Integrating Water and Land Use Planning in Colorado

By Andrew Spurgin, AICP

Across the West, communities are grappling with the challenges of growth, infrastructure and water supply. Drought in the Colorado River Basin (and elsewhere), uncertainties over climate change and land management policy further emphasizes the need to balance growth and resources.

Figure 1. Westminster Station

Westminster, Colorado is a growing city of over 113,000 in the Denver-Boulder corridor. Today the City boasts employers in technology, aerospace, energy and healthcare and a diverse housing portfolio. Westminster is currently in the midst of redevelopments that will see a new downtown emerge from the site of a defunct mall as well as a transit oriented development with rail access to downtown Denver.

Over the last 70 years, in an effort to stay ahead of always-present water concerns, the City has taken successive steps to continue to provide a reliable and safe water supply, manage growth, and adapt to changing needs. Through this, a culture of teamwork has thrived between the City’s Community Development and Public Works & Utilities staff.

Importance of Managing Growth

⦁ Water is limited. Colorado is water-short and has limited means to meet growing water demands. The Colorado Water Conservation Board, the State agency charged with establishing water policy, has identified a 2.5 to 7.5 million acre-foot by year 2050.

⦁ Land is limited. During the past several decades, annexation was a prime tool to manage growth and extension of public services; today many of these communities, like Westminster, that surround major cities across the West are “first-ring suburbs” with fixed boundaries and must exercise judicious planning for remaining development sites.

⦁ Balancing growth is crucial. Planners are mindful of growing too fast and consider impacts to utilities, transportation, and public services. This concern is extended to land use composition, such as providing a variety of housing types and future employment uses.

Figure 2. Westminster and Standley Lake

Background

Westminster incorporated in 1911 and remained a rural town until construction of the Denver-Boulder Turnpike began to change the City’s fortunes. Completed in 1952, the Turnpike bisected Westminster and facilitated access to Boulder and Denver with both housing and employment growth along the corridor.

Rapid growth during the 1950s strained Westminster's water supply. Although water rights purchases and construction of the City’s first water treatment plant in the 1950s served the City well, changing environmental factors in the early 1960s set off a twenty-year effort to secure a long-term supply. During the "Long Hot Summer of 1962", the City began using "safe, but stinky" water from the Kershaw Ditch in order to keep up with demand. On a hot afternoon in late summer, a group of women gathered for what is known as the "Mothers’ March on City Hall." Armed with signs and posters, the women paraded around City Hall for television cameras and newspaper reporters demanding safe water.

Figure 3. 1962 Mother's March on City Hall

A citizens committee demanded that Westminster discontinue using ditch water, stop issuing building permits, ban lawn sprinkling, and pursue water from Denver. Two voter referendums held to join Denver Water failed to pass. By maintaining its own water utility, Westminster retained greater control over its destiny. During this period of time, voters approved home-rule government, which set up the City’s current governance structure. In subsequent elections, voters approved major bond issues to pay for development of water resources and a new treatment plant finally gave the City a reliable water system designed to allow for growth.

Figure 4. Population Growth 1920-2018

Teamwork

In 1970 and 1971, the City’s land area enlarged from 4.5 square miles to 28 square miles and during the decade of the ‘70s, the population more than doubled from 19,512 to 50,211. Approval of new subdivisions got ahead of the water and wastewater infrastructure, in particular treatment plant capacity, and so by 1977, the Westminster City Council realized quality of life, particularly the capacity to provide municipal services, could be jeopardized if growth was not managed. A temporary building moratorium was enacted in 1977 to allow a “time-out” to plan. This created a dialogue between City staff in the Planning, Building and Water Resources divisions to identify a system of service allocation. More importantly, it fostered teamwork and brought the groups together for a common purpose.

To deal with this unprecedented growth, a yearly “Service Commitment” allocation system was established based on the City's ability to absorb new growth. The program included a "pay as you go" system of financing capital expansions to further emphasize conservation. Pacing growth allowed the utility system to separate from the City’s General Fund and become a self-supporting fund, which resulted in improved fiscal health for the City.

Despite good work, including the Service Commitment structure, which laid the foundation for planning and fiscal stabilization City staff realized by the early 1990s that merely pacing development with the existing tap fee structure was insufficient to pay for future infrastructure. The main reason for this was a lack of correlation between tap sizes and actual water use. The City needed both the ability to collect infrastructure-funding revenue and better water usage data to improve the methodology behind setting tap fees. What developed was a method combining tap size and estimated water resources.

This period of innovation fostered a close relationship between the City Planning, Building and Water Resources staff. Water resources staff developed a spreadsheet with formulas to calculate tap fees and tap sizes based on actual fixture counts. Once the Building Division saw how well this tool worked, they began to develop other spreadsheet calculators for both staff and customers. This helped save worktime for City staff and brought both groups together.

Figure 5. Tap Fee Worksheet

Collaboration

A significant drought that impacted the Colorado Front Range in 2002 once again created awareness of how water use affects the built environment. Poorly installed sprinkler systems and landscape materials showed more stress during the drought and undersized taps required more water than drought restrictions allowed due to inadequate water pressure. In response, two City staff - a landscape architecture and a trained planner, worked together with a water resource analyst and all three collaborated to prepare drought-tolerant landscape regulations. To ensure the program’s success, the Public Works & Utilities Department funded two positions in the Community Development Planning Division: a landscape architect charged with landscape design review and an inspector charged with irrigation and landscape installation review. These changes reduced staff workload and, more importantly, water use.

