overturn assumptions, and above all, generate helpful group discussion about what is most and least important to a community at a given point in time.

Second, tools like the approach I used cannot be the only tool in our toolbox. The approach I described works for small, informal gatherings where participants are self-selecting. In other words, there is little outreach on the part of the planner (me) to bring participants into the conversation. That means there are very likely large gaps in the perspectives, not just from other practitioners not present but also those impacted by transportation decisions generally in Tribal communities. This approach, therefore, is a valuable but narrow one. Instead, we must be cognizant of using the right tool, for the right purpose, in connection with the wider set of planning tools at our disposal.

Taking the pulse of the Tribal transportation community like we did was a great opportunity to collaborate with Tribal transportation practitioners. It allowed us to have a creative discussion about what is on the minds of our peers working directly on Tribal transportation issues and also for each of them to build on one another’s ideas in real time. For this event at least, we used the right tool for the right job.

About the Author

Cole Grisham, AICP is a Transportation Systems Planner for the Western Federal Lands Highway Division. He won the 2021 Stan Steadman Article of the Year Award for his previous article, Five Planning Ideas for the Oregon Coast Trail.

References (where not linked in text)

Bureau of Indian Affairs. 2021. Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved October 2021 from: https://www.bia.gov/frequently-asked-questions

Grisham, C. 2021. How to Better Leverage Tribal Transportation Safety Funding to Meet Long Range Transportation Needs [Presentation]. Presented at the 2021 Virtual Alaska Planning Conference. Slides available upon request from author.