Figure 6. Drought Tolerant Landscape Design

Other actions undertaken as a result of the 2002 drought included a GIS linkage of water use at the parcel-level to the Comprehensive Plan designation for each parcel. Doing this allowed staff to project water demands by land use category, which facilitated future Comprehensive Plan updates. Further collaboration between City Planning and Water Resources staff linked the City’s Water Supply Plan with the water demand projections, resulting in a dynamic system that can be used for planning, estimating water supply gap and rebalancing land use and water supply if needed.

Information Sharing

Direct linkage between the Comprehensive Plan and the Water Supply Plan enabled City staff to present water demand projections to the Westminster City Council, improving the awareness and involvement of the elected decision-makers. The City’s most recent Comprehensive Plan identified new development categories such as vertical mixed-use and traditional neighborhood development, once again requiring planners to work with water resource staff to develop water demand estimates addressing these new categories. Following adoption of the new plan, water demands were recalculated and City staff determined that through conservation and other measures, the plan’s build-out was achievable even accounting for increased densities.

In 2016, the Planning Division instituted a new “Pre-Application” process for development customers. Water resource staff are included to describe the tap fee process and identify concerns with projected water use. Recommendations are made to both reduce tap fee and save water. As one example, through the review process staff identified a tap fee reduction of over $100,000 by using different fixtures in a recent commercial project.

Current Practices

These innovations now allow the City to use the Comprehensive Plan itself as the main vehicle to manage development and water supply. Each land use category has an associated water demand assumption comprised of indoor and outdoor water use in acre-feet. Water demands per land use category are regularly revisited, and most recently an audit of all utility accounts was completed to ensure a data-driven process. Having set categories is particularly critical when changes in land use are proposed; a water supply impact is evaluated in each case and this often becomes the critical discussion for decision makers.

Figure 7. Water Demand By Comp Plan Category

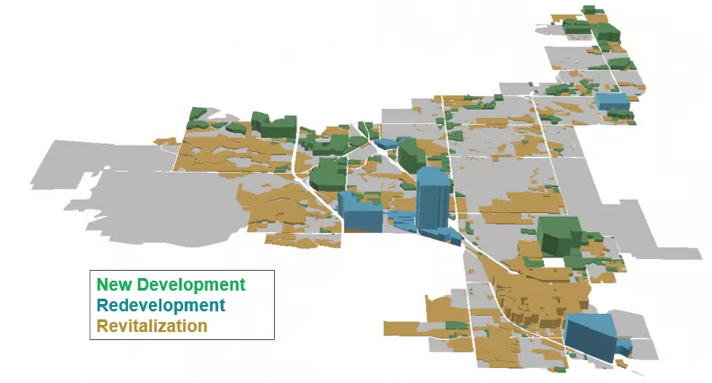

The Plan addresses three primary growth variables:

⦁ New development types: In recent years the City has seen new patterns of development in contrast to the traditional single-family development that characterized growth in earlier decades. Although compact development results in less outdoor water usage, indoor usage may increase when calculated on a per acre basis. This issue bears close attention because outdoor water restrictions buffer overall use when drought restrictions are in effect. Specifically, drought restrictions allow more water to remain within the system, so care must be exercised so as not to over-allocate water for indoor use.

⦁ Redevelopment: Similar to challenges posed by compact development, redevelopment can also increase per-acre water usage. For example, the City’s transit oriented development is located in an area of light industrial uses. The development is planned to include mixed-use buildings up to eight stories in height with up to 1,340 residences over a 20 to 30 year build out. This project is a priority for the City, but given the increase in resources necessary to support the development, strategies to address increased water use were required.

Figure 8. TOD Redevelopment

⦁ Revitalization: Following Westminster’s recovery from the Great Recession, the City had older neighborhoods primed for revitalization. As many of these well-located neighborhoods were brought to market, owners were making improvements such as refreshed landscaping, irrigation, and, especially for smaller homes, expanded kitchens and adding bathrooms. These changes have the potential to affect water use habits and need to be accounted for in demand calculations.

Figure 9. 3-D Allocation of Water Supply

As of the time of the this article, the Comprehensive Plan and Water Supply Plan are undergoing further updates through scenario planning exercises to consider the types of development expected on the remaining land inventory, variations in water use habits and differing climate scenarios. As with the goals identified decades ago, the desire is to promote a reliable and safe water supply, manage growth, and adapt to changing needs.

As described in this article, land use and water supply planning is an ongoing challenge. Even as improvements are achieved, monitoring and refinement must be done to address patterns of growth, water usage habits and infrastructure coordination. Supporting the type of inter-disciplinary problem-solving described here requires the identification of stakeholders and teambuilding – to include the water provider(s), City or County staff including planning, water resources and engineers; elected officials; the development community; citizens and rate-payers. Moreover, the team must be similarly informed, aligned toward common goals and meet regularly. Develop projects cooperatively so there is a sense of ownership across disciplines – avoid silos! And finally, integrate water and the infrastructure system into the Comprehensive Plan.

Figure 10. Land Use/Water Supply Planning Cycle

Andrew Spurgin, AICP is Principal Planner over long range planning for City of Westminster, Colorado. He has 22 years of experience in development review, long-range planning and environmental management in the Southwest – with work experience in Arizona, California and Texas. His current work in Westminster builds upon previous efforts to integrate land use and water planning as the City transitions from a suburban to an urban community in the fast growing Denver-Boulder corridor.